This is a slightly modified version of an article that appeared in the Spring 2024 issue of The Ceilier, the newsletter of the Pittsburgh Ceili Club.

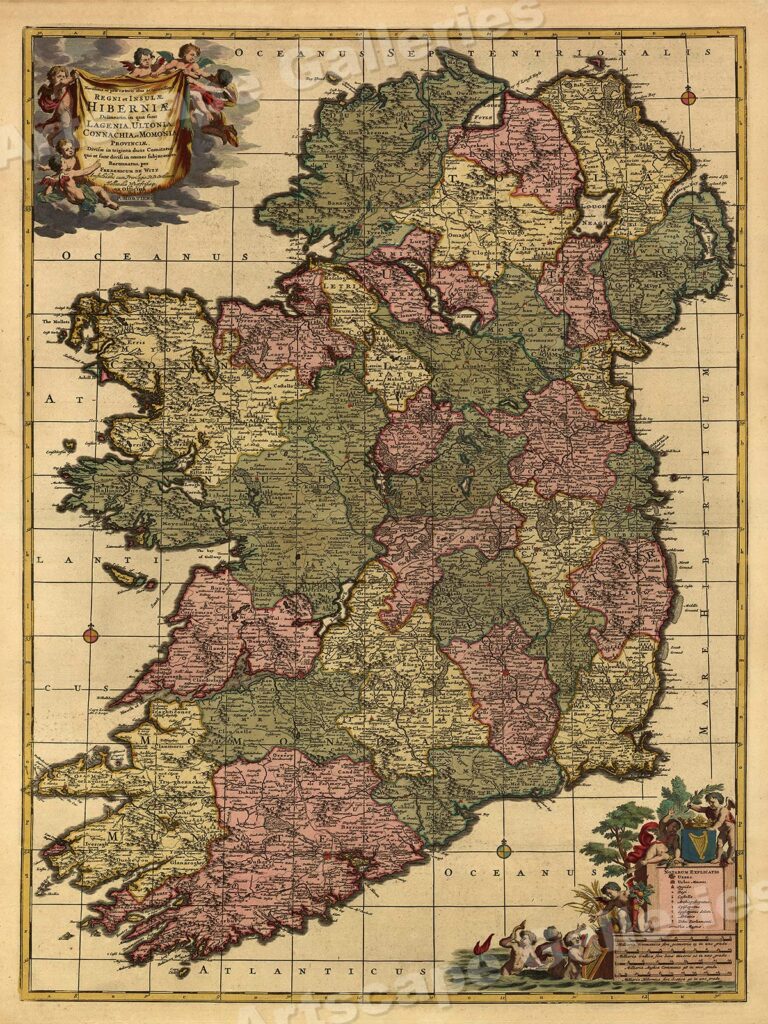

Early Irish Immigration

The first Irish in Pennsylvania were small numbers of servants, trappers and traders in the eastern part of the state.

In the late eighteenth century, they started coming in larger numbers. In the first U.S. census in 1790, the population of Pittsburgh was already 19% Irish. Over 250,000 came from Ulster alone in the eighteenth century. Both Presbyterians and Catholics, they sought economic opportunity and escape from British Anglican religious tyranny. Until the 1840s, they were mostly Protestants and tended to be skilled craftsmen, shopkeepers, soldiers and landed gentry. Many laborers on the National Road and the Pennsylvania Canal were Irish. Others were among the early settlers who pushed the Pennsylvania frontier west to Pittsburgh. The Irishman George Croghan established trading posts north of the Ohio River by the 1740s.

And, of course, they brought their music. The dances of the western Pennsylvania frontier in the early nineteenth century were the same reels, jigs, hornpipes and country dances that were found in Ireland. The roots of Appalachian music lie in Ireland and Scotland.

The Potato Famine and Nineteenth Century Immigration

The potato famine of 1845-6 impacted both the character and the volume of Irish immigration. Starting in the mid-nineteenth century, most of the immigrants were Catholics. A million and a half Irish migrated to the U.S in 1845-6. Between 1851 and 1921, 3.7 million more came. By 1900, there were more Irish in the U.S. in Ireland.

Even after the famine, people had many reasons to migrate. The linen trade in Ireland was in decline. Rents kept going up. Only oldest sons could inherit a family cabin and land in Ireland, so younger sons tended to look elsewhere for opportunities. Many women left because they didn’t have dowries to offer, and therefore their marriage prospects were poor at home.

The men took work as unskilled laborers, digging ditches or toiling in iron and steel mills. Similar to immigrants today, they often died doing dangerous work that the native-born Americans didn’t want to do. They dug canals, laid railroad track, poured molten steel. Girls were domestic servants. Women saved their money to gain independence and to send money home to family in Ireland. More single Irish women migrated to the U.S. than any other ethnic group.

Hardship and Discrimination

Sometimes called “America’s first ethnic group,” the Irish pretty much invented what we today call “chain migration.” Many of them sent money back home to fund the migration of relatives.

Also like many of today’s immigrants, the early Irish imiigrants faced discrimination. Female domestics were disparagingly called “Bridgets,” the equivalent of calling a Black female servant “Mammy.” Native-born Protestants suspected the Irish of being more loyal to the Pope than to their new country. When jobs were posted, the signs often read “Colored and Irish need not apply.”

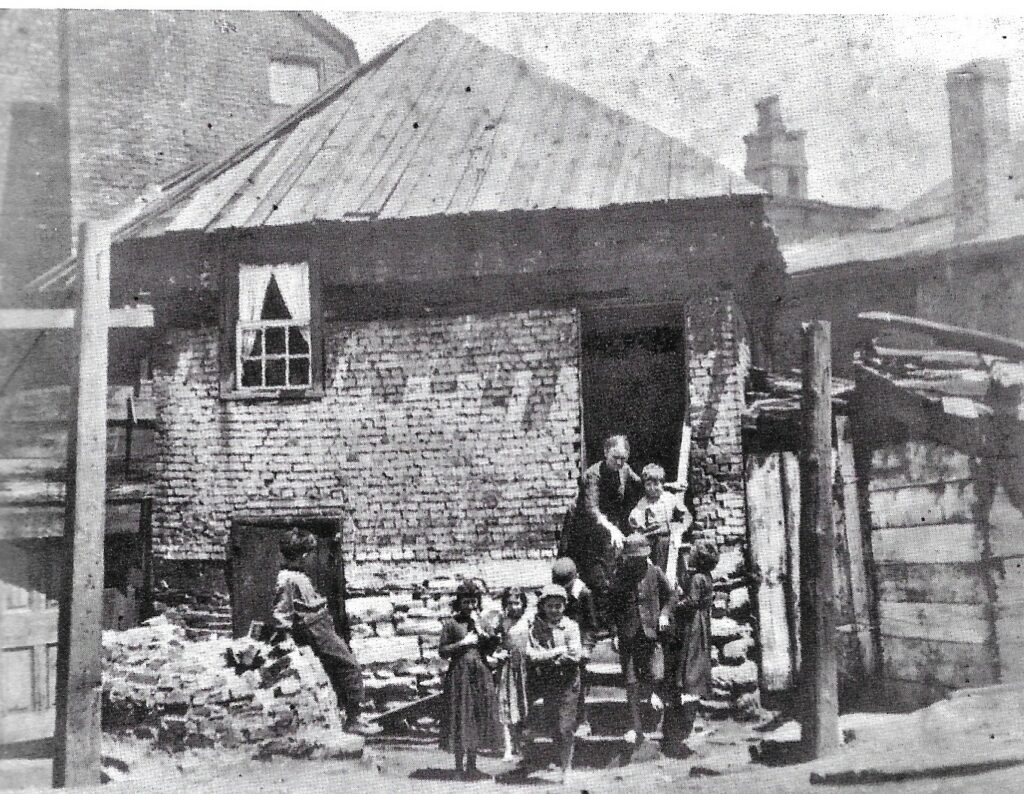

In Pittsburgh, the Irish settled in in shantytowns in the Hill District, Lawrenceville, Homewood, Hazelwood. They were also found in a South Side neighborhood called Limerick, the current location of Station Square. The Point neighborhood in downtown Pittsburgh housed so many Irish that it was called “Little Ireland”. In his book Pittsburgh Irish, Gerard O’Neil tells a lovely little story of an Irish woman named Sibby Powers who ran a small store out of her apartment – which happened to be on the first floor of the old Fort Pitt blockhouse. She sold mostly candy and little cakes, along with a few small necessities like needles and thread. She placed her wares on shelves in her window, so that customers could see what was on offer. Mayor David Lawrence remembered buying candy from her when he was a child.

Coming mostly from rural areas, the immigrants to these close-packed slums were exposed for the first time to cholera and smallpox. Separated from their loved ones and facing hardship and discrimination, they also suffered from alcoholism and other mental illnesses. Naïve new immigrants were often fleeced of what little money they had by unscrupulous land agents or bogus employment agencies. Industrial accidents, crowded housing and lack of sanitation led to high rates of mortality. Many widowed young mothers had to take in laundry or do piecework at home. The Irish tended to have many children, born close together – hence the phrase “Irish twins.” But the child mortality rate was high. Large numbers of children died from premature birth, respiratory disorders, diarrhea, poor nutrition, smallpox, measles and diphtheria. Civic groups like the Ancient Order of the Hibernians, Knights of Equity, Christian Mothers and Sacred Heart Society arose to help.

Rising to the Challenges

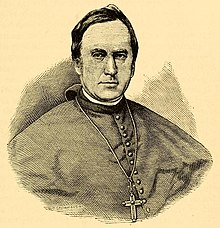

The Catholic Diocese also paid a large role in helping the new Irish-Americans to survive. Saint Patrick’s Church in Strip was the first Pittsburgh parish, founded in 1808. The first bishop was Michael O’Connor (1820-1872). Born in Cobh in County Cork in 1820, he was appointed Bishop of the Diocese of Pittsburgh in 1843. He brought with him eight seminarians and seven Sisters of Mercy. During term as Bishop, the number of Catholic churches and clergy steadily increased. He founded the Pittsburgh Catholic newspaper, St. Michael’s seminary, a hospital, a girls’ academy and an orphanage. The Sisters of Mercy founded Mercy Hospital in 1847, the first hospital in downtown Pittsburgh. They treated all patients in need, even if they couldn’t pay, during outbreaks of smallpox, cholera and typhus.

As the numbers of Irish swelled, over time most Irish who came here started out living with relatives already here, which helped both parties.

By the end of the nineteenth century, the Irish in Pittsburgh were thriving. In the nineteenth century, child labor had often been a necessity for Irish families. By the twentieth, most children could be kept in school.

Irish women no longer confined themselves primarily to domestic work. Now, they found work as nurses and teachers. The men were railroad workers, skilled laborers, clerks, and owners of small businesses. In 1906, George Clinton Murphy founded G C Murphy stores, headquartered in McKeesport. Eventually, he had five hundred stores in twenty-six states. Many Irish also served as police officers or firefighters or held government positions.

The Irish were key figures in the labor movement of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Irish priests like Charles Owen Rice (1908-2005) and labor leaders like Philip Murray (1886-1952) fought for worker’s rights. Murray had been a coal miner. His family was evicted from their company housing for inspiring a strike. Later, he became the president of the Steel Workers Organizing Committee and the United Steelworkers of American and president of the Congress of Industrial Organizations.

Pittsburgh Irish in the Twentieth Century

As the Irish in Pittsburgh strove and succeeded, they also entered politics. Pittsburgh has had several Irish mayors, including Pete Flaherty, Tom Murphy and Bill O’Connor.

Starting in the mid-twentieth century, many Irish people were so prosperous that they travelled back to Ireland to visit relatives, or brought relatives here to visit with them. This was also the era of resurgence of interest in Irish Heritage. In Pittsburgh, the second half of the twentieth century saw the creation of the Irish Centre, the Ireland Institute, the American Ireland Fund and the Irish Festival. The Echoes of Erin ratio program started during this era, as well as the Irish Rowing Club, Pittsburgh Irish and Classical Theater, the All-Ireland Athletic Club, the Gaelic Arts Society, and the Pittsburgh Ceili Club. Irish stores, and Irish pubs like Mullaney’s Harp & Fiddle, sprung up.

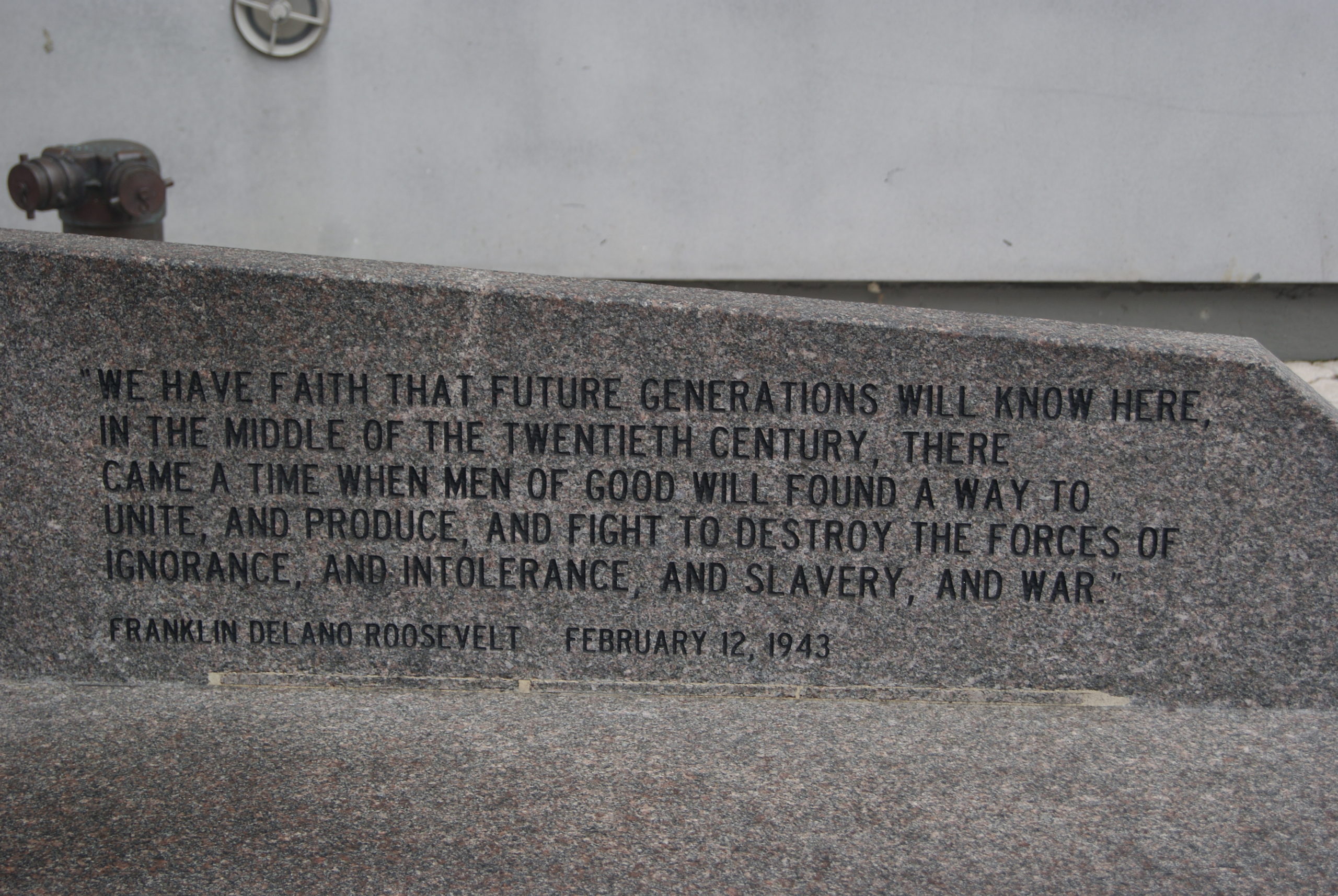

The Irish are rightly proud of our heritage in the United States. And our forebears’ story is the story of America. The story of brave, desperate people who leave behind everything familiar to make a better life for their families. People who demand to make their contribution, in spite of hardship and discrimination. It’s still happening today. And it’s part of what makes our country great.

Sources

McElligott, Patricia. Irish Pittsburgh. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2013.

O’Neil, Gerard. Pittsburgh Irish: Erin on the Three Rivers. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2015.