Have you ever driven between Pittsburgh and Ohiopyle State Park? Then you’ve travelled one of the oldest roads in the United States and our nation’s first federally-funded highway.

Today’s US 40 was, in the early nineteenth century, The National Road, an important route for traders and settlers. Conceived by Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin and built between 1811 and 1818, the 600-mile National Road started in Cumberland, Maryland. It then crossed present-day Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Ohio, and Indiana, before arriving at its terminus in East St. Louis, Illinois.

You can still drive the whole length of the road today. We may do that someday, but, for now, Al and I decided to drive just the Pennsylvania section. Today’s blog post covers the eastern section of the road between Addison and Confluence. Future posts will cover other sections of the road.

Addison

We started on a snowy January day in Addison, PA, near the Maryland border. Long before the arrival of white people, Indians hunted along the nearby Youghiogheny and Casselman Rivers. Signs of Indian encampment and burial ground exist on Fort Hill, but there is no evidence that a fort ever stood there. The earliest white settlers named their little town Turkeyfoot. Later town leaders renamed it Peterburg after Peter Augustine, who laid out the town.

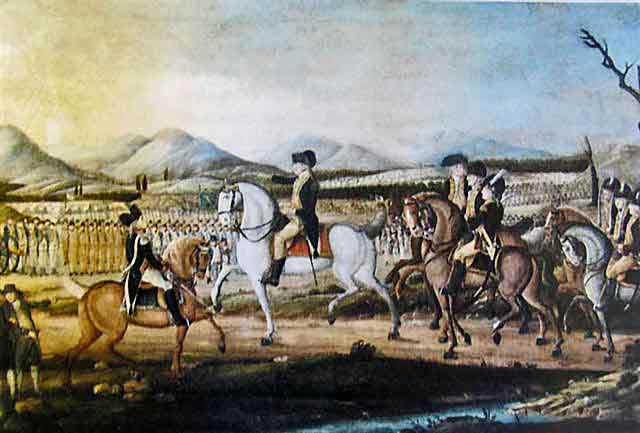

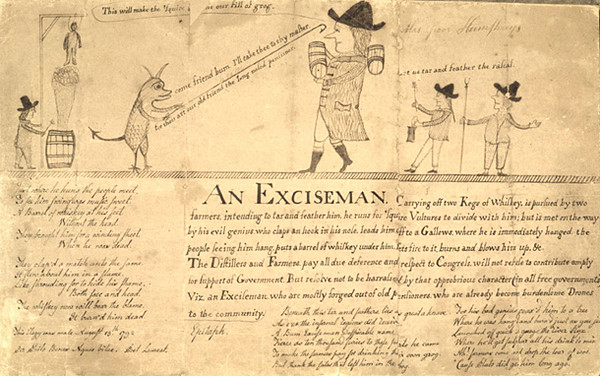

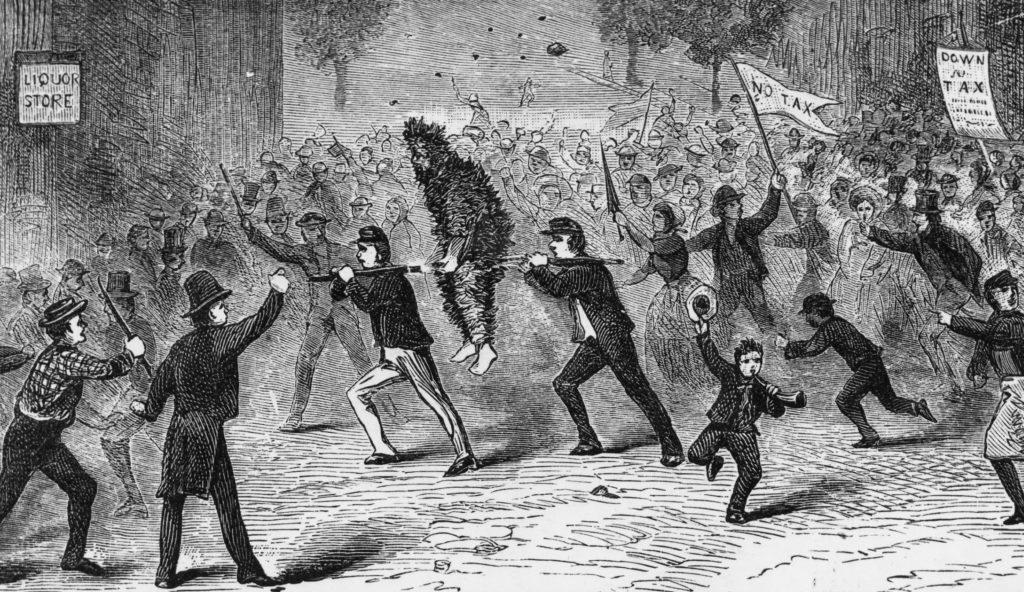

Six thousand Federal troops camped out on Augustine’s farm in Addison in 1794, on their way to stop the Whiskey Rebellion. Augustine himself was Whiskey rebel, so the troops apparently didn’t feel much remorse about eating his produce and trampling his fences. The Augustine family sent the government a $500 invoice for damages. It was never paid.

The town’s name changed one more time, in 1831 when it was renamed Addison, after Judge Alexander Addison. Ironically, Judge Addison had defended the law during the 1791-4 Whiskey Rebellion. So, the renaming of the town was another, posthumous defeat for the Whiskey rebels.

The Addison Tollhouse

Addison is a tiny town, with a pretty little park across the street from its main claim to fame: the Addison Tollhouse. The toll house dates to 1835, when tolls were first collected on this part of the road. It has been rebuilt and repaired to reflect its 1835 appearance.

A sign hung on the tollhouse wall shows the 1835 toll rates: twelve cents for a chariot or stage coach, four cents for a horse and rider, six cents for every fifteen hogs, and so on.

The town is also known for its National Chainsaw Festival every year in June.

Nearby Pumers Pub looked to have a good menu, and we hoped to get some lunch, but it was closed – apparently due to the pandemic – and we were freezing, so we got back into our car.

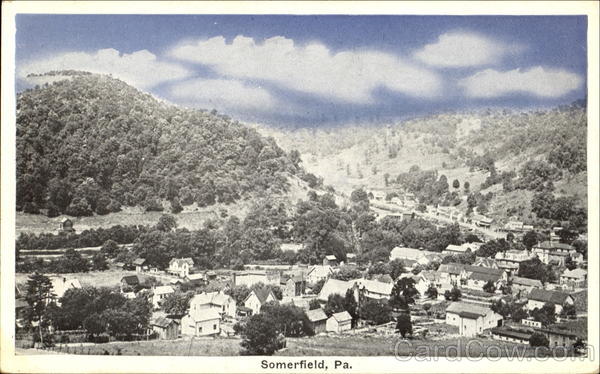

Somerfield

Our next stop on the old National Road was the Somerfield Dam and Bridge, a few miles west of Addison on Route 40.

The drowned town of Somerfield had an interesting history. Like most of Western Pennsylvania, the area was originally inhabited by the Monongahela people. Later, the Shawnee, Seneca, Delaware and Erie camped and hunted there.

In 1753, George Washington and Christopher Gist crossed the Youghiogheny about half a mile upriver from the future site of Somerfield. Washington was on his way to warn the French to vacate southwestern Pennsylvania. The ignored warning led to the French & Indian War, and in 1755 General Braddock also forded nearby on his march to Fort Duquesne.

White settlers started to arrive after the Fort Stanwix treaty of 1768. One of the first settlers in what became Somerfield was Jacob Spears. Spears bought a piece of riverfront land on the east side of the Youghiogheny in 1789 and named his homestead Nobbley Nowl (or Knobby Knoll).

The National Road Comes to Somerfield

The construction of the National Road brought the first bridge to Somerfield. Great Crossings Bridge, a three-arch stone bridge, commemorated Washington’s and Braddock’s crossings. The bridge was dedicated on July 4, 1818, with President James Monroe in attendance.

Also present at the dedication of the bridge was Philip Smyth, who had bought out Jacob Spears and renamed the town Smythfield. The name of this town also changed later. In 1830, the town applied for a post office and discovered that there was already a Smithfield post office elsewhere in Pennsylvania. They renamed the town Somerfield in honor of a local reverend.

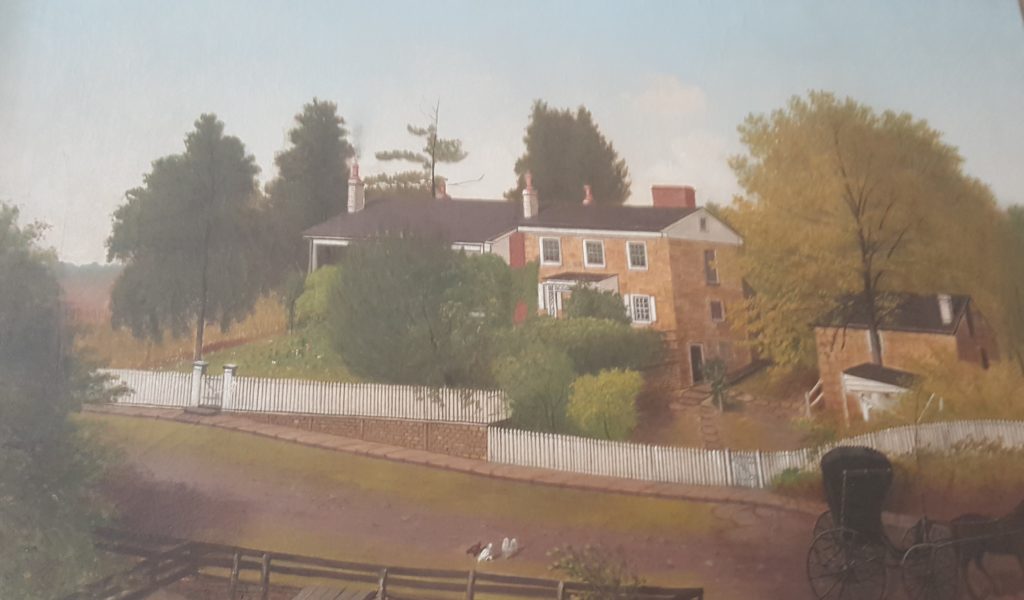

The National Road brought prosperity to the little river town. Drivers needed to change horses every 10-12 miles when travelling over the mountains, and we saw the remains of many relay stations along Route 40. Somerfield was home to one of these: a stone tavern with an inn and stables,

built by the bridge contractor, Kinkead. A Virginia tavern keeper named Thomas Endsley bought the tavern from Kinkead in 1823, and apparently ran it with the help of eight enslaved people he brought with him from Virginia.

The National Pike declined with the coming of railroads, and Somerfield declined along with it. By the 1880s, only 80 people lived in the town.

The Drowning of Somerfield

But, as the railroads take, so they also give. By the early 20th century, a rail line came through and Somerfield began to grown again. The town transformed itself into a resort area for sportsmen: fishermen, hunters, boaters. President William McKinley spent six weeks in Somerfield each summer. He had relatives in the area, including a niece, Mabel Mckinley, who later became a renowned singer and composer.

Somerfield’s next change of fortune was less lucky. In the 1930s, local governments and the Army Corps of Engineers became concerned about flood control along the Youghiogheny. The Corps determined that the river should be dammed. Somerfield would be drowned by the river that had first given the town its life.

The dam and bridge project started in 1939, halted temporarily during World War II, and finished in 1946. By then, Somerfield had been torn down and all 142 (some sources say as many as 176) residents relocated.

A new bridge spans the lake today, and new marinas, camp grounds and inns house our century’s sportmen and their boats.

But in dry years, when the Youghiogheny Lake is especially low, the foundations of Somerfield’s houses and the remains of the old three-arch stone bridge re-emerge like ghosts.