I wrote a little about Uniontown’ history in my last post about the National Road. This week, I continue with some detail about Uniontown’s architecture and its historic heroes.

Uniontown’s Architectural Gems

Uniontown’s loveliest building is the Beaux-Arts State Theater Center for the Arts. Designed in 1921 by prominent theater architect Thomas Lamb, it opened on October 30, 1922 to acclaim as the “largest, finest and most beautiful playhouse in Pennsylvania.”

Originally hosting vaudeville shows and silent films, the theater also showcased nationally-popular big bands like Paul Whiteman, Glen Gray, and the Dorsey Brothers in the 1940s. Like so many grand theaters, it lost much of its audience in the declining mill town and closed in 1973. The theater was purchase in 1988 by the Greater Uniontown Heritage Consortium. Today it presents everything from classic films to local dance recitals.

Here’s a gallery of some of the other little gems that we discovered on our walk through downtown Uniontown.

But, to my surprise, what impressed me the most about Uniontown was its history of heroism, and its commendable civic habit or honoring heroes.

Uniontown hero: General George Marshall

Uniontown’s best known local hero is General George Marshall. Marshall was born on December 31, 1880 and raised in Uniontown, where he was known by the nickname “Flicker.” Marshall’s father was a well-to-do coal magnate, who sold his mining business to invest in real estate. He lost enough of his money that the family begged food from a local hotel for a while.

Although he was a notoriously poor student, young George somehow managed to be admitted to Virginia Military Institute. There, his poor academic performance continued. But he thrived under the military discipline and a moral culture dedicated to service, chivalric courtesy, self-control and integrity. The young cadets were taught to emulate great men like George Washington and Pericles.

Marshall took his moral lessons to heart. He became so tough and self-disciplined that he once was injured early in a football game and nevertheless played the entire game.

Under the discipline at VMI, Marshall became fanatical about neatness, organization and attention to detail. This stood him in good stead in his military career, as he gained a reputation as an ace at logistics, planning and administration. These organization skills made him so valuable to his superiors that in World War One he never saw the combat that he deeply desired, although he was often at the front lines observing and reporting.

Marshall had a strong commitment to the Army, but he wasn’t necessarily a traditionalist. One the eve of World War Two, Roosevelt placed him in charge of Infantry School at Fort Benning. There, Marshall shook up the old-fashioned methods of training officers to lead troops in battle. Many of the most important officers to serve in WWII were trained under Marshall’s revised methods. He trained his officers to think or their feet and taught the maxim that a mediocre decision taken in time is better than a perfect decision that comes too late.

The Marshall Plan

Marshall was FDR’s Chief of Staff during most of WWII, and served as ambassador to Chine from 1945-47. But he is best known for the war recovery plan that he developed for Europe in 1947, known to history as The Marshall Plan. Between 1948 and 1952, the United States allocated over $17 billion ($130B in today’s dollars) to the economic recovery of war-devastated Western Europe. The Plan saved thousands of Europeans from starvation, allowed the end of rationing and reduced the influence of Communist parties in Western Europe. It was a precursor to NATO, the European Economic Community, the Bretton-Woods international monetary agreement and the European Union.

The Marshall Plan offered help to the USSR and the eastern bloc countries, too, but they turned it down. Seems like a bad decision. When the Marshall Plan began, per capita Gross Domestic Product in both the east and the west was $2000. By 1990, Western Europe boasted a per capita GDP of $20,000. The comparable figure in the East was only $9000.

A fine statue of Marshall stands in a little square in downtown Uniontown, honoring a man who started as a poor student in Uniontown and ended up changing the world.

Uniontown heroes: The 1894 coal mine strikers

I wrote in my previous post that coal mining was one of Uniontown’s main industries in the 1890s. In 1889, 65,723,110 tons of bituminous coal were mined in the United States, employing 300,000 miners and other workers. Nearly half of all naval ships in the world burned for fuel bituminous coal mined in the Appalachian region.

Back in the days before the Federal Reserve and floating currencies, Panics used to periodically hit the financial sector. These Panics then reverberated across the whole economy, and the Panic of 1893 hit coal mining especially hard. Factories reduced or ceased production and fewer trains criss-crossed the country, which reduced demand for coal. The mining companies reduced wages in 1893 and again in 1894. Miners who earned 79 cents per ton of coal in early 1893 were earning between 38 and 60 cents a ton by April of 1894.

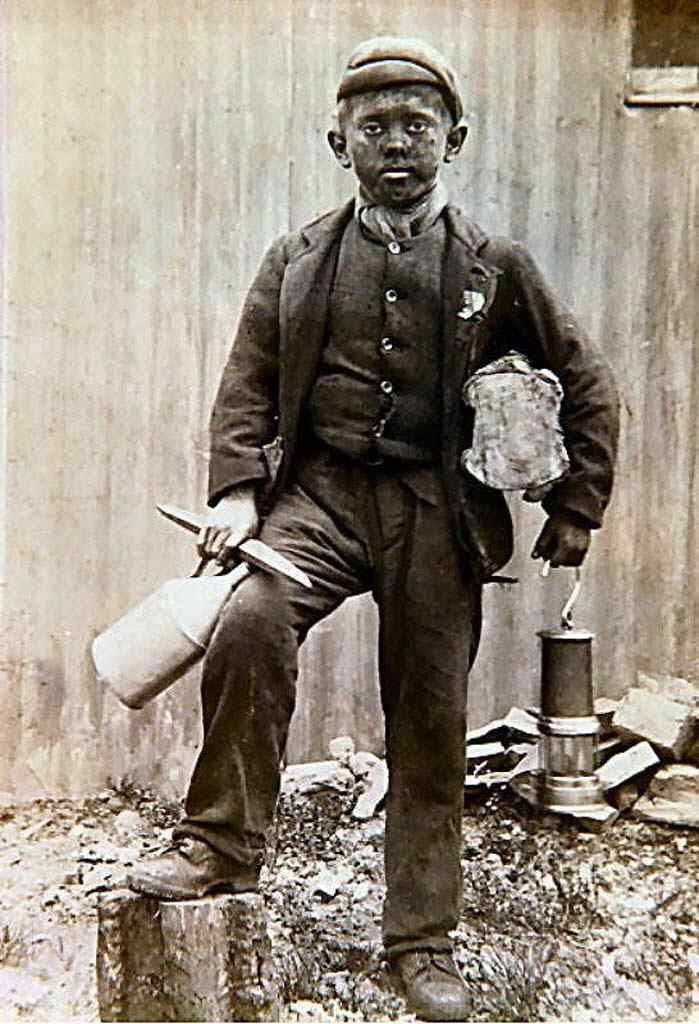

For this paltry wage, the miners worked in dangerous conditions. Mines weren’t mechanized until the early twentieth century, so in the 1890s, the men were still working with pick-axes, hand drills and dynamite. They were susceptible to frequent fatal or crippling accidents and to “miner’s asthma,” what we call today black lung disease. Boys as young as twelve, called breakers, worked sorting coal from rocks, laboring outdoors in all weather. When they turned eighteen, they could go into the mines.

Coal miners were barely making ends meet even before the wage cuts. And, in many coal-mining settlements, they were captive to company stores and company rental property.

One anonymous Pennsylvania miner, telling his story in 1902, reported that he earned $33.52 per month in 1891. His rent was $10 per month, his average monthly bill at the company store was $20, and coal for his furnace cost $4 per month. So, the average miner was constantly in debt. When his wife was sick for eleven weeks in 1896, the doctor’s bill was $20 and medicine cost $18. He didn’t say where he conjured up the money from. One imagines the passing of a hat, the 1890s version of Go Fund Me.

The 1894 Strike

So, the wage reductions left the miners truly desperate. The United Mine Workers was a new organization at the time. They had only thirteen thousand members and only $2600 in their treasury. Nevertheless, they called a strike, demanding a return to the wages that prevailed on May 1, 1893.

More than 180,000 miners in Colorado, Illinois, Ohio, West Virginia and Pennsylvania went on strike on April 21, 1894. Most of them weren’t dues-paying members of the UMW; they were just desperate men.

On May 23 in Uniontown, the strike turned violent. Fifteen guards with carbines and machine guns opened fire to hold off an attack by 1500 striking miners killing five and wounding eight.

Meanwhile, the mine owners, squeezed between their workers, their freight costs, their bankers and their own desire for profit, refused to budge.

Five families buried a husband, father or son, and the miners went back to work in late June at the 1894 wage level. But more strikes followed, with another major one in 1933. Today, coal mining is still a dangerous job, but it is much safer than it was in the 1890s, and much better renumerated, thanks to a union movement that was born of desperation and courage in the 1890s.

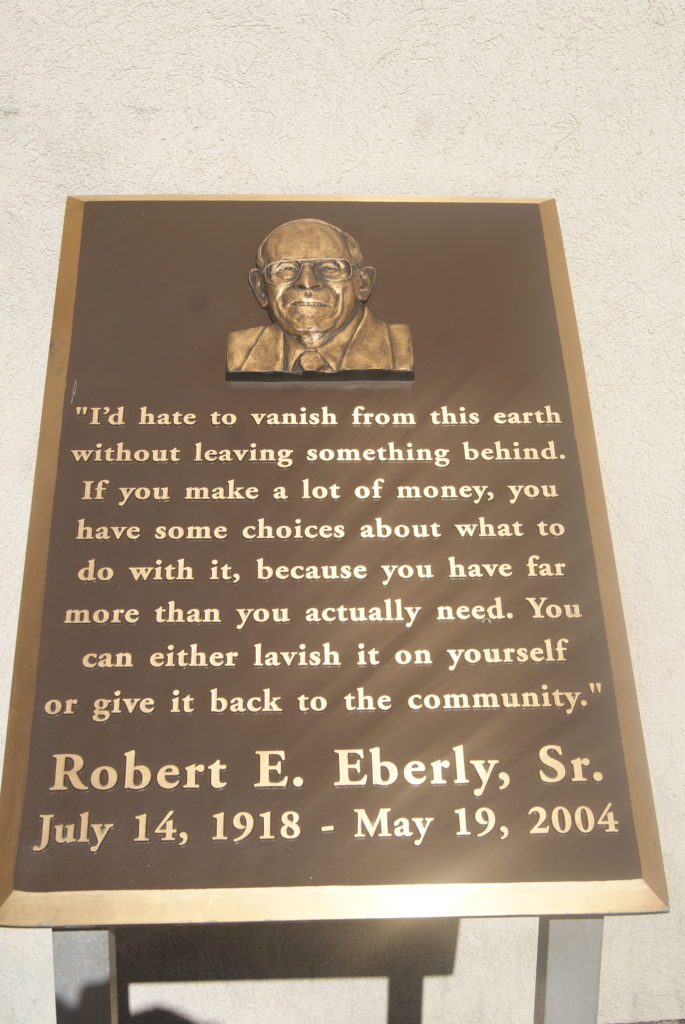

And Other Local Heroes

Sources

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bituminous_coal_miners%27_strike_of_1894

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_coal_miners#Coal_mining_in_the_19th_century

https://ehistory.osu.edu/exhibitions/gildedage/content/MinersStory

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marshall_Plan

Brooks, David. The Road to Character. New York; Random House, 2015.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marshall_Plan