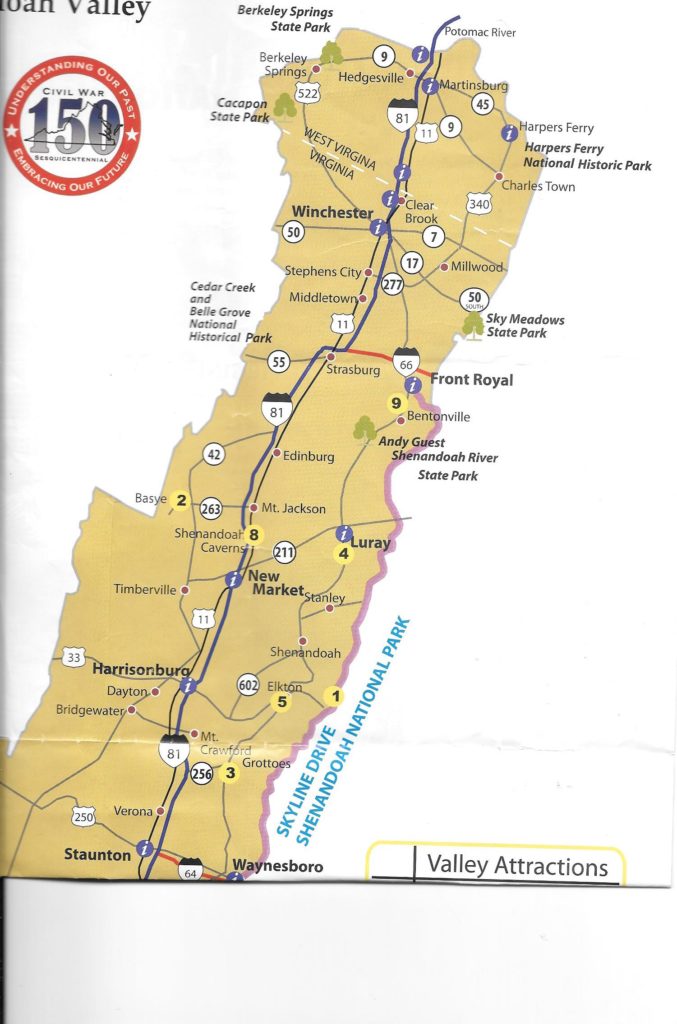

From any of the 75 scenic overlooks along Skyline Drive in Shenandoah National Park, you can view the broad, green expanse of the beautiful Shenandoah Valley. It lies between the Blue Ridge Mountains to the east and the Allegheny Mountains to the west. No more than 25 miles wide at any point, it is peaceful, bucolic and semi-rural. Before the American Civil War, it was Virginia’s breadbasket.

And during the war it was hotly contested.

Encyclopediavirginia.org aptly describes the valley as pointing “dagger-like at the North and especially at Washington, D.C.” And the Union wanted that dagger blunted.

General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson successfully defended the Valley in 1862. And Robert E Lee used it as the jump-off point for his Gettysburg campaign in 1863, using the mountains to screen his army’s movement.

Prelude to the Battle of Cedar Creek

But by 1864, conditions favored the Union. Stonewall Jackson was dead. The Confederates were running out of supplies and the loss of the valley would deprive Lee’s army of a desperately-needed source of grain and livestock. Grant had Lee pinned down near Petersburg. And three years of war had depleted Confederate manpower.

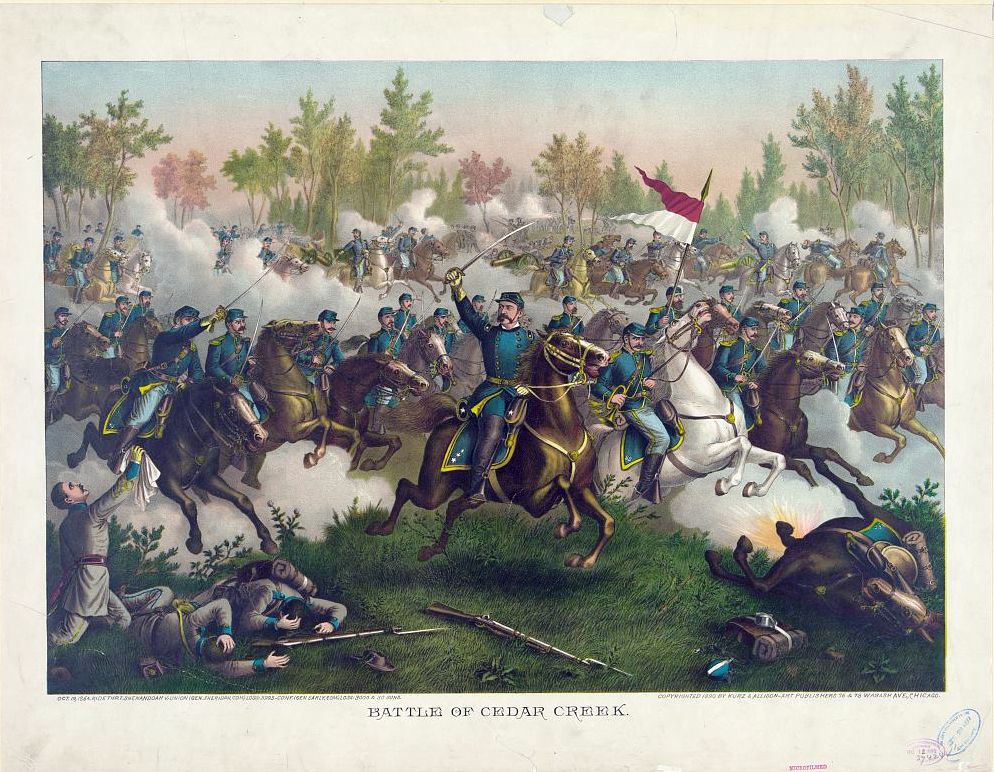

The 1864 Shenandoah Valley campaign was characterized by hubris on both sides. And the Battle of Cedar Creek is particularly interesting because it featured so many surprising twists and turns, all in one day.

In the early summer of 1864, Confederate General Jubal Early conducted raids out of the Shenandoah towards Washington, D.C. He hoped to force Ulysses Grant to divert some of his forces to defend the capital, which would bring some relief to Lee at Petersburg. Instead, Grant decided that it was time to eliminate the pesky Early. He gave the job to General Philip Sheridan, along with orders to pursue Early “to the death.”

Sheridan Surprises Early

Early had some initial success in fending off Union forces and Lee became complacent enough to bring a division back to defend Richmond. So, when Sheridan next attacked, he swept the Rebel army out of Winchester, forcing them to retreat south through the Shenandoah Valley to Waynesboro.

Presaging Sherman’s March to the Sea in the west, Sheridan executed a scorched-earth campaign through the valley to deprive the Confederate army of desperately-needed food. Following Grant’s order that he make the valley “so desolate that crows flying over it would have to carry their own provender,” Sheridan slaughtered sheep, hogs and cattle, and claimed to have put the torch to 2000 barns and over 70 mills.

But now it was Sheridan’s turn to become over-confident. Convinced that he had sufficiently weakened his opponent, Sheridan sent a whole corps back to Petersburg. He established his headquarters at Cedar Creek, and left for a meeting in Washington.

Sheridan had some reason for complacency. His troops were well-positioned behind Cedar Creek near Belle Grove Plantation, and they outnumbered the Confederate forces. But the Rebels knew the terrain. And General John Gordon took a look from one of the mountaintops and thought he saw a small chance to surprise their opponents.

Early Turns the Tables

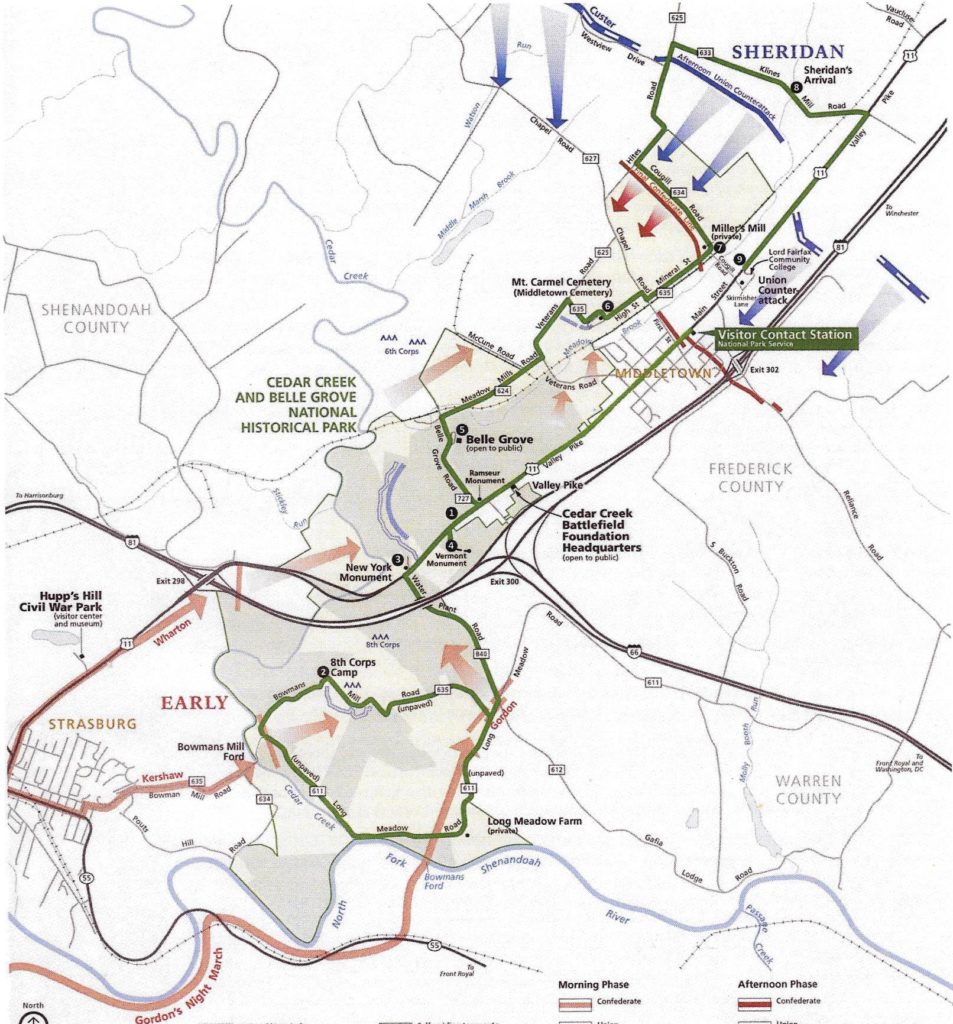

Everything had to work perfectly. Without the benefit of modern communications, three columns of Rebel infantry and two cavalry brigades had to converge on the Union flank at the same time, crossing both Cedar Creek and the Shenandoah River, and travelling by night. Against all odds and aided by heavy fog, the Rebels completely surprised the Union Army of West Virginia, including a division commanded by future president Rutherford B. Hayes. Future business magnate Henry DuPont received a Medal of Honor after the battle, for stalling the Confederate advance with his artillery, and saving nine of his sixteen cannons. But is wasn’t anything close to enough.

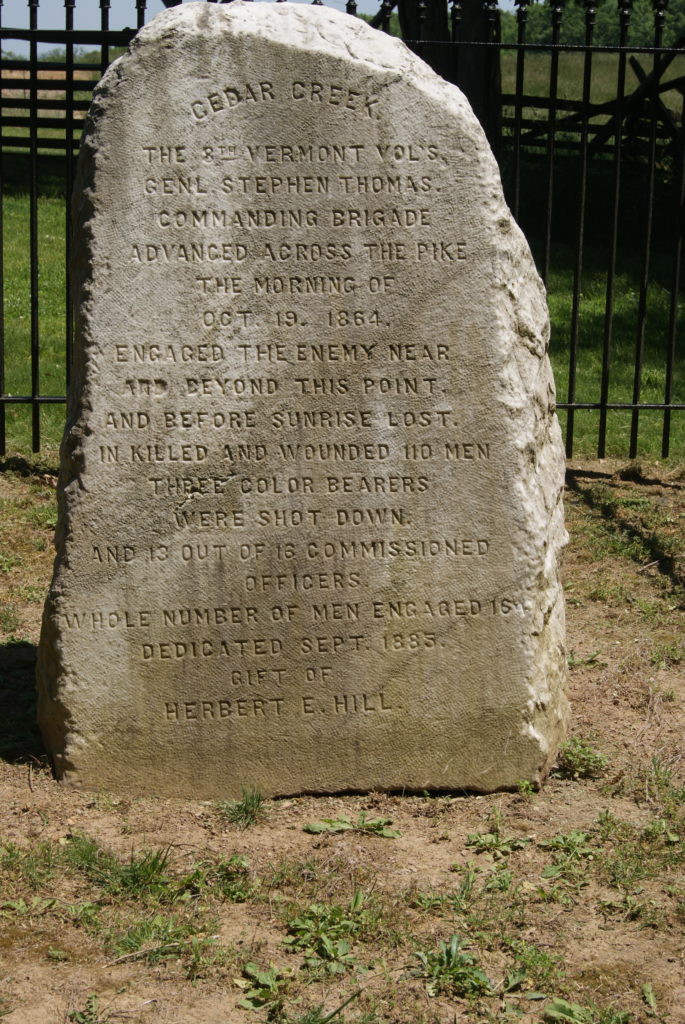

Union General William Emory ordered a brigade into the fighting to slow down the Rebels. To me, this is the most poignant moment of the battle. A brigade of no more than 1000 men from Vermont, New York, Pennsylvania, and Connecticut is sent towards the battle line to hold off the enemy until a larger force can form a new line. They must have known that they would take heavy casualties. As the Vermonters at the front of the skirmish line moved forward, retreating forces rushed past them in the other direction.

One Vermonter described the moment when they met the Confederates at dawn in the fog-shrouded woods:

“One of the most desperate and ugly hand-to-hand conflicts over the flag that has ever been recorded…Men seemed more like demons than human beings, as they struck fiercely at each other with clubbed musket and bayonet.”

Of the 165 Vermont men who fought, 110 we killed or wounded. The 47th Pennsylvania suffered 40 killed and 134 wounded out of 300 men. But they had bought precious time – and help was on the way.

The Tables Turn Again

Sheridan had spent the night In Winchester on his way home from Washington. He heard reports as early as 6 a.m. of sounds of artillery coming from the south. But he didn’t round up his cavalry and start riding south until 9 a.m. By the time he reached the battlefield around 10:30, the Union had retreated and begun to form a new defensive line.

It was the Confederates’ turn to be complacent again. Early had thoroughly routed his enemy and failed to pursue. The Rebel troops focused on plundering some much-needed supplies. This is another poignant moment. The Rebel soldiers, barefoot and hungry, cold and wet from their march, come across a bounty. Blankets and uniforms. Boots! Food! And 24 captured union artillery pieces. But they weren’t counting on Sheridan. The Union general immediately began organizing a counter-attack and swore that he would make coffee from Cedar Creek by evening.

At 4:00 the Union began their attack. One of the day’s heroes was General George Armstrong Custer, whose cavalry hit the Rebels hard. By 5:00, there was no more Confederate army in the Shenandoah Valley.

Total Union casualties for the day numbered 5665, against 2910 Confederate casualties. But those were men that the South could ill afford to lose. The North would control the Shenandoah Valley for the rest of the war. And Appomattox was only six months in the future.

NOTE: If you want to drive the battlefield, the National Park Service offers a guided tour that can be downloaded to your phone HERE. Also worth a visit is the Cedar Creek Battlefield Foundation headquarters, located at 8437 Valley Pike in Middletown, VA. They have a very nice selection of art and books about the battle and the Civil War in general, as well as gift items made by local crafters. They were closed for remodeling when we stopped, but they let us in to look around anyway and were very helpful in directing us to the NPS guided tour download.

Sources:

https://www.nps.gov/cebe/planyourvisit/self-guided-driving-tour-brochure.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Cedar_Creek