Check out my post on da AL’s blog: https://happinessbetweentails.com/2020/08/12/whats-a-writer-plus-kathryn-bashaars-review-of-grace/

Category Archives: Blog

David Bradford, Whiskey Rebellion Leader

In rural Pennsylvania, resistance to high taxes and heavy-handed government drives political partisanship and mistrust of elites in the big cities. A description of early 21st-century politics? Well, yes, but it’s a description that has a long history in our state. I’m talking about the Whiskey Rebellion.

I promise that I will write a blog post on the Rebellion itself, soon. But as research the subject, I keep coming across colorful characters whose stories I feel I must tell before treating the Rebellion as a whole. My subject today is David Bradford: lawyer, big-time land-owner, conspirator, Revolutionary War general under Washington, and friend of the Marquis de Lafayette. Yes, another one. I’m starting to think there was hardly a landed gentleman anywhere in Pennsylvania who didn’t know the (apparently super-friendly) Marquis.

David Bradford comes to Western Pennsylvania

For decades, the colonies/states of Pennsylvania and Virginia had disputed their borders in the west. Finally, in 1781, Mason and Dixon drew their famous survey line in favor of Pennsylvania. That same year, David Bradford arrived in Washington County. Bradford was born in Elizabethtown, NJ, and raised in Maryland, but he had family connections in southwestern Pennsylvania. His family were founders of the academy that later became Washington & Jefferson College, and his sisters married prominent local attorneys. Bradford gained admittance to the bar and, by 1783, became Deputy Attorney General for Washington County.

He served in both the Pennsylvania and Virginia General Assemblies, by virtue of being a landowner in both states, In 1788, he married Elizabeth Porter and that same year built one of the first stone houses west of the Allegheny Mountains. More about the house later. Interestingly, he bought four slaves in 1789, but freed them in 1793. More about Bradford and slavery later, too.

The Whiskey Rebellion

Call me crazy, but, so far, Bradford’s life story sounds to me like he was a guy who would definitely not be rocking any boats – let alone escaping in one. He doesn’t sound like someone who would lead a rebellion and become a fugitive from justice.

But David Bradford was an independent thinker. In the early 1790’s, he increasingly disapproved of the centralized-government approach of Washington, Hamilton and the other Federalists. Of particular concern in southwestern Pennsylvania was the excise tax on whiskey. Congress approved the tax on March 3, 1791, and by 1794 several Pennsylvania counties were in full-blown rebellion.

Bradford whole-heartedly agreed with the rebellion and assumed leadership of the insurrection in Washington County. In early August of 1794, he led a militia of 5-7000 men on a march to Pittsburgh to protest the tax.

That had President Washington gnashing his wooden teeth. Washington ordered a federal militia to the west to put down the rebellion, and led the troops himself as far as Bedford, PA.

Bradford’s escape

Legend has it that Bradford escaped out a back window of his house mere minutes before Alexander Hamilton knocked at his door to arrest him. He galloped by horse to McKees Rocks, where he set off down the Ohio River by boat, firing shots at his federal pursuers on the shore.

The real story is both more boring and more interesting. Bradford made his way rather leisurely to Pittsburgh on the advice of friends,. He sailed down the Ohio from there, completely unmolested by federal troops, who apparently had no interest in inflaming the situation by arresting a prominent local attorney and former member of the Pennsylvania General Assembly.

Bradford’s departure may not even have been motivated by imminent arrest. Around the same time as the rebellion, Bradford had argued a case that an enslaved Washington man ought to be freed because his owner had failed to properly register him. He won the case and the embittered slave-owner threatened him with death.

Regardless of his motivations, Bradford escaped the justice of the young U.S. government by re-settling in Spanish Louisiana. In 1797, he completed construction of a new home, which he originally named Laurel Grove and is now called The Myrtles Plantation. It is reputed to be haunted; if you’re interested in that sort of thing, read more HERE. Once the house was completed, he brought his wife and their five children from Pennsylvania to Louisiana, where he and Elizabeth had five more children.

Bradford’s later life

Elizabeth Bradford repeatedly petitioned George Washington to pardon her husband. But Bradford remained a fugitive from justice until 1799, when President John Adams issued a pardon. Meanwhile, though, Bradfod prospered in Spanish Louisiana. By the time he died of yellow fever in 1807, he owned 1050 acres in Louisiana, 3155 in Pennsylvania, 4282 in Virginia, 2000 in Kentucky and 9000 in Ohio. Apparently, a little boat-rocking doesn’t do much damage to land-rich lawyers!

In the early 1800s, Bradford sold the stone house on Main Street in Washington, PA, but it still stands. After stints as a general store, a furniture store and home to the 19th-century American Realist novelist Rebecca Blaine Harding Davis, the house was beautifully restored in the 1960s and named an historic landmark.

The David Bradford House: a Whiskey Rebellion site

Bradford house exterior

Parlor

Dining room

Al and I had a delightful time touring the house and gardens last week. The log cabin in back of the house is not the original log cabin where Bradford conducted his law business, but it is an 18th-century Washington log cabin moved from elsewhere. Our tour guide, Laney Seirsdale, was friendly, enthusiastic and very knowledgeable, and shared with us many tidbits of information about Bradford, the house, and life in late-18th-century Pennsylvania. And the tour cost only $5! Afterward, we had a very nice lunch at a bakery/café down the street Chicco Ballacco. I’m become kind of a connoisseur of iced chai lattes during this overheated summer, and theirs is among the best.

The Bradford House is located at 175 S. Main St., Washington, PA.

Stay tuned for my post on the Whiskey Rebellion. It’s coming, I promise! Meantime, in case you missed it, here’s a link to my previous post on Albert Gallatin.

Sources

Bradford House Historical Association; The Bradford House: A National Historic Landmark; Washington, PA; 2015

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Whiskey_Rebellion

http://www.maptherebellion.com/neatline/show/the-whiskey-rebellion#records/10

Albert Gallatin

“Immigrants: they get the job done”

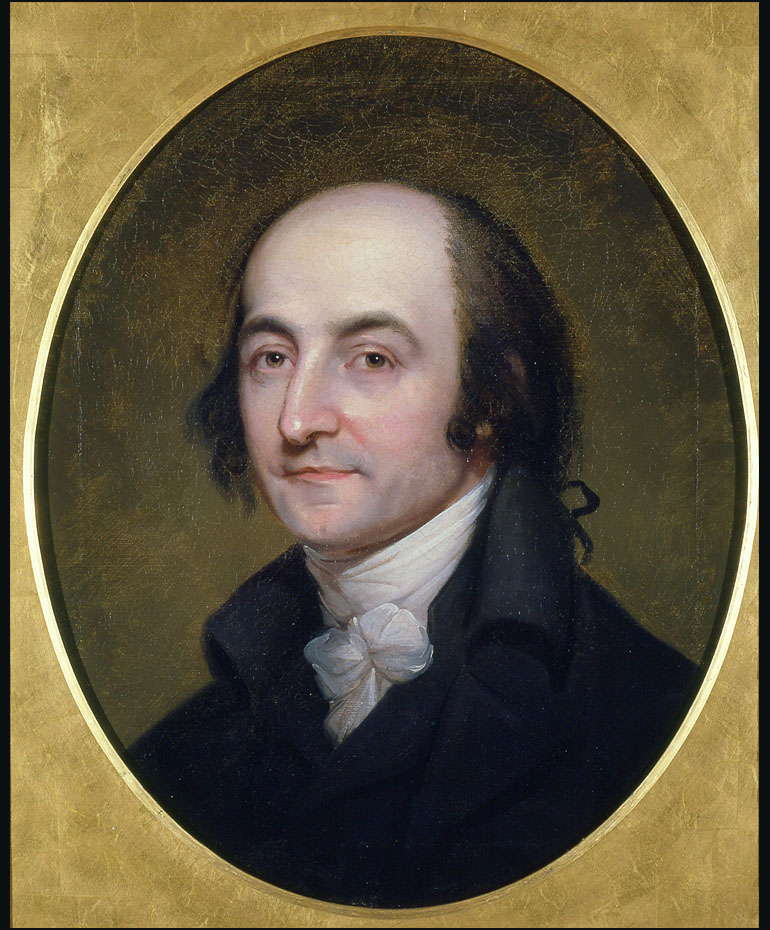

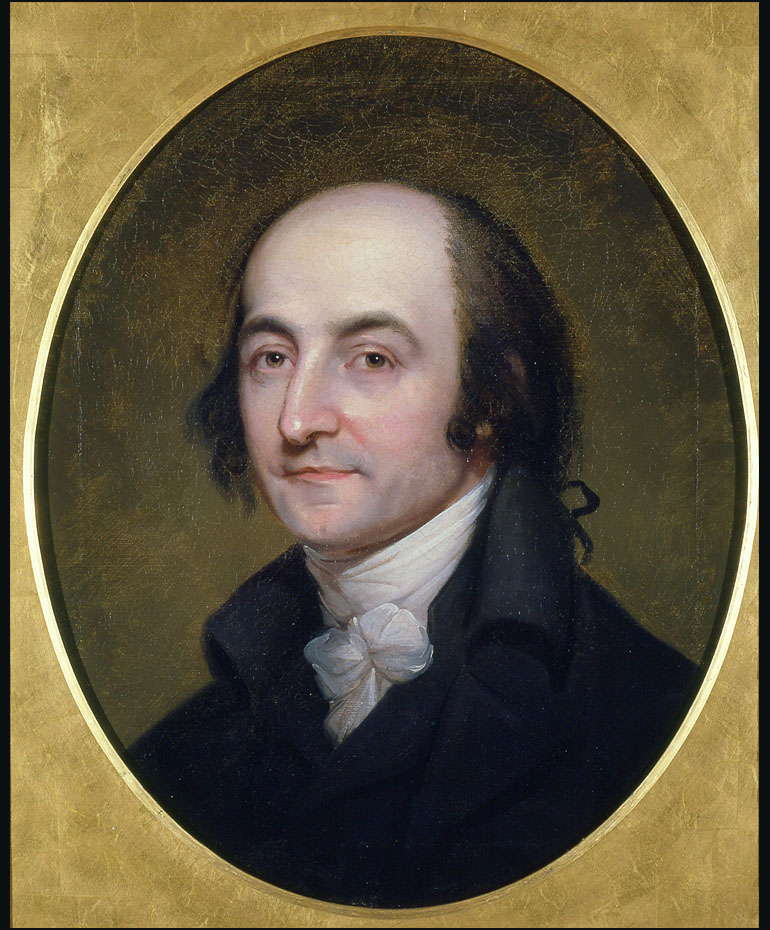

Albert Gallatin

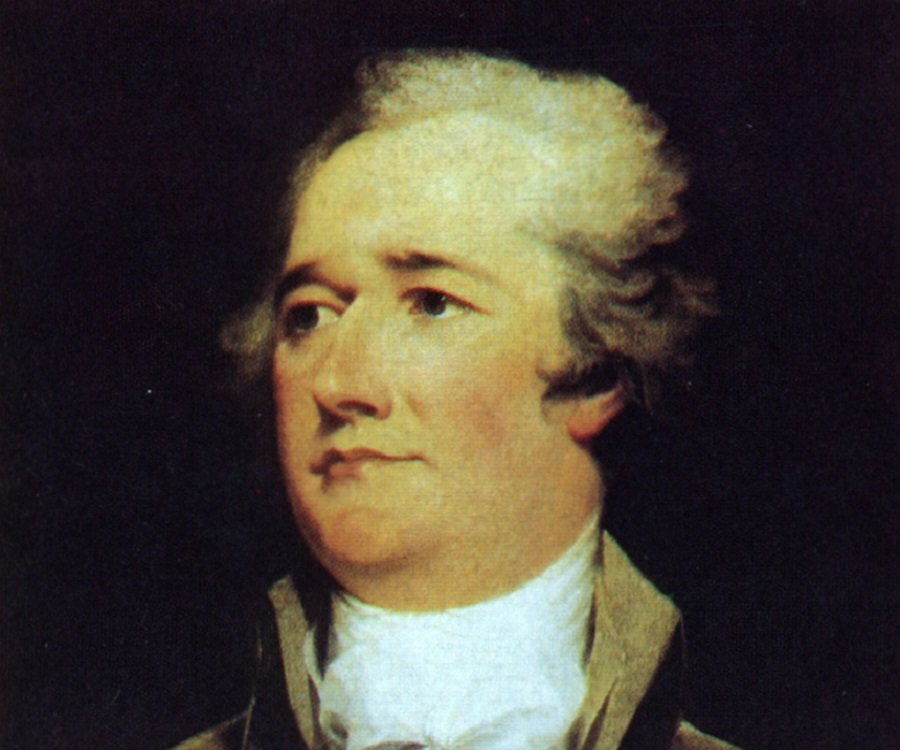

Alexander Hamilton

These two guys had a lot in common, but they would soon be enemies

He was an orphaned immigrant who made good in the young United States, becoming Secretary of the Treasury and founding a bank. He was an early abolitionist, an advisor to George Washington, and a friend of the Marquis de LaFayette. No, I’m not talking about the toast of 21st-century Broadway, Alexander Hamilton. I’m talking about Albert Gallatin.

Gallatin’s career included three terms in the U.S. Congress and 13 years as Treasury secretary under both Jefferson and Madison. He helped negotiate the Treaty of Ghent and served as minister to both France and England. Yet – similar to Hamilton before the Chernow biography and the hit Broadway musical – Gallatin doesn’t get the recognition he deserves. A quick Amazon search for books about Gallatin gave me 26 results, a more respectable number than I expected. A search for books about Hamilton gave me 100 results before I stopped scrolling. That’s counting coloring books, children’s books and books about his wife, Eliza Schuyler, and her sisters, but not counting wall calendars, sketch books, blank books and something called 499 Facts About Hip Hop Hamilton.

Like pre-Chernow Hamilton, Gallatin deserves to be more famous than he is.

Gallatin’s early life

Abraham Alphonse Albert Gallatin was born in Geneva, Switzerland, on January 29, 1761. By 1770, his parents had died, but they left a substantial estate and a relative made sure that Albert received an excellent education. At age 18, Albert set off for the New World with a friend and business partner, Henri Serre. The two young men had the notion of setting themselves up in business in Boston, but their inability to speak English was an impediment.

After a business failure and a stint as a French tutor at Harvard, Gallatin and a new partner, Jean Savary, headed to the western frontier as surveyors. Young Albert fell in love with the Monongahela Valley in southwestern Pennsylvania, and, when he received his inheritance in 1786, he bought 370-3/4 acres in present-day Fayette County, which he named Friendship Hill.

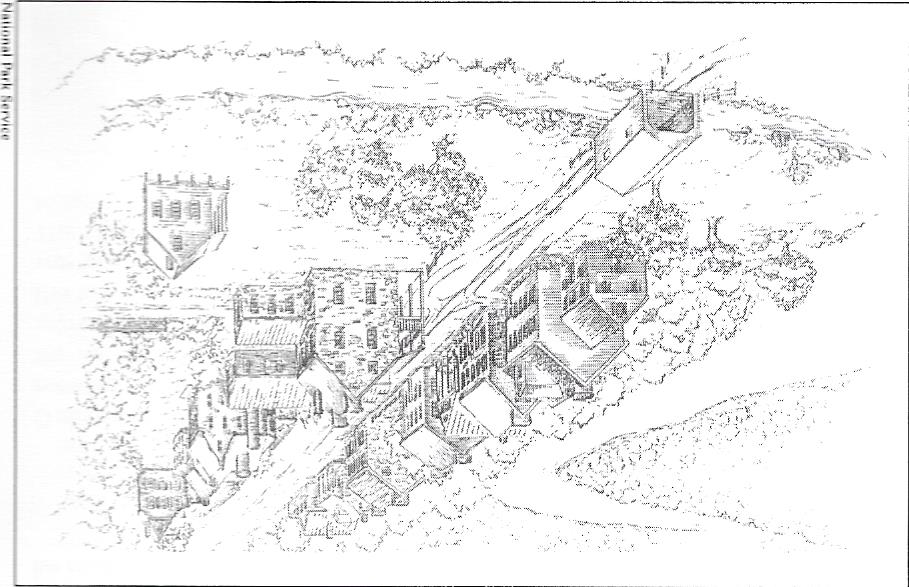

Gallatin’s dream was to establish an industrial community on the banks of the Monongahela River, similar to what he remembered of his birthplace, Geneva. He purchased 650 acres along the river, about a mile from his estate. There, he established a glass works, a gun factory, a distillery, a saw mill and a grist mill in the town that he named New Geneva.

Hamilton again…

But politics soon distracted Gallatin from New Geneva. He was selected as a delegate to the Pennsylvania Constitutional Convention in 1790, and was subsequently elected to the state legislature. By 1793, he was elected by the legislature to the United States Senate – where he and Hamilton became instant enemies.

Gallatin objected to Treasury Secretary Hamilton’s financial plans for the United States, such as the plan to federalize the states’ Revolutionary War debts. He became such a thorn in the side of Hamilton’s Federalist Party that the Federalists raised an objection to Gallatin’s election as Senator, because he had only been a citizen for 8 years. The Constitution required 9 years. In a vote along partisan lines, Gallatin was expelled from the Senate.

But Albert Gallatin’s political career was far from over. Storms were brewing on the western frontier, and Gallatin would be a key figure in the coming crisis.

Watch for my next post on the Whiskey Rebellion, coming soon!

Sources

Murray, Meridith A. To Live and Die Amongst the Monongahela Hills: the Story of Albet Gallatin and Friendship Hill. Eastern National, 1991.

Eleven 18th-century Buildings in Allegheny County

After visiting the Old Stone Tavern last summer, Al and I got curious about how many other 18th-century buildings still exist in the Pittsburgh area. We discovered that there are at least eleven, and we visited all of them, either on the trail for previous blog posts or over the past two weeks. Our trip took us all over the county, from Bethel Park to Leetsdale.

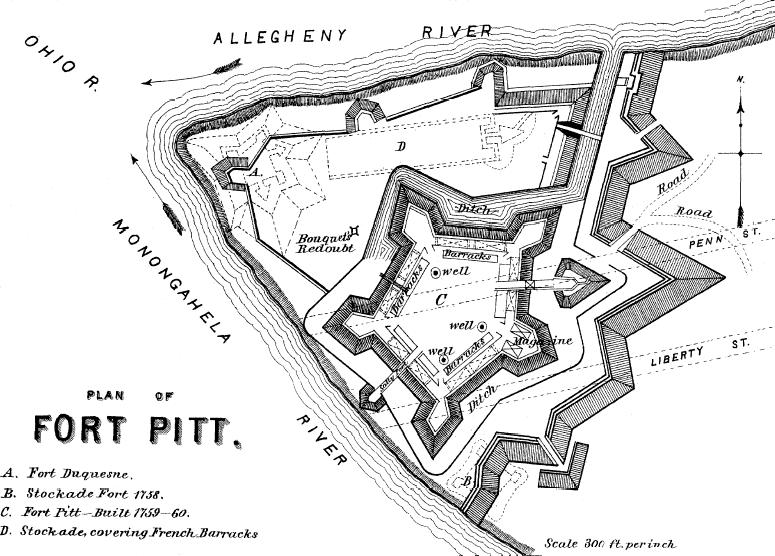

FORT PITT BLOCKHOUSE (1764)

The Blockhouse is the oldest authenticated building west of the Allegheny Mountains. Originally constructed in 1764 as one of five defensive redoubts for Fort Pitt, it is the only still-standing remnant of the fort. It was spared when the rest of the fort was demolished in 1795 because it was already in use as a residence by Isaac Craig. The sturdy little building continued as a home for about 100 years. By the late 19th century, Mary Schenley owned it and was persuaded to donate it to the DAR. The DAR opened it as a historical site and museum in 1894. The blockhouse stands in the middle of Point State Park, but it is still owned and operated by the Fort Pitt Society of the DAR.

Pre-pandemic, the museum was open in the summer from 10:30-4:30, Wednesday through Sunday. Winter hours are shorter, and you should call the Society to check on current hours of operation.

NEILL LOG HOUSE (1765)

The Neill log is the oldest building in Pittsburgh that was originally built to be a home.

John Neill (or Neal) immigrated from Ireland in 1736 and settled near present-day Harrisburg. He later brought his wife, Margaret, and seven children from Ireland to the New World, where he and Margaret had two more children. Two of his sons established homesteads near Indiana, PA. His son Robert bought 262 acres on the present-day site of Schenley Park and built the log cabin that stands there today on East Circuit Road, right up against the golf course.

Robert Neill helped to establish a Conestoga-wagon trade route between Philadelphia and Pittsburgh, and was a wagoner on that route. He and his partner, Jack Andrews, were several times attacked by Indians as they traveled back and forth.

One evening, they were starting down the hill near the present-day corner of Murray and Forbes Avenues, when an Indian threw a wasp’s nest at one of their horses. The wasps began to sting the horses and passengers, the horses bolted, and Neill and Andrews raced for the log house just ahead of their attackers. The party of Indians then besieged the house for an hour before giving up.

Neill sold the homestead to John Reed, another wagon trader, in 1787 (some sources say 1795), and moved to Market Square. The house eventually passed to James O’Hara, who left it to his granddaughter – Mary Schenley again – in his will. Mrs. Schenley donated the cabin to the City of Pittsburgh in 1883.

The log house was taken apart, all but the chimney, and completely rebuilt on site in 1969.

TITLENURE (1770)

Located at 3215 Kennebec Rd. in Bethel Park, this private home is registered with the Pittsburgh Historic Landmarks Foundation, but Al and I were unable to find any historical information about it.

WYCKOFF-MASON HOUSE (1775)

This log house, at 6133 Verona Rd. in Penn Hills, was built in 1775 by Isaac Wyckoff. It is still a private home and is operated as an Air B&B. See the Air B&B site for pictures of the lovely, authentic colonial-era interior.

WOODVILLE (1780)

Virginia native John Neville arrived in Pittsburgh in 1774 to command the Virginia troops at Fort Dunmore (later remained Fort Pitt), and started construction of his home, Woodville, around the same time. His home at Woodville survives on Washington Pike and was occupied until 1975. The house opens for tours only on Sundays, but Al and I spent an enjoyable hour poking around the grounds last fall when we followed Chartiers Creek from its source in Washington County to where it empties into the Ohio River at McKees Rocks (see this blog post).

Neville later built another home, Bower Hill, near the current location of Kane Hospital and Our Lady of Grace Church. At the time, Neville was one of the largest landowners in Western Pennsylvania. He owned 10,000 contiguous acres in present-day Mt. Lebanon, Scott, Carnegie, Rennerdale and Bridgeville.

THE OLD STONE TAVERN (c. 1782)

See my earlier blog post about this fascinating site. 1782 is an approximate date for the Tavern’s construction. It may date as far back as the 1750s.

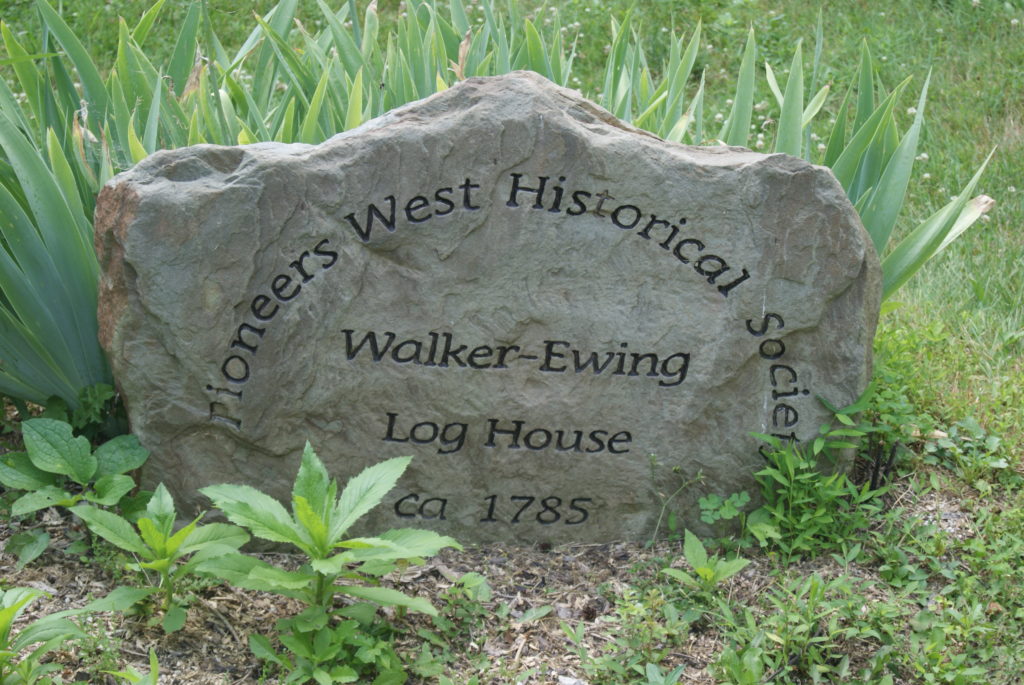

WALKER-EWING-GLASS LOG HOUSE (c. 1785)

This is the “settler’s cabin” that Settlers Cabin Park is named after. A small cabin with a very sturdy chimney, it sits just inside the park on Pinkerton Run Rd. The site is lovely, with a pretty little stream running in the wooded valley below and a chicken coop nearby where we saw a teacher giving a talk to a group of preschoolers. The children were much more enchanted by the chickens than by anything that their earnest teacher had to say!

The cabin is said to have been built in the 1780s by John Henry, a Scots-Irish fur trader who came to Western Pennsylvania around 1760. In 1772, Isaac and Gabriel Walker migrated to Western Pennsylvania from Lancaster and acquired a 437-acre estate which they named “Partnership.” In 1785, they bought the nearby Walker-Ewing-Glass cabin from Henry.

WALKER-EWING HOUSE (c. 1790)

Gabriel Walker built this second house around 1790. It stand less than a mile from the first house, on Baldwin Rd. near Noblestown Rd. It is thought to have originally been more a hunting cabin than a primary residence.

The Gabriel brothers had some hair-raising adventures in the Western Pennsylvania wilderness. In 1782, their estate was raided by Indians, who killed two of Gabriel’s sons and abducted another son and two daughters. The abducted children were returned 21 months later.

In 1794, Isaac and Gabriel were arrested as Whiskey Rebellion conspirators, and taken to Philadelphia. They were released after grudgingly paying the hated tax.

Isaac Walker gave the house to his daughter Jane and her husband Robert Ewing as a wedding gift in 1817. William and Jane’s son, Isaac Ewing was born in 1811, married Margaret Drake in 1834, and raised seven children with her. As of 1889, he was still living in the Walker-Ewing House. It was noted that he was a member of the United Presbyterian Church and a registered Democrat.

Ewing descendants lived in the house until 1973, when descendant Mrs. Robert Grace donated the house and land to the Pittsburgh History and Landmarks Foundation. She must have had a change of heart, because she later bought the house back and donated it to Pioneers West Historic Society. The Society maintains the house to this day.

THE JOHN FREW HOUSE (1790)

Also called the Sterrett House. Located in Pittsburgh’s Westwood neighborhood at 1566 Poplar Street, this is still a private residence. The original stone section of the house and the stone springhouse date to about 1790. The Greek revival addition dates to 1840.

TORRENCE HOUSE (1790)

Located at 121 Colson Drive in Pleasant Hills, this private home is registered with the Pittsburgh Historic Landmarks Foundation, but Al and I were unable to find any historical information about it.

JAMES POWERS HOMESTEAD (1797)

Located at 108 White Gate Road in O’Hara Township, this private home is on the Pittsburgh History and Landmarks Foundation register, but Al and I were unable to find any historical information about it.

SOURCES

http://www.fortpittblockhouse.com/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neill_Log_House

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wyckoff-Mason_House

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Pittsburgh_History_and_Landmarks_Foundation_Historic_Landmarks

Letters to Country Girls: 19th century self-help

Self-help books have been popular since Sebayt (“Teaching”) was written in Egypt in 2800 BCE. Written in the form of a letter of advice from father to son, it is the oldest known example of a genre that includes Hesiod’s Works and Days, Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations, the Book of Proverbs, Machiavelli’s The Prince and Benjamin Franklin’s Poor Richard’s Almanac. Human beings, bless our far-from-perfect little hearts, are self-improvers.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, “savior vivre” books were indispensable guides for men who wanted to know how to behave in polite society. But the genre really exploded in the United States in the 19th century, which saw the publication of books on topics from cookery and homemaking, to business success, weight loss and self-medication.

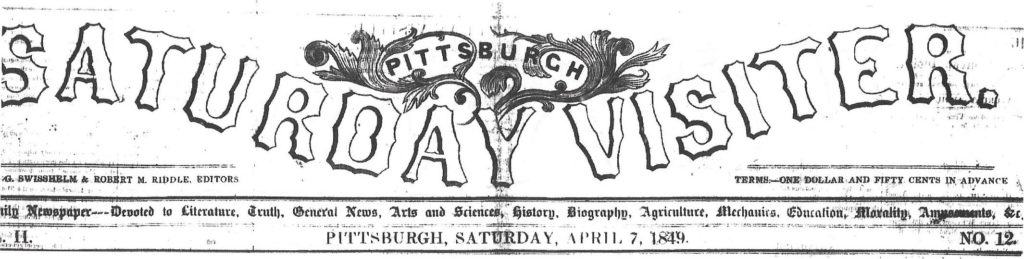

Jane Grey Swisshelm’s contribution to the self-help genre was her Letters to Country Girls. The Letters started as a series of columns in her newspaper, The Pittsburgh Saturday Visiter. She meant to write only a dozen columns, but the feature was so well-received that Jane ultimately wrote more than twice that number and collected them into her first published book in 1853.

The purpose of the Letters

Jane specified that she was not writing for middle-class city girls, whom she dismissively described as “these drawling concerns who lounge around reading novels, lisping about fashion and gentility, thumping on some poor hired piano until it groans, and putting on airs to catch husbands.” Her intended audience was girls growing up on the farms of Western Pennsylvania, young women who churned butter, made their own clothing, and might not see town more than monthly or a big city once in a lifetime. She respects these young ladies, thinks them worthy of bettering themselves, and sees herself – a young farm wife herself, before she became owner/editor of a Pittsburgh newspaper – as singularly positioned to advise them.

The letters are written in an intimate, conversational style, with touches of breezy, sometimes scolding humor. They read less like newspaper columns than like letters from a wry, loving aunt only a few years older than the recipient. Jane provides advice on a wide range of subjects: how to keep worms from peach trees, build a wire fence, make different colored dyes, cook peach butter and ketchup, even how to make papier-mache furniture tops and artificial flowers and grapes to adorn readers’ parlors.

“Get yourself a nice little sprouting hoe”

She was adamant, from her first letter, that every young woman must have her own hoe. “Some day when you go on an errand to the village, and ride a horse to be left at the blacksmith’s, just get the man of the anvil to make you a nice little sprouting hoe! You can send him a couple of pounds of butter for it.” She goes on to describe to her readers how they may trick a husband or brother into making a handle for the hoe. “Don’t patch (his) coat until the handle is in the hoe! If that does not do, go to the woodpile some day, about eleven o’clock, and work very busily until they come in for dinner. It will not be ready, you know; and they can put a handle in the hoe while you get dinner.”

With your hoe, she advises her reader, you can dig up woodland wildflowers and small trees to beautify your yard, or a little tansy to keep the worms away from you peach trees, and transplant wild berries and grapevines into your garden. It has other uses: “Sometimes it will do for a cane to help you to spring over muddy places and across runs. When you clamber up steep places you can hook it fast to a tree, bush, or projecting root, to help you up….If you meet a snake, you have a weapon to kill him with…In fact, of the two, a little hoe, as a companion in a morning walk, is decidedly preferable to a full-grown beau.” Jane thus anticipates the guy-code “bro’s before ho’s” by 150 years, and turns it on its head: “hoes before beaus.”

19th-century housekeeping advice

Jane provides advice on efficiencies and economies in housekeeping, not because she believes that housekeeping should be the center of a woman’s existence, but because she understands that it must be done – and, if it is completed efficiently, her readers will have something to spare for self-care and self-improvement. She admonishes her country girls to keep their bodies as clean as their teapots and to care for their complexions as carefully as their carpets.

Love of nature

Jane also urges her girls to cultivate a love of nature. Modern urban people might assume that that would have come naturally to our rural ancestors, but the tone of Jane’s letters hints that country people of 200 years ago saw nature mostly as something they must conquer or hold at bay via endless drudgery. Jane urges her readers to awaken to the beauty around them. She especially advocates cultivating a love of flowers. And she writes this about humble moss: “See how thickly it covers the old rotten log, as if it would hide its decay from those tall forest lords who now stand where it once stood…while this old tree that perhaps bore the very acorn they sprang from, is mouldering to dust at their feet. The green leaves it once bore, the rough bark that protected it, are gone; but the beautiful moss creeps over and covers it up so lovingly. Moss is like the mantle of charity, too, for it covereth a multitude of faults.”

She wants her readers to tend to their souls, as well as their bodies. Jane is an advocate of reading, but not for pure entertainment. She is scornful of city ladies who lounge around reading romantic novels. She advocates instead for daily Bible reading, and for forming Reading Societies, where country folk can socialize and discuss serious books and current events.

Feminism in the Letters

Jane writes from a feminist perspective. In letter #10, she excoriates men who see their wives and daughters as they see their farm animals. The women in their families are resources, to be worked to exhaustion in the fields and barns, and then come back to the house to cook, churn and scrub while the men rest from their labors. Women had no vote in the 19th century, and little legal recourse. A woman’s labor and property belonged to her husband. Jane points out that the legal situation encouraged men to see women as property. “If Sallie has no right to hold office in church or state – if she is to submit to me in all things, of course I must be wiser than she, and better too. She is ‘heaven’s last best gift to man’, an’ mighty useful one can make her!” But, she goes on, “let one presume to use her mental powers – let her aspire to turn editor, public speaker, doctor lawyer – take up any profession or avocation which is deemed honorable and requires talent, and O! bring the Cologne, get a cambric kerchief and a feather fan, unloose his corsets and take off his cravat! What a fainting fit Mr. Propriety has taken!”

But…

Jane was a farmer’s wife herself, and understood how hard the work was. She didn’t object to a woman helping out with the men’s work on the farm. In #14, she writes, “If you have plenty of help in the house, there is nothing unfeminine or unhealthy in tossing hay, or raking grain.” But her point is that such assistance should go both ways. “When she requires his assistance at her work, let him return the favor.” She is ever an advocate for a marriage of equals, where husband and wife support each other, ever an advocate for women getting enough relief from drudgery to have a life of the soul and the mind, ever an advocate for education and self-improvement.

The book is a genuine delight, and available to read on Google Play for free. Just follow this link: https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=Rt4-AQAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&pg=GBS.PA7

Sources

Swisshelm, Jane Grey; Letters to Country Girls, New York: J.C. Riker, 1853.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Self-help

http://www.bbc.com/culture/story/20140805-the-ancient-roots-of-self-help

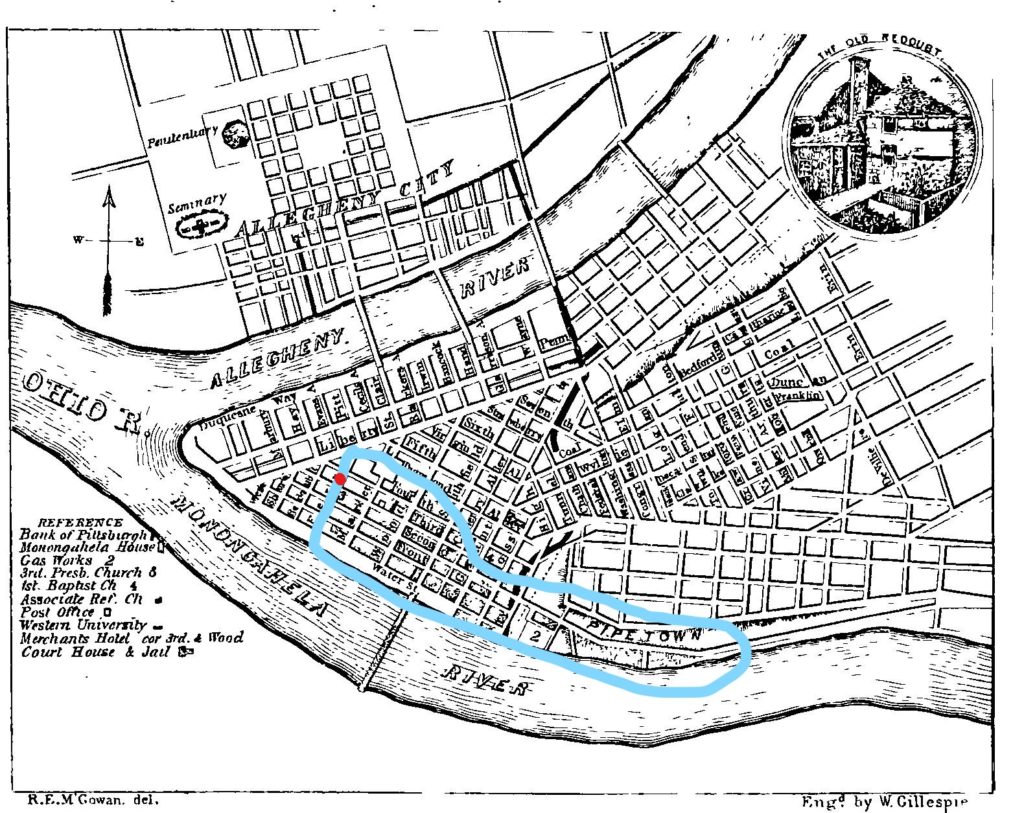

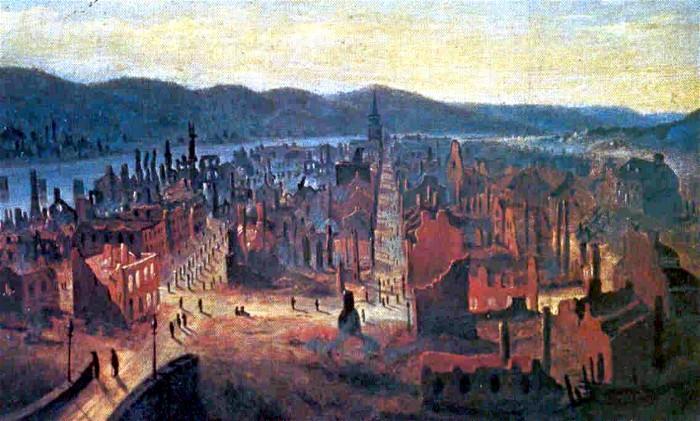

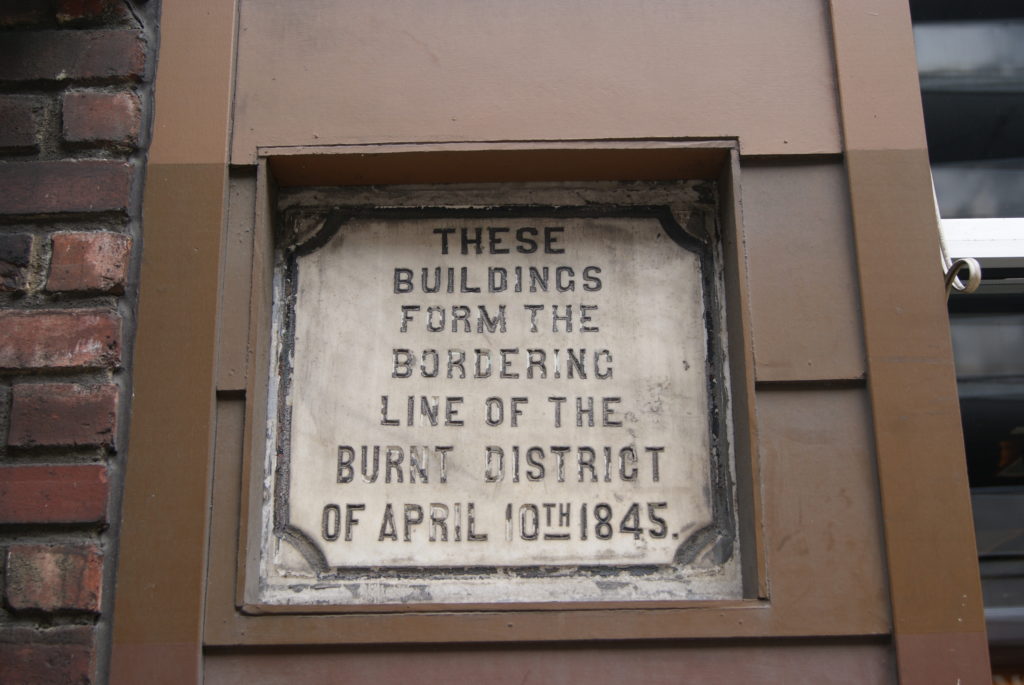

The Pittsburgh Fire of 1845

In this time of plague, it seems fitting to remember how people survived past calamities. And we are approaching the anniversary of a great local catastrophe: the Pittsburgh fire of 1845, a turning point in my upcoming novel Righteous.

Pittsburgh’s great fire is almost forgotten now, but for many years, the city commemorated the date by ringing out 1 – 8 – 4 – 5 on the old City Hall bell at noon on the anniversary, April 10. Articles about the fire appeared regularly in newspapers on the anniversary date, major ones appearing on the 25th anniversary in 1870, and following the similarly-devastating flood in 1936.

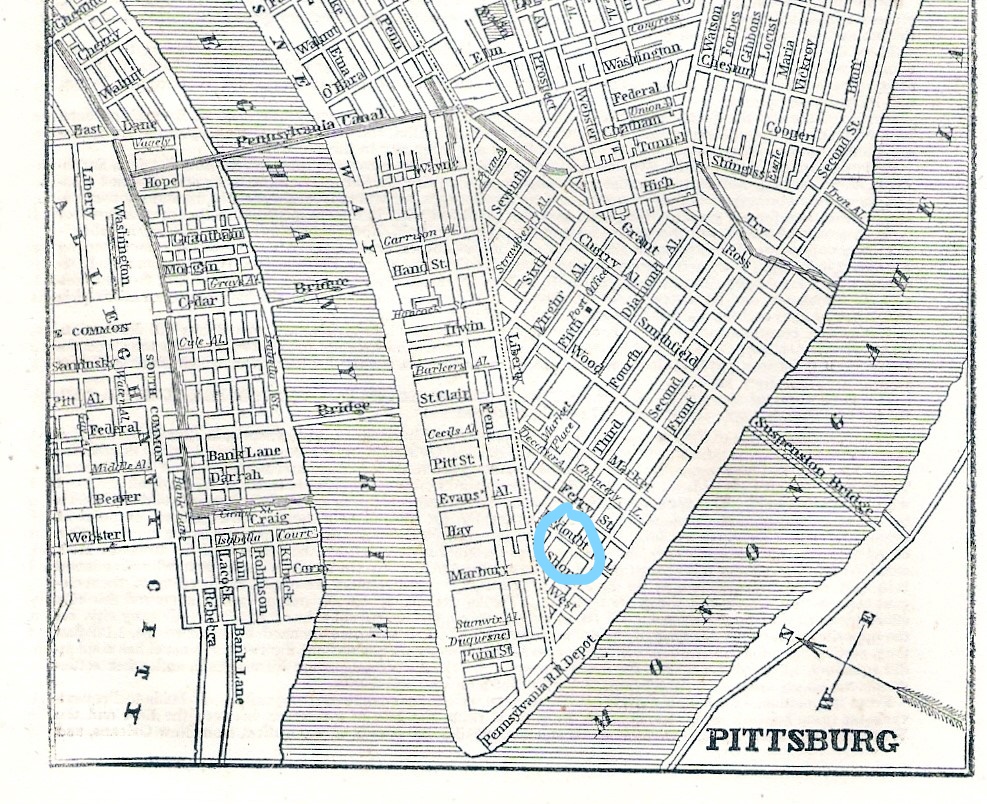

Origin of the Fire

Whenever there was a fire in a major city in the 19th century, some poor Irish woman always seemed to get the blame. But the story of Mrs. O’Leary’s cow in Chicago turned out to be apocryphal, and the origin story of the Pittsburgh fire is also in doubt. The story goes that the fire was started by Ann Brooks, an Irish washerwoman who worked for Colonel William Diehl on Ferry Street (present-day Stanwix Street). Mrs. Brooks was said to have started a fire to heat water for Col. Diehl’s laundry. She left it unattended and a spark ignited a nearby ice shed.

We don’t know whether Mrs. Brooks was really to blame, but it is undisputed that the fire started somewhere near the corner of Ferry and Second Streets and that it destroyed 60 acres, about 1/3 of the young city. Estimates of the total damage range from $6 million to $20 million. The best estimate is about $12 million, or $267 million in 2020 dollars.

Pittsburgh’s Preparedness (or not)

Also undisputed is that the city of Pittsburgh was as unprepared for the 1845 fire as our nation has been for the current pandemic. In 1844, the city built a new reservoir on Bedford Avenue to replace the old one that stood at the current location of the Frick Building. But the water mains and pumps were inadequate, leading to poor water pressure. The city had no municipal fire department. Six competing volunteer fire companies provided protection. They were well-intentioned but very poorly trained and equipped.

Conditions were against the city, too. Houses and businesses stood shoulder to shoulder, and the air was thick with flour dust, coal dust, soot and cotton fibers from the city’s many mills and factories. Sources say that no rain had fallen in anywhere from 2 to 6 weeks. 6 weeks of no rain in a Pittsburgh spring seems implausible, but all sources agree that it had been a dry spring and the reservoir was very low.

The fire spreads

The day of the fire was warm and windy.

A volunteer fire company arrived on Ferry Street soon after the ice shed fire was reported, but by then the flames had spread to the nearby Globe Cotton factory. Still, the fire could have been controlled at that point had the fire fighters not been hampered by low water pressure and their own rotted hoses

The fire raced up Second and Third, nearly destroying Third Presbyterian Church. The wooden spire of the church caught fire and the church was only saved by fire fighters cutting off the spire and letting it drop to the street.

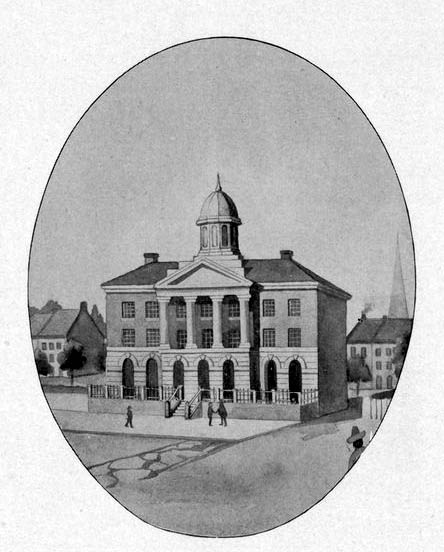

The flames reached their peak in Pittsburgh’s first and second wards between 2 and 4 p.m. Winds blew the fire south and east, destroying the city’s pride and joy, the elegant Monongahela House Hotel, as well as the Courthouse and Western University, predecessor to the University of Pittsburgh. The wooden Monongahela Bridge also burned, to be replaced by the first Smithfield Street Bridge.

Bank of Pittsburgh

The Bank of Pittsburgh, built entirely of stone and metal, was supposed to be fireproof. The head cashier calmly locked the bank’s cash, books and records in the vault before vacating the building and standing on the street with other onlookers. When the building’s zinc roof melted, the interior burst into flames and was entirely gutted. The vault itself was fireproof, and the bank’s valuables remained intact, but the destruction of the building caused panic. People who had been merely observing the fire rushed home to try to save their possessions. Soon, carts full of boxes, furniture and other property clogged the chaotic streets. Most of these goods ended up abandoned, and either burned or stolen. Some people escaped across the Monongahela Bridge before it burned. Some fled northeast to the present-day Hill District, and courageous ferry operators transported many others to safety.

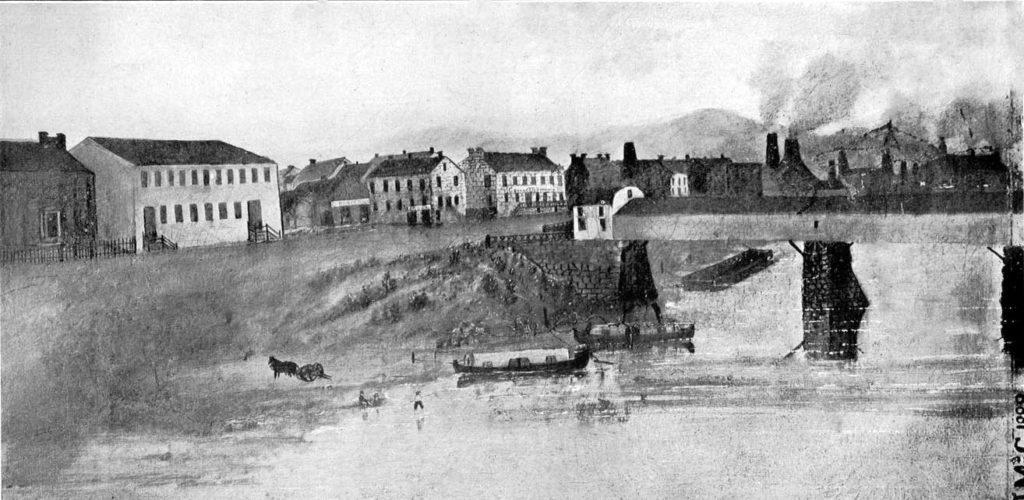

Destruction of wharf and Pipetown.

The flames raced along the Monongahela Wharf, destroying the docks, the warehouses and any boats that hadn’t cast off down the river in time. The destruction at the docks might have been contained if a barrel of liquor hadn’t fallen and burst right in the path of the flames, igniting nearby straw and the rest of the liquor warehouse.

The fire followed the Monongahela River towards Pipetown, an industrial suburb that lay below what was then called Boyd’s Hill (now called simply The Bluff, the present-day home of Duquesne University). There it randomly spared many factories while destroying others, including the city gas works, Miller & Co. glass works, and Dallas Iron Works. Finally, around 6 in the evening the winds died down, and by 7 p.m. the fire had burned itself out on the slope of Boyd’s Hill.

Cost of the catastrophe

The fire destroyed 10-12,000 buildings, displacing 2000 families, or about 12,000 people. A sampling of the businesses burned to the ground include the offices of the Daily Chronicle newspaper, the garage and all equipment of the Vigilant Fire Co., the Weyman Tobacco Factory, six drugstores, 4 hardware stores, 5 dry goods stores, 2 book shops, 2 paper warehouses, 5 shoes stores and 3 livery stables. Every insurance company in the city except one was bankrupted.

Incredibly, only two people died in the fire – out of a population of about 20,000. Lawyer Samuel Kingston returned to his house on 2nd St. to rescue his piano. He fell into the basement of his house, was trapped there and died. A Mrs. Maglone or Malone was also reported missing the day of the fire, last seen at a shop on 2nd St. A set of bones found in a store at the corner of 2nd and Grant on April 22 were believed to be hers.

Recovery

Pittsburgh rose from its ashes almost immediately. The state provided a moratorium on state taxes and $50,000 in relief ($1.7 million in today’s dollars). Donations came from other parts of the country and all over the world. Individual contributions of note include $500 from future president James Buchanan, $25 from future Secretary of War Edwin Stanton and $50 from former president John Quincy Adams. The city of Wheeling, WV, contributed 100 pounds of flour and 300 pounds of bacon.

Property values skyrocketed, and a construction boom started on April 14, only 4 days after the fire. By June 12, while many streets were still blocked with fire debris, 500 new buildings were either completed or in progress. Fine buildings of brick or stone replaced the destroyed wooden tenements.

Pittsburgh came back from the great fire bigger and better. I have faith that we will emerge from our current calamity renewed, refined and strengthened.

And an aside…

A tidbit about the Monongahela House that I can’t bear to leave out, but that didn’t fit into the flow of my overall fire narrative: Presidents Lincoln, Garfield and McKinley all stayed at the rebuilt Monongahela House in the years following the fire. Garfield and McKinley slept in the same bed that Lincoln had used – and all three men were assassinated! The furniture from the “Lincoln Room,” including the unlucky bed, passed into the hands of Allegheny County when the Monongahela House was torn down in 1935. The County placed the furniture in a small museum on the grounds of South Park. The furniture was subsequently stored in a warehouse in South Park, where it didn’t come to light again until 2006. The bed is now in the possession of the Heinz Pittsburgh History Center.

Sources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Fire_of_Pittsburgh

http://www.steelcactus.com/PGHFIRST_1.html

My friend and former work colleague, Gary Link, has written a series of novels that take place in mid-19th-century Pittsburgh. The Pittsburgh fire is the central event of the first book in the series, The Burnt District:

Robert M. Riddle

In the 1840s, at least six newspapers were published in Pittsburgh, including the Pittsburgh Catholic, the Daily Gazette, the Daily Morning Post, the Mystery, the Spirit of the Age and the Commercial Journal. But, only one editor was brave enough to not only publish the work of a female journalist, but to support her when she became the first woman in the United States to start her own newspaper.1 Robert M. Riddle, editor of the Commercial Journal, and later mayor of Pittsburgh, deserves to be better known.

The year was 1847. The abolitionist newspaper The Albatross had just ceased publishing, and the Liberty Party (a forerunner of today’s Republican Party) was without an advocating newspaper. Jane Grey Swisshelm marched into Robert Riddle’s office one day in the autumn of 1847 and announced that she intended to start her own abolitionist paper and she intended that Riddle should print it.

The Pittsburgh Saturday Visiter

At the time when she marched into Riddle’s office, Swisshelm had been writing for the Spirit of the Age and its successor the Commercial Journal for about three years. So, she had newspaper experience. But, even then, before competition from television and the internet, newspaper publishing was often unprofitable. The Albatross and the Mystery had folded in the past two years. It was far from obvious that Pittsburgh needed another newspaper. Riddle initially tried to talk Swisshelm out of her scheme. In her 1880 memoir, she quotes his exact words: “Are you insane?” He begged her to think it over, consult her husband and her friends. He reminded her that she would be a woman working in a newsroom completely dominated by men, which would seem scandalous to many.

As in so many turning points in her life, Jane Swisshelm was unpersuadable. She wore down her husband’s objections, she wore down Riddle’s objections, and she invested most of her inheritance in the newspaper she named the Pittsburgh Saturday Visiter. (Yes, that was how she spelled ‘visitor’; she insisted that it was correct, and people soon grew tired of trying to argue Jane out of anything).

Pioneers

Swisshelm published the first issue of the Visiter on December 20, 1847, and the newspaper had 6000 subscribers by the end of 1848.

Jane admitted that interest in the new paper was partly driven by the sensation of a lady publisher. As Riddle had predicted, the public was both intrigued and scandalized. Jane was small, pretty, and looked younger than her 32 years. No photographs of Robert Riddle exist, but he was only 35 when he started printing the Visiter, and Jane’s own account describes him as “one of the most elegant and polished gentlemen in the city, with fine physique and fascinating manners.” Jane’s biographer, Sylvia Hoffert, points out that “Neither Jane nor Riddle had ever worked as an equal in an office with a member of the opposite sex. And they knew only one other man and woman in Pittsburgh who had done so.” They had to make it up as they went along.

To demonstrate that their relationship was strictly business, Riddle had the shutters removed from the windows of the Commercial Journal offices. So, the curious public had a direct view into everything that went on in the newsroom. He and Jane took care never to be seen alone together. If Riddle escorted Jane anywhere, his wife was also present. Jane went out of her way to look unattractive and unfeminine when she was working in the newspaper office. She was so successful that Riddle at one point asked her why she was always covering her hair with “hideous caps.”

Business Partnership: Robert M. Riddle & Jane Grey Swisshelm

Their partnership worked well. Published weekly, the Visiter carried political news and commentary and market reports, and re-printed literary and general-interest articles from other newspapers. Hoffert speculates that Riddle had reasons of his own for supporting the Visiter. He certainly knew and respected Jane’s work as a writer and reporter. But the Commercial Journal published mostly business news such as commodity prices, steamboat schedules and advertisements. Riddle published some political news, but tended to stay away from editorializing, perhaps to avoid antagonizing Pittsburgh’s business community. Hoffert surmises that Riddle saw printing the Visiter as a way of promoting abolitionism, women’s rights and temperance, but at a deniable remove.

The two didn’t agree on everything. They disagreed ferociously about the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. Riddle was an abolitionist, but counseled obedience to the Act as the law of the land. Swisshelm remarked in her newspaper that “any of our southern friends who want business done in their line in our dirty city, should direct their communications to our good friend, Robert M. Riddle.”

As Riddle predicted, even with 6000 subscribers, the Visiter struggled to make a profit. In 1849, desperate to raise some capital, Swisshelm sold half her interest in the paper to Riddle. Later that year, Jane’s brother-in-law, William Swisshelm, bought Riddle out. But by 1854, the newspaper was bankrupt, Jane’s estate was gone, and she and William sold the Visiter to Riddle. He continued to publish it under the new name the Family Journal and Saturday Visiter. But Pittsburgh’s days of boasting the only female newspaper publisher in the country were over. However, Jane went on to publish another newspaper in St. Cloud, MN, and to work as a hospital and battlefield nurse in the Civil War. Read more about that in my upcoming book Righteous2.

Robert M. Riddle early life

But what of Riddle? Let’s go back to the beginning….

The Riddles were a prominent family in Pittsburgh in the 19th century. Dr. D. H. Riddle was the pastor of Third Presbyterian Church in Pittsburgh, Samuel Riddle ran for state assembly in 1834, John M. Riddle ran a school on Wood Street, and another Riddle published the first Pittsburgh directory, Riddle’s Directory. J.W. Riddle was Treasurer of Allegheny Savings Bank. Mid-19th century directories also list Riddles as drovers, shopkeepers, a whip manufacturer, a millwright, an attorney, a carpenter, a “cage maker,” and two “widows.”

Robert’s father, James Riddle, was an attorney, a stock broker, a judge and a very well-known and well-respected person in the Pittsburgh community. He ran for the U.S. Senate as a Democrat in 1825, but lost.

After attaining his degree at Washington & Jefferson College, Robert formed the wholesale mercantile firm, Riddle & Forsyth, with partner Jacob Forsyth. The business failed, and Robert went to Philadelphia to work in banking, as Forsyth picked up the pieces of Riddle & Forsyth and went back in the wholesale business on his own.

By 1837, Riddle was back in Pittsburgh editing a Whig newspaper, the Daily Advocate & Statesman. He served as Pittsburgh postmaster from 1841-5, and had the distinction of appointing the first letter carrier. Before that, everyone had to go to the post office to pick up their mail.

In 1845, he took over the Spirit of the Age and renamed it the Commercial Journal, which is where we first met him. In 1858, his health failing, he sold the Commercial Journal to Thomas Bigham, an ardent Republican whose house was a stop on the underground railroad. The Commercial Journal was merged with the Pittsburgh Gazette in 1861, forming the Daily Pittsburgh Gazette & Commercial Journal.

Robert M. Riddle in politics

Riddle was prominent in the Whig party, serving on many committees and delegations. In 1853, he ran as a Whig against Democratic incumbent mayor William B. Guthrie, and won with 1887 votes to Guthrie’s 1568. His one-year term as mayor seems to have been uneventful, and he was not re-nominated, but this anti-Riddle campaign ditty lives on in Pittsburgh’s historical records:

An avid Pittsburgh promoter, Riddle was involved in the effort to extend the Chambersburg Railroad to Pittsburgh. He was also a founder of the Republican Party and was present at the first Republican National Convention in Lafayette Hall in Pittsburgh in 1856. Robert M. Riddle died of inflammatory rheumatism on December 18, 1858, and is buried in Allegheny Cemetery in Pittsburgh.

Notes and sources

NOTES:

- Jane Grey Swisshelm was, to my knowledge, the first American woman to start her own newspaper, but she wasn’t the first female newspaper publisher. That honor belongs to Elizabeth Timothy, who assumed the role of publisher of the South Carolina Gazette when her husband, Lewis Timothy, died. She later handed the newspaper over to her son.

- Publication date of Righteous is not yet determined, based on the current virus crisis and the sale of my original publisher to a larger house.

SOURCES:

Hoffert, Sylvia, Jane Grey Swisshelm, An Unconventional Life; University of North Carolina Press, 2004

Swisshelm, Jane Grey, Half A Century; self-published by author, 1880

https://historicpittsburgh.org/islandora/object/pitt%3A00ach3238m/viewer#page/1/mode/2up

https://historicpittsburgh.org/islandora/object/pitt%3A31735064610037/viewer#page/6/mode/2up

https://historicpittsburgh.org/islandora/object/pitt%3A00hc03974m/viewer#page/136/mode/

https://historicpittsburgh.org/islandora/object/pitt%3A00avl7273m/viewer#page/30/mode/2up

https://historicpittsburgh.org/islandora/object/pitt%3A31735056287505/viewer#page/414/mode/2up

Doughboy

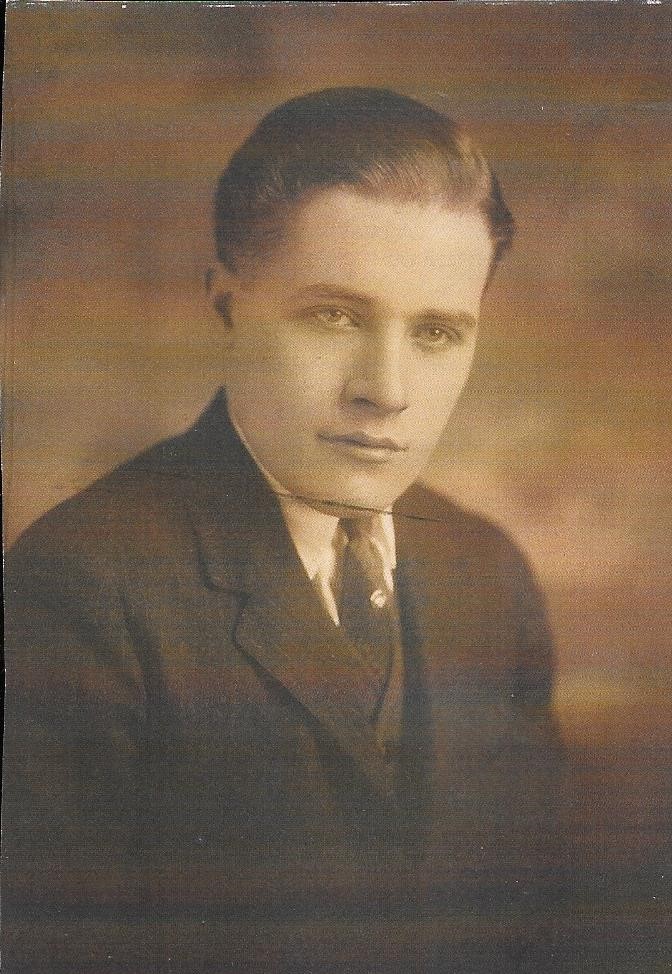

After I posted the short-story about my grandmother, I remembered this story that I wrote about 15 years ago, based on my grandfather’s very short service in World War I. In this story, I imagine my grandmother as having a teenage crush on the older Nock Yaggi, and I hint at a future for my grandparents very different from the lives they actually lived. This story has never been published before…

Nock shouldered his way through the crowds to approach Mike’s coffin. He wouldn’t see Mike, of course. Mike’s body was buried somewhere France. But atop the coffin stood a picture of Mike in his Doughboy uniform, taken right before he shipped out. Elaborately framed in leaf-and-flower carved gilt, draped with black ribbon, Mike gazed defiantly at the viewer frowning a little as if skeptical that his glory days would be brief, that his life would shortly end in a dusty trench under a foreign sun.

The atmosphere at McDermott’s Funeral Home was almost festive on this hot August night in 1918. Bodies were packed elbow-to-elbow, smelling of sweat and of suppers of cabbage or garlicky sausage. The men’s necks glistened with perspiration over their starched collars, and the girls’ frothy white dresses wrinkled from the press of the crowd. The matrons forming a protective circle around Mrs. Yerkovich discreetly dabbed at their faces with handkerchiefs to pat away the sheen of sweat. Everyone talked at once, in low voices, of the first local boy to fall in the Great War.

Nock knew it wouldn’t be polite to admit it, but he envied Mike’s hero status. At least he got to go. Almost everyone except Nock got to go. Mike, Frank Loeffler, and Leo Braun all enlisted the day after high school graduation. Even Leo’s younger brother, Karl, was allowed to skip his last year of school and sign up. Only Nock was forced by his family to wait until his 18th birthday, still two months distant.

They just wanted to keep him a slave in the family furniture business, was what Nock had been a slave to that furniture store for as long as he could remember. As soon as he could hold a broom, he was sweeping the sidewalk in front of the store. Every spring, he painted the wooden stoop, and his parents had insisted that he take the business course in high school so that he could keep the books for the store when he graduated. He had spent his summer sitting on a stool in the office behind the store, adding up sums in a ledger, unspeakably bored, the electric fan solemnly shaking its head back and forth, back and forth, as if forbidding him to imagine any other life. Once every morning and once every afternoon, he stepped out into the alley behind the store for a cigarette. If he wasn’t interrupted by a delivery, or by a neighbor or workman taking a shortcut through the alley, he could daydream undisturbed by debits and credits.

Nock wasn’t sure where he was meant to make his life, but it was surely somewhere other than Yaggi & Junker Furniture in McKees Rocks, Pennsylvania, four miles down the Ohio River from Pittsburgh. Did no one but him see the irony of being in the furniture business with a family named Junker? When Nock pointed this out to Sylvester, his brother just rolled his eyes and said, “Yeah, Nock, real funny. You oughta be in vaudeville.” Sylvester, 24 and married, was humorless as far as Nock could tell. Well, he could work in the furniture store with the Junkers for the rest of his life if he wanted. Nock had bigger plans. Well, not plans exactly. He didn’t know for sure what he wanted to do, but he knew it wouldn’t have anything to do with ledgers and that it wouldn’t happen in McKees Rocks.

Maybe he belonged in California, working for the movies, or on a ranch in Montana, or in Africa hunting wild game like Roosevelt. Best of all would be to join his friends in France, fighting to make the world safe for democracy. Mike had gotten a leave before he shipped out and Nock’s heart twisted with envy of the snappy Doughboy uniform, and the gun. Working in the furniture business had given Nock an appreciation for fine wood, and Mike’s Springfield rifle was one high-quality article: glossy and substantial. Nock itched to heft it to his shoulder and hook his index finger around the satiny steel trigger, but Mike wouldn’t let him try it out. He said he had orders not to let civilians handle his equipment, but Nock was pretty sure he was just showing off.

After standing solemnly before Mike’s picture for a respectful amount of time, he began to make his way back through the crowds, so that he could slip into the alley and have a smoke. There was that silly little Mary Grant watching him. The minute he’d walked into McDermott’s, she came bouncing right up to him, bold as a stallion, “Hi, Nock!” with a big sassy grin on her face, swinging her head so that the braid down her back tossed. For crying out loud, she was maybe 14, didn’t even put her hair up yet. Anyway, if she had her eye on him she should just forget it for a lot of reasons. First, Nock doubted that he would ever get married. Second, if he ever did get married, first he intended to see the world, starting with France, where he was pretty sure that buxom French mademoiselles were happy to be kissed or more by the sharply-dressed American soldiers come to save their country from the Huns for them.

Nock had escaped to the alley and lit his cigarette and was just enjoying himself imagining the red wine and the mademoiselle and what her breasts might look like, when he felt a tap on his left shoulder. He turned his head in that direction, but felt a swift movement behind him and spun his head the other way to see Mary Grant’s grinning face behind him on the right.

She laughed. “Hi, Nock Yaggi.”

“Hi.” He made only the briefest eye contact and inhaled some tobacco, hoping to give her the hint to go away.

Instead, she leaned against the wall behind him, one leg bent, with its foot flat on McDermott’s wall. “Shame about Mike.”

“Yeah. You’re going to get your dress dirty leaning on that wall.”

“I don’t mind. It washes.”

“Free country, I guess.”

“Well, anyway, he was a hero and all.”

Nock tossed the remains of his cigarette across the alley. “Yeah. Well, I’m going as soon as I turn 18.”

“I though you were already 18.”

“October 10. I’m signing up that very day. My parents can’t stop me once I’m 18. I’m not so sure I’ll ever come back to McKees Rocks. I’d like to see what it’s like in New York City or maybe out west, after France. Or maybe I’ll even stay in France while after the war. I don’t know.”

“Oh, France. I’d just love to see France.”

He glanced over at her. “Well, you wouldn’t like it much now. Men shooting at each other across barbed wire. It’s no place for a little girl.”

Mary’s freckled cheeks flushed. “I’m 15, you know. Anyway, I’m talking about Paris, and I’m talking about after we win the war. And first I’m going to New York to sew costumes for the stage. Maybe I’ll even go out west to Hollywood and sew costumes for the movies.”

“Well, that’s nice.” He tapped out another cigarette and lit it, looking straight ahead and moodily blowing the smoke out of his lower lip.

“Could I try that?”

“What? Smoking?”

“Yes.”

Nock glanced around the alley. “What do you want to do that for? You’ll just get in trouble. Nice girls don’t smoke.”

“I just want to see what it’s like.”

He glanced both ways again and then passed her the cigarette. “Don’t inhale too deep the first time. You’ll get sick.”

He watched her anxiously as she inched the cigarette towards her lips and hesitantly sucked. She immediately choked and began to cough.

“See? I told you,” he said.

She held the cigarette away from him, stifling more coughing. “No, wait. Let me try it again,” she gasped.

“You’ll get sick,” he insisted.

Mary ignored him and inhaled again, turning away from him. This time, she emitted only one stifled cough.

She passed the cigarette back to him. “I just wanted to see what it was like.”

“Well, it’s not for girls. You know, New York City’s really no place for a girl all by herself either. What do your parents say about that? Where would you live?”

“They have hotels where the girls live who work on the stage. They all live together like sisters.”

“Oh. It’s like that out west if you work on a ranch. All the guys bunk in together. I might do that. Or I might go to work in the movies, too. I know bookkeeping, so I think I could do bookkeeping for a movie company, just to get my foot in the door, then maybe they’d let me do something more interesting.” He had gotten this idea a minute ago, when Mary talked about sewing for the movies.

“That’s a good idea.”

“Mary?” Once of Mary’s skinny friends, a girl in a black and white sailor dress, poked her head out the door into the alley. “Your mother’s getting ready to leave. She’s looking for you.”

“I have to go,” Mary said. “Maybe I’ll see you around before you go to France. Good luck.”

“Same to you.” He finished his cigarette and went back in to pay his respects to Mrs. Yerkovich.

Nock counted backwards from October 10 and marked on his office calendar the number of days until his 18th birthday. Monday through Saturday, from 9 a.m. until 6 p.m., he perched on his stool in the furniture store office scratching in the books, taking his cigarette breaks in the morning and afternoon, and walking home to have lunch with his parents. He tried to win a little respect from his father and brother by sharing his modern ideas about the business. For instance, why couldn’t they sell furniture on credit to some customers? Nock thought he did a good job of showing that, if they charged a monthly fee for the credit, they would actually make more money on every piece of furniture that they sold. “We’re the furniture store, not the bank,” Sylvester said dismissively. His father and Mr. Junker didn’t think that people should be encouraged to go into debt. They shouldn’t have the coat rack or the armchair until they had saved the money to pay for it. What about electric appliances? Couldn’t they look into adding electric appliance to their stock? Electricity was in almost every home now, and people were crazy about electric vacuum sweepers and the new electric iceboxes. They could make a lot of money selling electric appliances, Nock argued. His father calmly explained to him that they knew furniture, that was their business; they didn’t know anything about electric appliances. Nock felt like screaming at them, Well, then, find out! Nock wanted to scream, just in general, a good bit of the time. The whole world was changing, interesting things were happening, and he was trapped in the one place where nothing important was happening and nobody wanted anything to change.

Weekday evenings after dinner, Nock stayed home and caught up on the war news in the newspaper, then settled down with National Geographic or Popular Science. Sometimes on Friday or Saturday evening, he went to the movies or a vaudeville show with some fellows who were still in high school. One Saturday in September, he met Larry and Bob in front of the Roxian as usual, but Larry greeted him with, “No movie tonight, Nock. Something more interesting planned. You like ragtime, right?” When Nock nodded, Larry continued, “Well, there’s a new kind of music you got to hear, then. It’s called jazz. It’s like nothing you ever heard before in your life, Nock. They play it at some of the clubs in Pittsburgh.”

They waited for some more of Larry’s and Bob’s friends on the corner, then took the streetcar to Pittsburgh. Nock was surprised that Mary Grant and some other girls were among the group. In Pittsburgh, they transferred to another streetcar that took them into the Hill District east of the city center, a neighborhood of poor lighting and drooping, unpainted tenements populated by Syrians and Negroes. The club was claustrophobic with tobacco and another sweet-smelling smoke that Larry said he thought was called “hemp.”

They could barely see the small corner stage where a quartet of Negroes set up their instruments. For the next hour, Nock felt as far away as he had ever felt from his white-painted frame house on Second Street with its picket fence and his mother’s hollyhocks. The music felt dangerous. It wrapped itself around you like a snake, like the curling smoke from that sweet-smelling hemp. It got inside you and got your heart racing and your skin tingling, but at the same time you felt too relaxed to move. Nock was acutely aware of Mary Grant’s freckled arm a few inches from his, imagined that the very tips of its pale, fine hairs were yearning toward the hairs on his own arm. A few couples danced in the small space between the stage and the crowded tables, moving in a sinuous rhythm that Nock was embarrassed to watch. Towards the end of the set, a pretty Negro girl in oiled, marcelled waves and a short dress that looked like it was pasted on her wet, sang a few numbers in a husky lisp.

They were back on Broadway Avenue in the Rocks by 10, had walked the girls home by 11, and congratulated themselves on getting away with an adventure that would have scandalized their parents.

On Sunday, the Yaggis went to 10:00 Mass, then had an early dinner, with Sylvester and his wife Margaret in attendance, and then the endless dull Sunday afternoon stretched ahead. The day after the outing to the jazz club, Frederick Yaggi called Nock into the back parlor after Sylvester and Margaret left. Nock’s father was a square man, short, broad of shoulder and growing broader of waist. His complexion was florid, his hair the silver blond of a winter sun. Although born in the United States, he retained traces of his parents’ German accents, an embarrassment in these times, Nock thought.

His mother was already sitting in the parlor, twisting her handkerchief. Frederick sat down and gazed at his son sternly for a few long seconds. Nock’s heart began to flutter.

“I spoke with John Pfeffermann at church, Norbert, “Frederick began, “and what he told me was distressing to me.” Nock had been called Nock since babyhood. To be called by his given name of Norbert could only mean bad news. He remained silent.

Frederick continued, “Did you and Lawrence Beck and some other boys escort some young ladies to a Negro club in Pittsburgh last night?”

Nock kept his eyes locked with his father’s, afraid to look at his mother. “Yes, sir.”

“Mr. Pfeffermann makes deliveries to these places on weekends,” Frederick explained. “He was very shocked to see you young people in such a place. Do you have an explanation?”

Nock felt himself flush. “We wanted to see something more interesting than just another movie. We wanted to go someplace more interesting than the Rocks for a change.”

“You are not to go to such a place again,” his father said. “And you are certainly never to take a young lady to such a place.”

“Father, we were just listening to music. It was something really different and exciting. I – “

“Do not argue with me, Norbert. These places are not safe for nice young people. I expect to be obeyed.”

“Yes, sir. May I go now?” Nock felt a lump rising in his throat.

“Yes.” His father waved a hand as if to brush him away.

Nock left the house and walked up to the end of Chartiers Avenue, fuming. A fellow couldn’t do anything around here without being found out. Everything you did was watched and controlled and commented on. You couldn’t decide anything for yourself, not even what you did for fun or what music you listened to. He might as well be in prison.

He passed sagging Corny Mann’s Saloon, and continued up the hill through the cemetery. He stopped at Mike’s gave and tried to feel sorrow, but all he could feel was anger at his father and the sense of Mike’s being gone, just like he had been since he enlisted, like the other fellows were gone. Just not stuck in the Rocks like Nock. It was hard to get the sense of Mike never coming back. Maybe it would have been different if he’d seen the body in the coffin

Still full of rage and nervous energy, he strode back down the hill until he found himself at the river. It was the first cold snap of fall, with a wind that blew away the burnt-sugar smell of the coke ovens and the ashy smoke from the factories. Nock never minded the fog and smoke and odors from the mills along the rivers. To him, it was the smell of power and prosperity. It meant that fellows could find work, and machines could be made and the war won. It was a visible flexing of American muscle. He stood for a while and watched the tugs pulling the broad, flat barges down the Ohio, laden with hills of ebony coal or neat rows of timber or steel bars The railroad tracks along the river clattered with their burden of freight cars carrying corn from Illinois, cotton from Alabama, tanks and trucks to the coast for shipment to France. Everything and everyone except him seemed to be going somewhere else. He was marking time. But not for long. His birthday was nine days away.

His father kept him at the office late the night before his birthday for a man-to-man talk. Frederick solemnly fixed his small gray eyes on his youngest son. “Do you truly understand what you’re about to do, Norbert?”

“Yes, Father.”

Frederick shook his head. “I’m not sure you do. I’ve spoken with the Loefflers and the Yerkoviches and others. The letters that they receive from their young fighting men do not make a pretty picture.”

“I can read, Father. I know about the trenches and the gas.”

“The war has turned in our favor. I believe that it’s about to be won, with or without you. Why risk your life?”

“That’s just one more reason to sign up now, before I miss it altogether!”

Frederick sighed and removed his glasses. “Your mother is very distraught.”

“I know, Father, but I can’t help that. It’s my life. I have to be able to make my own decisions. I’m not going to die in the war. I know it.”

“A million young men already in their graves thought the same.”

Nock was annoyed to find himself near tears. “Well, I know I’ll die of boredom if I have to stay here much longer!”

Frederick gazed at his son in silence for a few seconds. “Your mother pleaded with me to forbid you to do this thing. That I cannot do. I see that you are determined. So!” He slapped his ham-hock thighs with his hands, then reached forward and placed a hand on Nock’s shoulder. “God bless you then, son. You will be in our prayers every day.”

Nock went the next day and signed up at the recruiting station on Chartiers. Only a week later, his father and Margaret saw him off at the railroad station in Pittsburgh. Sylvester stayed back and minded the store with Mr. Junker, and his mother had taken to her bed in distress.

Margaret hugged him, and his father clapped him on the shoulder and wished him Godspeed. “I’ll write,” Nock promised as he hopped into the train car. His heart was light as the train pulled out of Penn Station, leaving behind the sullen, oily Ohio, the little frame houses clinging to its hills and bluffs, and the spewing factories sprawled on its flats.

He spent the next four weeks in greasy New Jersey mud that he was sure couldn’t be any worse than the muddy trenches of France and Belgium. He did pushups in the mud, jumping jacks in the mud, five-mile runs in muddy boots. He stood, knelt and lay in mud for rifle practice. Cold rain dripped from the metal brim of his helmet. He sat at chow in his sodden wool uniform, eagerly scooping up plate after plate of gristly meat and lumpy potatoes, and his naturally thin frame began to fill out He collapsed onto the creaking, musty bunk right after dark and fell instantly to sleep, only to be wakened in icy darkness what seemed like seconds later, by a tinny reveille. He complained along with the other fellows, just to fit in, but secretly he felt as if his real life had finally begun.

Mary Grant somehow got his address and wrote him a letter. One rainy Sunday when he didn’t fell like playing cards with the fellows and he’d already written to his family, he decided to answer, just a few words.

Dear Mary,

Well, you asked what Basic Training is like and I can only tell you that it is work, work and more work. We do exercise and rifle practice from 5:00 in the morning until it gets dark around 6:00 at night. The food is awful, but we work so hard that we are hungry enough to eat plenty of it.

The fellows here are from all over the place. It’s funny that a lot of them feel the same about their hometowns in West Virginia or New York that I feel about the Rocks: it is a fine place to be from, but not to stay in. A lot of us feel like we’d like to see some of the world and have some adventures, and I guess we’re about to do that. We should be shipping out for France around the first of January. I don’t know if they’ll let anyone go home for Christmas or not. I have to admit I would like to come home one last time before we ship out, but we’ll see.

Sincerely,

Norbert Yaggi

He thought he’d walk to the exchange to mail it right away, but just as he was pulling on his boots, Lefty Liguori burst into the barracks. “Guys! Guys! Guess what! The Kaiser just surrendered!” – only Lefty was from the Bronx so he said “the kaisah just surrendahed.”

The barracks suddenly stirred. Fellows dropped their cards, their newspapers, their fountain pens, and crowded around Lefty. “You don’t say!” “Where’d you hear it?” “Kaiser heard we was coming and knew he better give up!”

Nock stayed on his bunk with one boot on, apart from the crowd. Maybe it wasn’t true.

But Lefty yelled over the milling heads. “Sweah to God! I know the guy in the telegraph room. He went to school with my brothah. He told me. The wah’s ovah!”

They were mustered out the very next day, told to line up in their civvies at the quartermaster’s to get their pay for the four weeks and their train tickets home, and hand in their rifles and uniforms. For a bunch of fellows who talked big about being glad to be out of their little hometowns, Nock noted grumpily that everyone except him seemed pretty excited and happy. The guy in front of him, Lester Martin, kept babbling about getting hired back on in the coal mine and marrying his girl as soon as he got back to West Virginia. There was a restless high-spiritedness in the air.

When Nock reached the sergeant’s desk and was handed a ticket to Pittsburgh, he asked, “Um, say…is there any way I could get a ticket to somewhere else instead?”

“What are you talking about? Ain’t you from Pittsburgh?”

“Well, near Pittsburgh, yes, but I was wondering if I could just go somewhere else.”

“You can go any place you want, soldier, but not at the expense of the U.S. Army. You come from Pittsburgh, that’s where we send you back to. Now move along: some other people is anxious to get home. Next!”

They were transported from Fort Dix the same way they’d come in: in the backs of canvas-covered trucks leaking rain. Then came the wait at the station for the train to New York City, from where they would scatter like billiard balls to their various dull homes.

The train to New York was warm, and cavernous Grand Central Station even warmer. The smell of hot, damp wool lay in Nock’s nostrils as he scanned the schedules for the next train to Pittsburgh. Festive red, what and blue bunting hung over his head, and echoing voices formed a constant background roar.

He stared at the schedule without really seeing it, waving his ticket absently. His eyes wanted above the schedule, to the map of the United States. What had the sergeant said? “You can go any place you want, solider.” Just because he had a ticket to Pittsburgh didn’t mean that he had to use it, and he had his four weeks’ pay.

He approached a ticket window. “Can I trade in this ticket to Pittsburgh?”

The clerk stared down his nose at it through half-glasses. “Nope. Military issue. Can’t trade this one in. Sorry, fellow.”

“Well, then, how much for a ticket to…” Nock thought for a second. “California?”

“Where in California?”

“Well, say Los Angeles. Isn’t that where they make the movies?”

“First class or budget?”

“Better say budget.”

The clerk consulted his price list. “Twenty-two dollars.”

“I’ll take it.” Nock pushed two twenties toward the clerk, more than half of his four weeks’ pay.

“Going to be in the pictures, are you?” the clerk asked.

“Something like that,” Nock replied.

“Good luck to you, fellow.”

“Thanks. When’s it leave?”

“On hour from now. 7:00. Track 12.”

“Thanks.”

Nock took his ticket and his change. He’d write to his family from the train. Maybe he’d write to Mary Grant, too, to let her know that he got out of town in spite of the Kaiser, give her a little hope. As he passed a trash can, he dropped the Pittsburgh ticket into it, and kept moving.

Infamy

After I wrote the post about my grandmother a few weeks ago, I remembered this short story that I wrote in 2017 based on her last pregnancy. I always wondered what it must have been like to be expecting a baby in the early, dark days of World War II, so I started writing and the story took me where it wanted to go.

I emphasize that this is fiction. It was inspired by my grandmother’s pregnancy in 1942, but my grandmother, to my knowledge, never had an abortion or even considered one. I also emphasize that the story is not meant to be anti-abortion, nor is it meant as a plea for abortion rights. I simply followed the path where my character took me, and I think the story illustrates the complexities of the issue, based on the fictional experience of one woman.

The photo was taken in 1934, shortly after the birth of grandma’s third child, my mother. This story was published in PIF Magazine in December 2017….

The house cannot hold one more person. Grace and Robert live in this 3-bedroom foursquare with their four children. Robert’s mother Bridget has lived with them since she was widowed in 1931. Grace’s older brother Patrick moved in after the Crash, the same brother who lost an arm in the Great War and used to drive a red Packard up to the house, bearing cigars for Robert and a sterling silver rattle and a mahogany crib for her first baby. In the terrible summer of 1936, her sister Patricia and her husband and two children also lived here, the four of them sleeping in their double-bed set up on the front porch. After a rainy night, Grace would find them curled up on the living room floor and she and Patricia would hang the sheets on the line to dry, but by the end of the summer the mattress was ruined.

They are always bumping into each other, on the stairs or coming out of the bathroom or all getting up from the dining room table at once, so that even her growing belly will be in the way, much less the child itself. Her teenage sons share a bed with Uncle Patrick, and her daughters share with Bridget. When she brushes the girls’ hair in the morning, they smell like their musty, decaying grandmother.

Grace is 42, slack-bellied and graying at the temples. Every day, eight people must be fed on one railroad bookkeeper’s salary. The house cannot hold one more person.

On this December Saturday evening, she has the bathroom to herself. Robert is at his lodge meeting. Patrick is at the bar where he works on Friday and Saturday nights. An old war buddy was willing to hire a one-armed veteran who drinks up most of his pay. She told Bridget that she wasn’t feeling well and asked her to mind the kids. Bridget will sit at the kitchen table and play Hearts with Dotty and Shirley. Donny and Davy will slouch on the living room couch, reading comic books and listening to swing music on the radio. And Grace can do what she needs to do.

She tiptoes into the bathroom with her tools, and turns the lock quietly. She undresses, fills the enema bag with carbolic soap and hot water, lies in the tub.

Her hands tremble. She can insert the nozzle into her vagina, but can’t find the entrance to her womb. Then she finds it but can’t insert the nozzle. Then the nozzle scrapes her cervix. Her hands tremble more. The house cannot hold one more person.

The scraping of the nozzle against the inside of her cervix is nauseating. Her stomach cramps. She squeezes the ball and feels the hot water wash inside her. She squeezes again. She thinks she will vomit. She squeezes again. She is sitting in water now, cold. She squeezes again.

She will have to skip Mass tomorrow, claim illness again. She will have to confess first thing Monday, go to a church downtown, where the priest doesn’t know her. She will do any penance: pray the Stations of the Cross, climb the steps of Immaculate Heart on her knees. The house cannot hold one more person.

The bag is empty, and the bath water is clear, no blood. She dries herself, pins an old diaper inside her pajama bottoms, and goes to bed. She thinks she won’t sleep, but she doesn’t hear Robert come home.

***

The next day is overcast. It might snow.

Grace excuses herself from Mass and asks Bridget to cook lunch, citing severe “woman problems,” which is not exactly a lie. She stays in bed and keeps checking the diaper for blood. When she finds none, she tries to convince herself that it is for the best, that God must want this child to come into the world. But she knows in her heart that she will try again next Saturday, if she gets the chance.

She decides that something might happen if she gets up and moves around. She rises from bed, dresses and goes downstairs to help Bridget wash the dishes and start Sunday night supper. They will have meat pie, made with leftovers from last night’s roast, and some of the peaches she and Bridget canned in August.

Bridget is rolling pie crust with her loose-skinned sinewy arms, and Grace has just come up from the cellar with 3 jars of peaches. The radiators are hissing warmth, steaming the kitchen windows so that it seems they are cocooned from the world outside.

Donny and Davey come banging into the house, the screen door slapping shut behind them. “Dad! Mom!” Donny yells, “Turn on the radio, quick!”

Robert has been sitting in his easy chair in the living room, reading the newspaper and dozing off, as he always does on Sunday afternoons. His newspaper rattles, and he asks sleepily, irritably, “What? Why should I turn the radio on?”

“The Japs attacked Hawaii! It’s on the radio!”

Grace and Bridget sleepwalk, gape-mouthed, into the living room. Dotty and Shirley look up from their Parchesi game. Patrick wanders down from his bedroom, his afternoon nap disturbed. Robert is turning the radio dial. She hears static, and then the urgent, staccato tone of a news announcer’s voice.

Grace finally feels the gluey warmth between her legs and her gaze rests on her sons, bent avidly over the console radio. They are 15 and 17, pink-cheeked from the outdoor cold, irreplaceable.

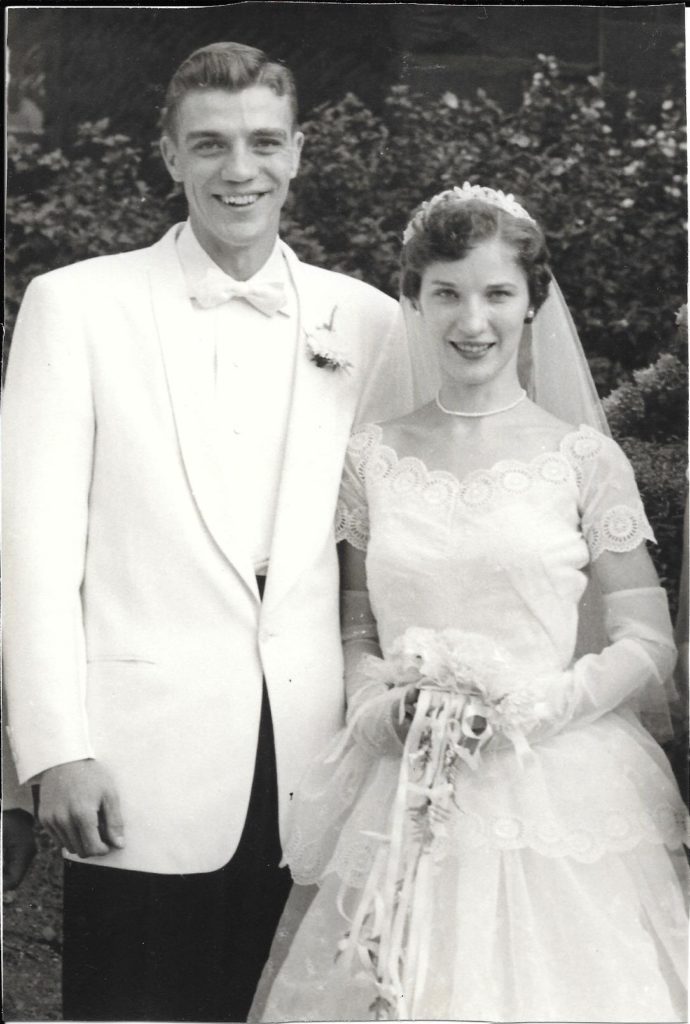

My Kick-ass Flapper Grandma

In my last post, I promised a tribute to my grandmother, Mary Angela Grant Yaggi, whose personality and spirit shaped my own.

Born in 1901, her life spanned nearly the whole of the 20th century. She lived to see the Wright Brothers’ first flight, the first footsteps on the moon and the launch of the Hubble space telescope. She was a young flapper in the jazz age and the harried matriarch of a large family during the Depression. When she was born, her hometown bustled with industry. Her husband toiled over ledger books and a 20-pound adding machine to make a living. By the time she died, her grandchildren carried computers in our backpacks, and McKees Rocks was born was battered, hollowed-out ghost of its glory days.

Early life

Grandma began her life in the Norwood neighborhood of McKees Rocks in September 1901, the oldest of four children of Michael and Margaret Grant.

When she was 12 or 13, her little sister, Roberta, died. Family lore has it that, as she died, Roberta cried out, “Mother! I see Jesus!” Roberta became a sort of family saint (and is my mother’s namesake). Her mother kept the nightgown she died in, and she and my grandmother used to cut little scraps of the nightgown to pin onto the clothing of anyone in the family who was sick.

Mary and her surviving siblings, Helen and Jack, had the kind of childhood that children of railroad laborers in Norwood had in the early 20th century: plain food, homemade clothing, Mass every Sunday and Holy Day without exception. According to the history of McKees Rocks and Stowe Township, the Norwood and West Park neighborhoods were still semi-rural during grandma’s childhood, and many housewives helped feed their families by planting small gardens and raising a pig each year. Grandma never mentioned her mother doing either of those, but I come from a line of doughty little women, so it wouldn’t surprise me in the least.

Grandma grows up

We have several pictures of grandma as a little girl, but I chose the two below to share, because they so perfectly illustrate two sides to her personality. The women in my family love pretty clothes. In the picture on the left, you can see that my great-grandmother was turning Grandma into a fashion plate from an early age. Grandma was the child of a laborer, but her mother made sure she dressed like a spoiled little princess in this portrait of her at age 4. The portrait on the right, taken around the same age but unposed, shows her fierce personality. She’s the barefoot little girl on the right with the I-WILL-see-the manager-this-instant look on her face. Like me, grandma was a classic firstborn: opinionated, determined and bossy, from toddlerhood to dotage.

Fashion plate right from the start.

DO.NOT.MESS.WITH.MARY.

As she matured, grandma’s interest in beautiful clothing grew. In the photograph below, she felt very proud of the fur-trimmed coat she was wearing. She must have sent the photo to someone because she typed on the back, “I don’t want you to look at the face, just the coat.” The photo probably dates to about 1919, when grandma had finished school and started earning her own money. She took advantage of her new freedom and income to do herself up as the Zelda Fitzgerald of McKees Rocks. I remember her bragging about being the first girl in the Rocks to bob her hair and wear short skirts with unbuckled galoshes. Yes, that was a thing; see this New York Times article from 1922.

The young Mrs. Yaggi