Our final drive along the National Road took us through Indiana and Illinois, where we learned that flat, fertile farmland plus a road added up to prosperity, at least in the nineteenth century.

Our first stop in Indiana was the Welcome Center in Richmond. Angel Groves, their Communications and Social Media Specialist, was very helpful when we told her that we were travelling and writing about the whole road. The Welcome Center offers a great deal of informational material, most of it free.

Centerville

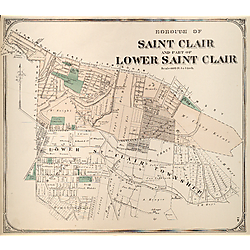

The theme that emerged during our drive through Indiana was prosperity. The main street of Centerville, our next stop, exemplified that theme. The little town is very well-preserved, lined by a magnificent nineteenth-century library building, antique shops and other small businesses.

Similar to Morristown, Ohio, plaques mark many of the buildings, indicating the year that they were built and the name of the original owner. Many buildings were former taverns and inns, and feature the original covered archways that guests used to bring carriages to the stables in the rear. Centerville is also home to the restored house of Oliver P. Morton, Indiana’s Civil War era governor.

Cambridge City

Just outside Cambridge City lies the Huddleston Farm House, constructed in 1841. Huddleston was a pretty smart guy. He intended to farm his land, but recognized that farmers often need a supplementary income. He situated and designed his farm house to also serve as a place where travelers could rest and buy provisions. The ground floor of the three-story house featured two rooms with outside entrances. Twenty-five cents a day bought shelter and a fireplace to cook your own hot meal. For an additional fee, Huddleston stabled and fed animals and provided meals. The building and grounds are open for tours on a limited basis.

In Cambridge City itself, we discovered more well-preserved architecture and had a great lunch at Kings Café and Bakery. At Kings, we also sampled Indiana’s state pie: sugar-and-cream pie. Delicious! We picked up the recipe, but that recipe didn’t work out for me. So, I’m now on the lookout for a better sugar-and-cream pie recipe. If I find one, I’ll publish it. I’d never heard of sugar-and-cream pie before, but it is definitely a treat not to be missed.

Decline and Rebirth

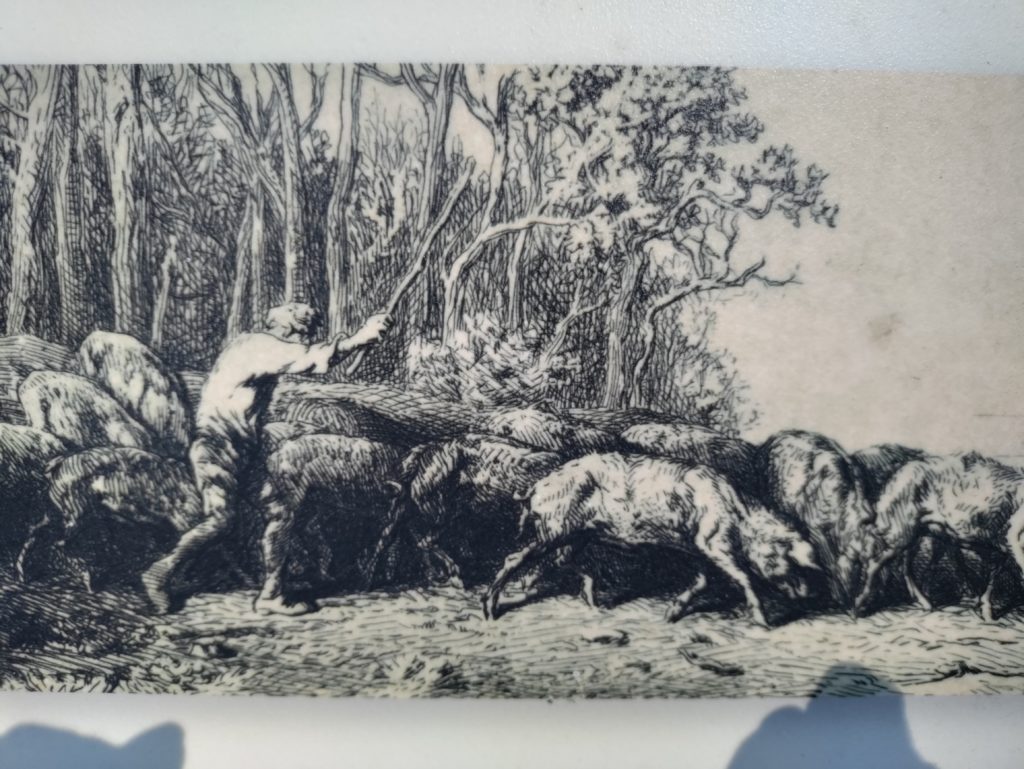

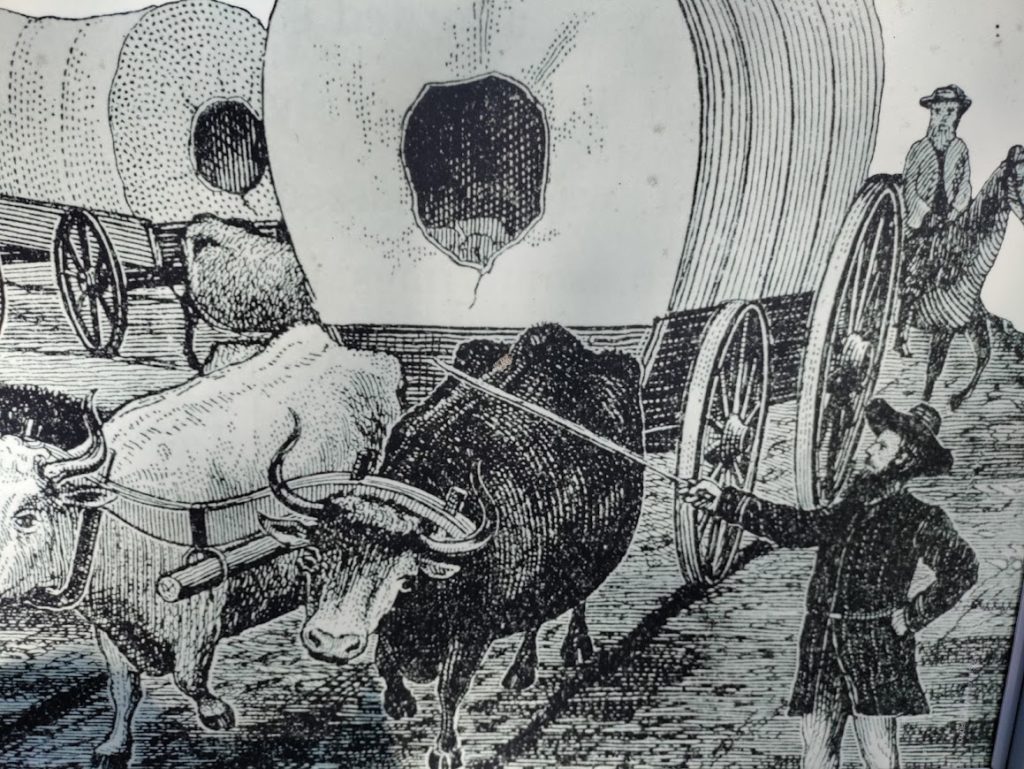

Boom and bust is the way of capitalism, and so it was with the National Road in Indiana. Imagine traveling on a rainy fall day, with mud up to the carriage’s axles, every bone in your body aching from bumping along the rough gravel road. Imagine sharing that road with farmers herding cattle, hogs and geese. Hog drovers were such a problem that they are the origin of the term “road hog.”

Now imagine that railroads start to span the Midwest, as they did in the 1850s. The railcars are enclosed. The ride is smooth and fast, with no impediments by livestock. As the railroads advanced, traffic on the National Road declined. The prosperous little towns faded, and some disappeared completely.

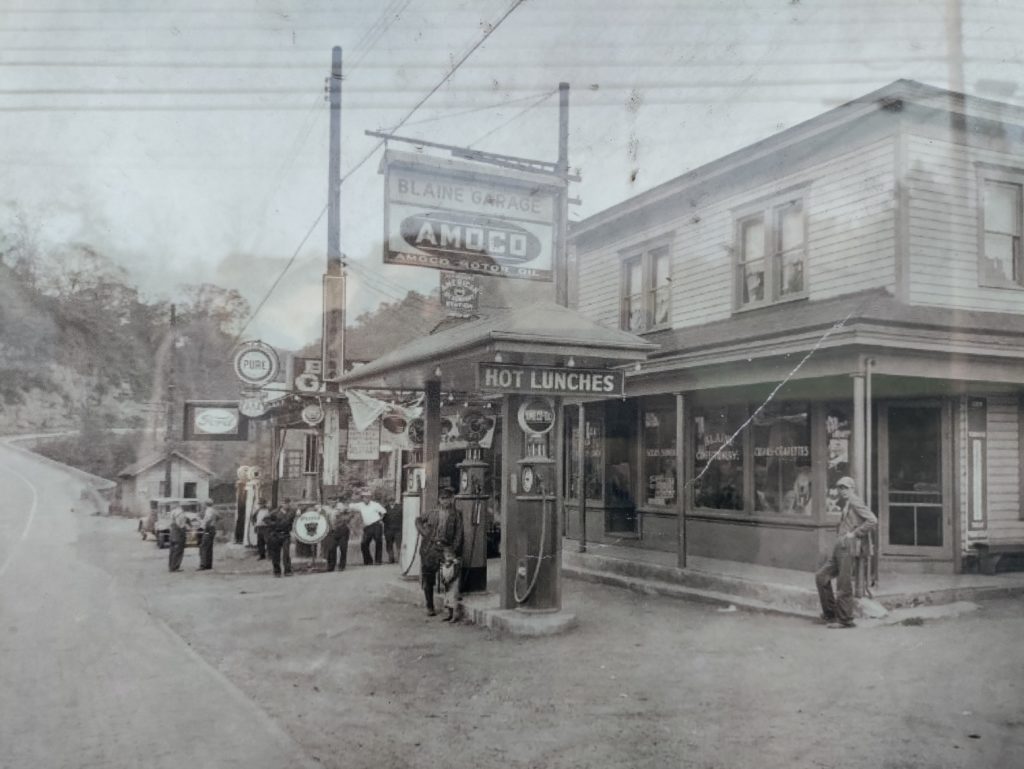

The Road was reborn in the 1920s, as automobile traffic grew. Farms like the Huddlestons’ started renting camping space to motorists. Gas stations, diners and motels replaced taverns, blacksmiths and wheelwrights. You can still visit the Twigg Rest Stop, an early version of the rest stops that stand along every major highway in the United States.

The Studebaker blacksmith shop in South Bend was an Indiana business that prospered greatly from the dawning automobile age. The blacksmith shop became Studebaker Manufacturing in 1868, primarily making wagons. In the early twentieth century, the company pivoted to motorized vehicles. They built their first electric car in 1902, and their first gas car in 1904, the only manufacturer in the United States known to successfully transition from horse-drawn to gas-driven vehicles. Studebaker prospered until the 1960s. Manufacturing in Indiana ended in 1963, and last Studebaker was made in Ontario in 1966.

Other Indiana Highlights

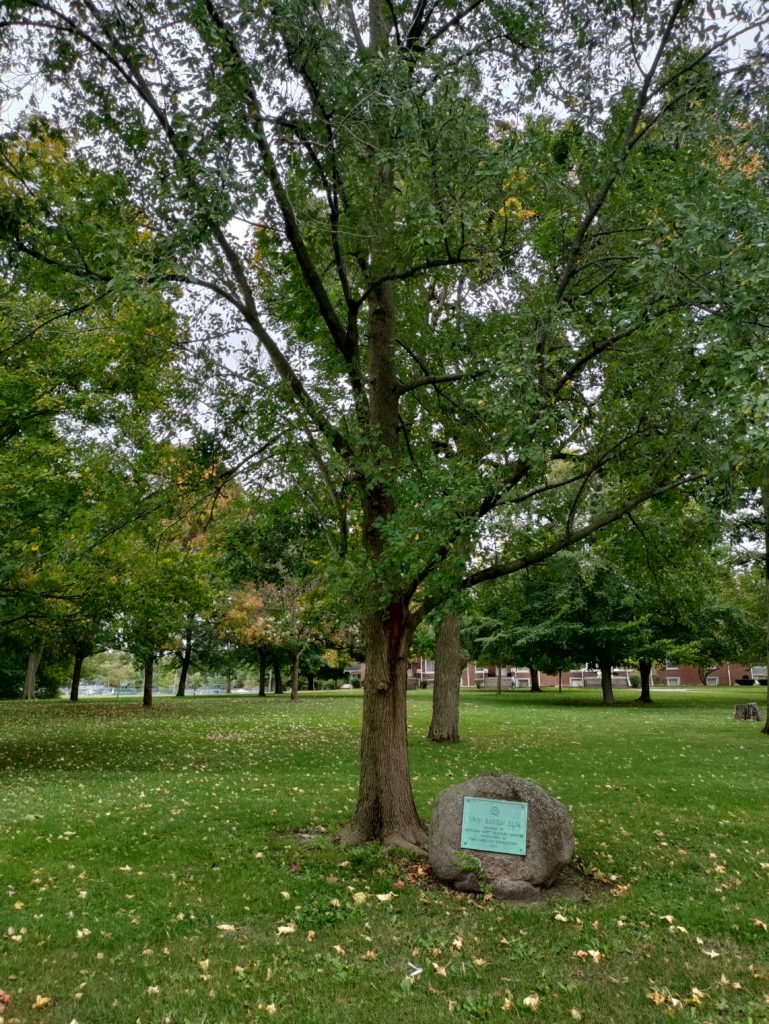

On our way out of the state of Indiana, we also passed a recently-discovered one-room log cabin from the National Road era, and the Van Buren Elm. In 1842, at the site of the elm, President Van Buren’s carriage overturned, sending him into the mud. One story claims that the accident was staged, to change Van Buren’s mind about his opposition to using federal funds to improve the National Road.

We also stood on a surviving 1920s gravel section of the Road, running parallel to the current road, near Putnamville.

The National Road in Illinois

Illinois doesn’t do as good a job with the National Road as Ohio and Indiana. But we did enjoy our stop at the terminus of the Road in Vandalia. Vandalia was the capital of Illinois from 1819 until 1839, and the old statehouse is very nicely preserved. Abraham Lincoln served there as a state representative from 1834 until the capital was moved to Springfield in 1839.

At the statehouse, in 1837, Lincoln first went on record in opposition to slavery. Although officially a free state, Illinois was sympathetic to slavery. Many Illinoisians were transplants from the slave states of Kentucky and Tennessee. In Lincoln’s time the state also still allowed indentured servitude. Indentures could last as long as 99 years, and the owner of an indenture could pass it along to his heirs.

In 1837, in an act of moral support with no real consequences, the Illinois state legislature passed a resolution condemning abolition societies. The resolution also included the opinion that slavery could never be abolished in Washington, DC, without the consent of its citizens. Lincoln and another legislator, Dan Stone, objected to the resolution.

Slavery remained legal in our nation’s capital until April 16, 1862, when it was abolished by executive order by President Abraham Lincoln.

The End of the Road

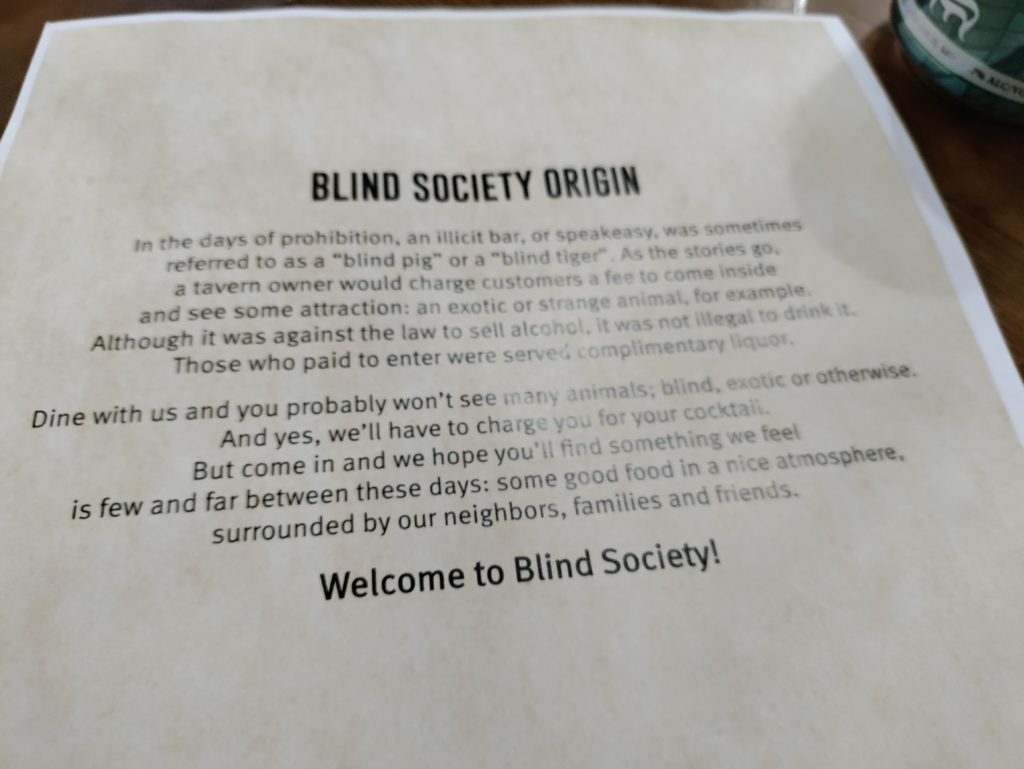

We ended our time on the National Road with an excellent dinner at The Blind Society in Vandalia. The restaurant shares space and ownership with Witness Distillery, a local bourbon distillery. The owners happened to be in the restaurant the evening we visited, and Al, a big bourbon fan, started a conversation with them – and we ended up with a free bourbon tasting. A wonderful ending to our very enjoyable and educational drive along our country’s first infrastructure project.

Sources

Most of the information in this post comes from the excellent signage placed at significant historic sites along the National Road in Indiana and in Vandalia Illinois.