I’ve written before about how much the people of the Ancient World were like us. One of my more surprising discoveries, in researching The Saint’s Mistress, was that they had fast food. There was a good reason for this: many apartments, particularly in the poor areas of the cities, lacked kitchens. So, small stands selling quick foods thrived, serving lentils, porridge, bread, sausages, poultry, even an ancient forerunner of pizza! They didn’t have Styrofoam containers, of course. The fast-food meal of the Ancient citizen of Rome or Carthage or Hippo would have been provided in cheap clay pottery, which ended up in massive landfills not so different from our own.

I’ve written before about how much the people of the Ancient World were like us. One of my more surprising discoveries, in researching The Saint’s Mistress, was that they had fast food. There was a good reason for this: many apartments, particularly in the poor areas of the cities, lacked kitchens. So, small stands selling quick foods thrived, serving lentils, porridge, bread, sausages, poultry, even an ancient forerunner of pizza! They didn’t have Styrofoam containers, of course. The fast-food meal of the Ancient citizen of Rome or Carthage or Hippo would have been provided in cheap clay pottery, which ended up in massive landfills not so different from our own.

The first two meals of the day, what we call breakfast and lunch, would have been quick and simple for most people: bread and cheese, perhaps some fruit or a little cold meat, some watered-down wine.

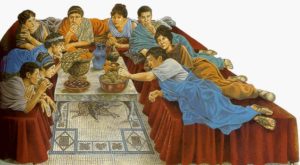

Dinner was eaten in the late afternoon, after a visit to the public baths, and would have been more substantial. Wealthier people in the Roman Empire did eat reclining on cushions, just as they are portrayed. Only children sat. Forks were unknown; they ate with knives, toothpicks, spoons – and their fingers, which entailed a lot of hand-washing between courses.

Ancient Romans of the upper or upper middle class would have had access to many of the same foods familiar to us today. Their fresh fruits and vegetables would have included grapes, figs, apples, leeks, asparagus, beets, gourds and lettuce. An evening meal might include one or more servings of protein: pork, eggs, fish and shellfish, goat meat, and various kinds of poultry. The rich could afford roasted boar or peacock. Those Mediterranean staples, olives and wine, would have been served with every meal.

The poor had to satisfy themselves with the same food for dinner that they had at breakfast time: bread, porridge, perhaps some fruit or cheese

Augustine and his contemporaries would have known many of the same spices and flavorings the we use, such as pepper, cinnamon, and anise.

Honey was their only sweetener, so beekeeping was big business. Hives were tall and domed, made of bark and dried dung, or willow reeds tightly woven and daubed with mud and leaves. Honey was harvested twice a year. The right time in spring was whenever the Pleiades were visible. If the bees who made the honey had fed on poisonous plants like mountain laurel, the honey was poison, causing madness or even death due to heart failure or nervous system collapse.

In The Saint’s Mistress, I portray Augustine’s friend Nebridius as being especially fond of garum. Garum was a sauce that was popular throughout the Roman Empire. There were probably many variations, but it is believed to have been made from fish entrails, blood, salt and spices, and fermented for 20-30 days. My sources said it probably tasted like Worcestershire sauce.

The biggest difference between how we eat and how Saint Augustine and has contemporaries ate, is the amount of labor that it took to produce food. North Africa was the breadbasket of the Roman Empire in Augustine’s time and large-scale, corporate-style farms, like our modern ones, were not unknown. The difference was that ancient farms relied on human and animal labor, rather than on combustion-engine machinery. Food was therefore more expensive, relative to the average income, than it is for us today. Surrounded by abundance, peasants and the urban poor nevertheless knew periods of hunger and even famine.