The Old National Road is the gift that keeps on giving. This summer, Al and I realized that we’d given the Maryland section of the road short shrift, and we decided to return and do it justice.

Nemacolin

The section of National Road between Cumberland, MD, and Brownsville, PA, is also called Nemacolin’s Path or Nemacolin’s Trail. I was especially curious about Nemacolin’s contribution, because of my recent interest in the original natives of our area.

Nemacolin, of course, also has a very swanky resort in the Laurel Highlands named after him. He was born in 1715 near Brandywine Creek and a Swedish trading post that later became Fort Christina and, still later, Wilmington, Delaware.

His father was is variously named as either Checochinican or Leni Lenape, a chief of the Fish Clan of the Turtle tribe of the Delaware/Lenape nation.

The Delaware nation originally lived along the Delaware River in New Jersey. They spoke a form of Algonquin and were related to the Miami, Ottawa and Shawnee. The other Algonquin tribes called them “grandfathers” because they believed the Delaware were the most ancient Algonquin tribe. The tribe had moved west as the British encroached on New Jersey and Delaware.

By treaty with William Penn in 1726, the tribe ceded their land on both sides of the Brandywine. Thus, Nemacolin grew up near Shamokin, PA, in a village along the Susquehanna River. The Indians called Shamokin “Schahamokink” (“place of eels”). An Indian tribe called the Saponi had already settled there. The came from North Carolina or Virginia and spoke a Siouan language. Their name may have come from the Siouan word for black: “sapa”. Or it may have come from the name of a female goddess of their religion, Sepy. In the seventeenth century the English explorer John Lederer described them as “governed by an absolute Monarch; the People of a high stature, warlike and rich.”

Nemacolin and the National Road

Nemacolin and his family later moved south and west and lived for a while with the Cresap family. Thomas Cresap was born in 1702 in Skipton, Yorkshire. He later settled as a farmer and trader near Wills Creek in present-day Cumberland.

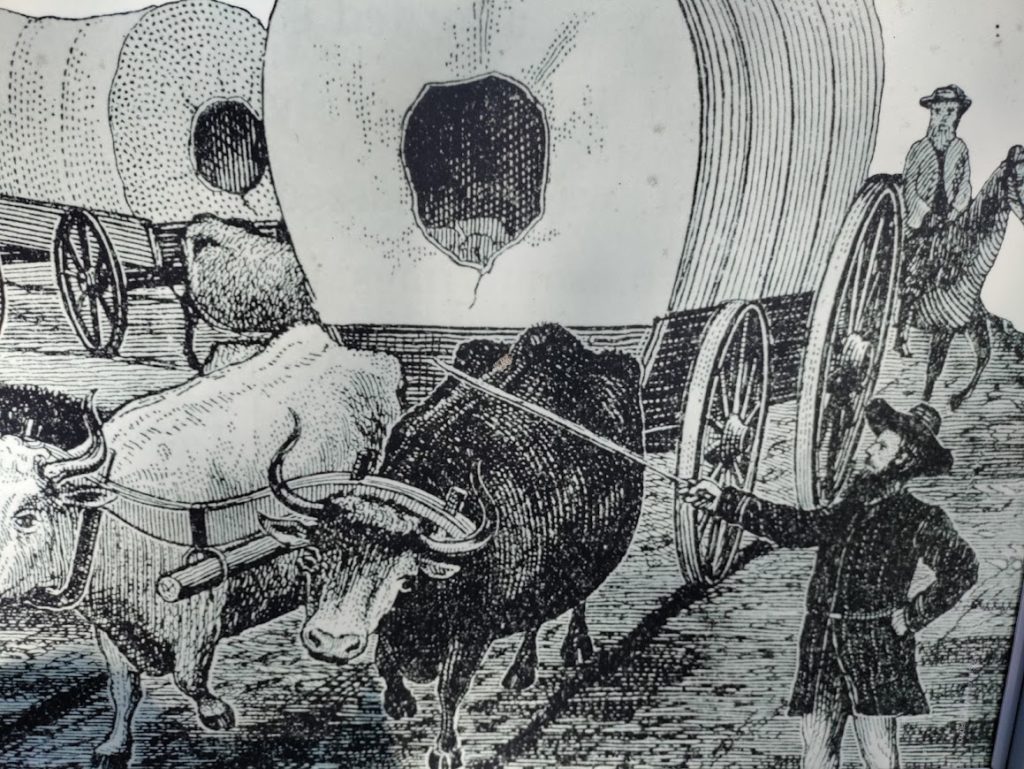

In 1750, Cresap was commissioned to improve the old Indian path through the Cumberland Narrows, across the Appalachian Mountains.

Cresap hired his friend Nemacolin and Nemacolin’s two sons to help with the stretch between Wills Creek and Redstone Creek (present-day Brownsville, PA). Christopher Gist oversaw their work, which crossed harsh, mountainous terrain.

Later during the French & Indian War, Gist led George Washington along the trail, which became part Braddock’s Trail, then Forbes Trail, and finally the National Road.

Nemacolin lived to see the British increasingly encroach on his tribe’s land. The treaty of Easton in 1758 compelled the Delaware to move to the Ohio Territory. There, they fought with the Iroquois and were driven further west. Many lived along the Muskingum River in eastern Ohio, or along the Auglize River in the northwestern part of the state. Similar to Guyasuta’s Mingo, the Delaware tried to stay neutral in the American Revolution.

After the Revolution, the Delaware struggled against more white encroachment in the Ohio territory. They were part of the force defeated by General Anthony Wayne at the Battle of Fallen Timbers. They lost most of their land in the Treaty of Greenville in 1795, and the rest in 1829. Finally, they moved west of the Mississippi River.

Nemacolin eventually moved his tribe to a Shawnee town on Blennerhassett Island in the Ohio River. The island sits on a stretch of the river between West Virginia and Ohio, along Route 50. Nemacolin died there in 1767.

Our Drive Along Nemacolin’s Trail: Cumberland

We began at the official start of the road in Cumberland. Cumberland, Maryland, is a small, pretty city with lots of nineteenth-century architecture and much of historical interest. The people there are very friendly and helpful. When we had trouble locating the site of the National Road’s start, we stopped at a museum to see if we could find information there. The museum was closed, but the County Comptroller’s Office next door was open. The clerk there directed us to the railroad station across the street and told us we could leave our car parked in her office’s free parking lot. At the railroad station, we met a very knowledgeable local who took the time to point us to abundant historical resources. Again and again in our travels, we find people who love their hometowns and are eager to share them.

In addition to the starting point of the National Pike, Cumberland was home to George Washington’s headquarters during the French & Indian War. The building still stands.

The town is also home to both the old C&O Canal and several Civil War sites. We vowed to return and explore those at a future date.

Our Drive Along Nemacolin’s Trail: LaVale Tollhouse and Casselman Bridge

Along the drive to from Cumberland to Brownsville, we also explored another toll house, the LaVale Tollhouse. It looked very much like the ones we’d seen last year. But each toll house is different in what it provides. This one had a very nicely reproduced interior (see photos below). And we learned that the toll collectors were paid $200 per year, in addition to their free lodging in the toll house. The collectors had to be alert, because many people tried to avoid paying the toll. We learned, too, that the LaVale Tollhouse collected almost $10,000 in tolls in its first year of operation.

We also discovered the magnificent Casselman River Bridge, now surrounded by a pretty Maryland state park. This stone arch bridge, dating to 1813, remained in use until the rerouting of Route 40 in 1933. When it was constructed, it was the largest single-span stone arch bridge in the United States. Presidents James Monroe, Andrew Jackson, William Henry Harrison, James Polk, Zachary Taylor, and Abraham Lincoln all crossed this massive, well-maintained stone bridge.

Nemacolin’s Trail ends at Brownsville, which we had visited last year. The improvements to this old Indian Trail between Wills Creek and Redstone Creek mark the true birth of the National Road, sixty years before its official start.

Sources

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nemacolin

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nemacolin%27s_Path

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shamokin,_Pennsylvania

https://www.ancestry.com/genealogy/records/nemacolin-native-american-24-2z6gyhz

https://www.ancestry.com/genealogy/records/nemacolin-native-american-24-2z6gyhz

https://ohiohistorycentral.org/w/Delaware_Indians