Six years later…

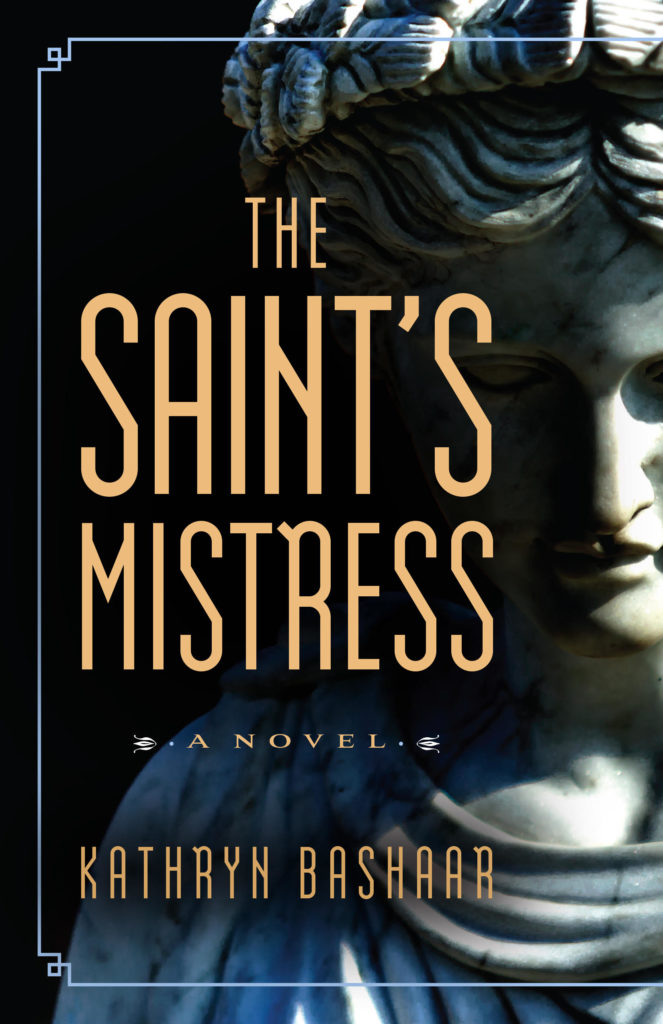

SynergEbooks, a very small publisher, published my first novel in in 2014 as an e-book. The publication and marketing journey was rough and winding, with many twists and turns. I had lots of fun giving author talks in various local libraries, and meeting with reading groups who had selected my novel. In 2016, the book came out in print, and, last year, CamCat publishing bought SynergE. CamCat is re-releasing The Saint’s Mistress later this month with a new cover, improved editing, and some nice art work.

As part of the marketing effort for the re-release, I’m re-blogging some posts from 2014-15. I’ll develop some new material, too. Here’s Part One of a two-part post, describing how I wrote the book. These posts became the basis for my author talks at libraries.

How I got the idea for my first novel

I came to write The Saint’s Mistress via a trail of books.

At the library one April night in 2006, a book called The Well-Educated Mind caught my eye. The Well-Educated Mind recommended Saint Augustine’s Confessions as the first example of a modern autobiography. That intrigued me, but I was a little daunted by the prospect of a book written in the 5th century by an early Father of the Church.

A few months later, again at the library, I noticed a short biography of Augustine by Garry Wills. I remembered my interest in the Confessions and thought this short, modern book might be a way to ease myself into Augustine. In the Wills book, I first discovered Leona – or, more accurately, the faint, ancient scent of her.

Wills wrote a little of Augustine’s beloved, whom he mentions briefly, but never names, in his Confessions. I learned that this unnamed woman had been Augustine’s mistress of many years, and that they had had a child together who died as a young man. Wow, I thought, what must her life have been like? Then: Hmmmm, what WOULD it have been like? And so a flame was lit.

So many reasons NOT to write this book…

The wonderful thing about Leona is that history knows nothing about her, other than what little I learned from Wills. She was Augustine’s mistress. They are believed to have met in Carthage. They had a son. The son died. After that, history is absolutely silent. I could make up anything I wanted, including her name. My only constraints were the historically established facts of Augustine’s life and 4th-5th century Christianity.

I was an amateur, sporadically published, writer of short stories, travel articles and essays. I had finished one novel that I wasn’t quite satisfied with and had no idea how to submit for publication anyway. And I had no experience with historical research. My life also included a demanding full-time job, a husband, a son in college, and a daughter and baby grandson who had just moved back in with us. So, of course, I had to write this book….TO BE CONTINUED

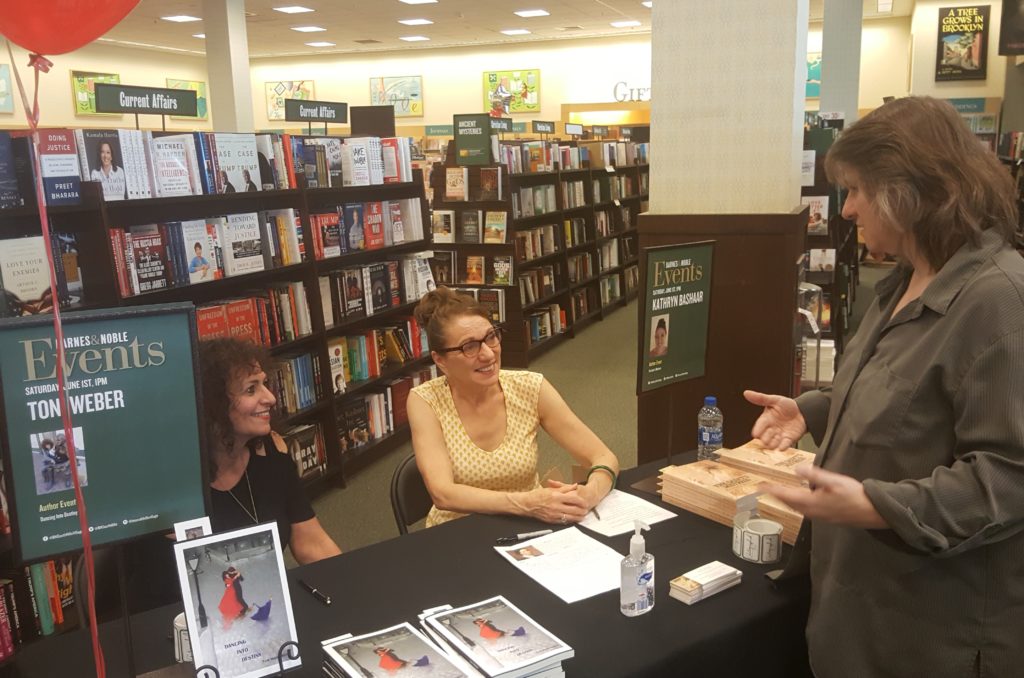

Here are some images from some of my author talks and book festivals. One of the best parts of being an author is meeting other people who love books!

Barnes & Noble

Brentwood Library

Oakmont Library

Shaler North Hills Library

Art & Inspiration at Shaler North Hills

When we say something is Manichean, or someone has a Manichean view, we mean “black and white,” a very sharp distinction between good and evil, with no gray area. But where does the term Manichean come from?

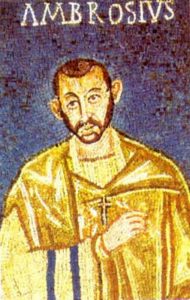

When we say something is Manichean, or someone has a Manichean view, we mean “black and white,” a very sharp distinction between good and evil, with no gray area. But where does the term Manichean come from? Do you enjoy singing hymns in church? Then thank Saint Ambrose; he is generally credited with introducing hymnody into the Western church from the East. And that was only one of his many accomplishments.

Do you enjoy singing hymns in church? Then thank Saint Ambrose; he is generally credited with introducing hymnody into the Western church from the East. And that was only one of his many accomplishments.