The summer before I started ninth grade was the summer when my family was poor. We were poor in a new 3-bedroom ranch house in a tidy little development, so we had to be secretly poor, but we were poor nonetheless. My father had finally drunk himself out of a job and now spent his days drinking Fort Pitt beer in front of TV soap operas, disintegrating in front of our eyes, 40 years old and already gaunt with hairless legs and a patchy scalp. My mother took a job. She was 35, weighed less than 100 pounds, looked younger than I did, and must have seemed out of place in front of her IBM Selectric, a tiny pre-adolescent supporting a family of five.

The summer before I started ninth grade was the summer when my family was poor. We were poor in a new 3-bedroom ranch house in a tidy little development, so we had to be secretly poor, but we were poor nonetheless. My father had finally drunk himself out of a job and now spent his days drinking Fort Pitt beer in front of TV soap operas, disintegrating in front of our eyes, 40 years old and already gaunt with hairless legs and a patchy scalp. My mother took a job. She was 35, weighed less than 100 pounds, looked younger than I did, and must have seemed out of place in front of her IBM Selectric, a tiny pre-adolescent supporting a family of five.

Our radio broke and we didn’t buy a new one. Our ’65 Chevy Bel Air was tempermental. Some mornings, my mother drove to work, other mornings, when the Chevy was in a bad mood, she walked, or called someone for a ride. Towards the end of a pay period, lunch was whatever I could find in the kitchen: graham crackers and dill pickles, chicken noodle soup and powdered milk, saltines with jelly. My younger brother and sister were often invited to lunch at friends’ houses. Dad pretty much stuck with his pal, Fort Pitt.

Patti Ann next door, who had recently graduated from high school and gotten a secretarial job downtown, gave me 2-year-old copies of Glamour and Seventeen, and her cast-off clothing. I pored over the magazines, wishing that I knew boys on whom I could practice “The Art of Flirting” or “How to Get Asked on a Second Date.” I studied the fashions, and ripped apart my own old clothes and Patti Ann’s cast-offs and made myself new clothes: a halter top from the top of a baby-doll dress, shorts from too-short bell-bottoms, a belt from the strap of a handbag.

I spent as much time as I could away from home. Instead of watching the soaps with my father, I watched them at my friend Judy’s house. Judy’s parents were elderly, retired, grim-faced people. They were careful with money and never invited me to stay for a meal, but their house was air-conditioned and Fort-Pitt-free, and Judy’s mother watched the soaps without making alcohol-fueled comments about what she thought the characters would do next.

I had just the right combination of curiosity, worldliness, naivte and luck to get into trouble, but not big trouble. I rode the bus to Oakland and necked on a bench with a college boy that I met just that day on the University of Pittsburgh lawn. I lied and told my parents I had a ride to a dance, and then walked the 3 miles there at 7:00 and the 3 miles home at almost midnight. On my way home, a man exposed himself to me in between two houses. His hairless naked body shone white in the moonlight. I stood in shock for just a split second, like a cartoon character with exclamation points radiating from my head, and then I ran, my coltish 13-year-old legs pumping, wooshing through the summer night air, not stopping until I reached the first busy, well-lit street. I ran right into a girl I knew, older than me, the kind of girl who smoked cigarettes, wore dark eyeliner and made up mean nicknames for sensitive, studious girls like me. In a shaking voice, I told her what I had just seen. Telling a tough girl like Debbie made me feel brave and mature, as if she and I now shared some level of sophistication and dark worldliness. Debbie listened and smoked, and didn’t offer me a cigarette. She squinted through her exhaled smoke and approved of my “getting the hell out of there.” She told me that her boyfriend wanted to have sex with her and that she would never consent to this, even if he got down on his knees and kissed her “rosy red ass.” I felt a sudden, passionate loyalty to her that wouldn’t let me admit to myself that I suspected that she probably would have sex with him, and soon. We were two very different girls who barely knew each other, walking together late on a summer night, sharing secrets. She was the only person I ever told about the flasher, but the next time we saw each other, we didn’t even say hi.

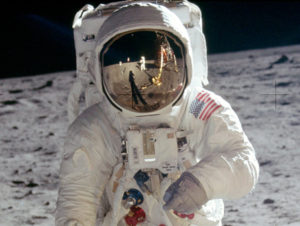

It was the summer of Woodstock, one of nine summers of the Viet Nam war, the summer of the moon landing. I watched Neil Armstrong’s historic steps on my grandparents’ black-and-white TV. The picture was grainy and blurry, Armstrong’s voice staticky. Afterward, my uncle and I went out on the porch and looked up at the moon, a skinny 13-year old and a balding 37-year-old bachelor grad student. Neither of us said anything. We just sat on the porch together for a long time and looked at the moon and thought about people being there for the first time.

My family was poor. I was a skinny, studious girl, neglected by distracted parents and isolated for the summer from most of my school friends. With no radio, I missed all the hit songs of the summer: Hair, Get Back, Grazin’ in the Grass. I never heard the song McArthur Park until 1972. I borrowed books from the library and read lying in front of the fan if my father wasn’t in the living room, and holed up in my hot, stuffy bedroom if he was. I made my own clothes from whatever was at hand. And I daydreamed about a better life, a life that was no less possible, after all, than putting a man on the moon.