After I wrote my March 26th blog post about French & Indian war sites along the National Road, I remembered a story that I wrote twenty years ago and never published. It imagines a young soldier in Braddock’s fateful double-crossing of the Monongahela River in the summer of 1755 . . .

July 9, 1755

One year and eight months to go

The trees loomed in endless columns like an army of their own, on both sides of the narrow trail. An occasional languid breeze ruffled their very top canopy, but the humid forest was otherwise still on either side of the long, slow-moving line of soldiers, animals and wagons. The chirping whirr of locuts suddenly rose and fell, as if shrieking a warning.

Jamie’s boots trampled last fall’s leaves to dust and occasionally thunked awkwardly against rocks on the trail. Twigs snapped and leaves rustled, as they snagged on woolen sleeves. Wagon wheels creaked wearily as they had for the last one hundred miles and thirty-one days, up and down one tree-blanketed mountain after another, across rivers gurgling over ox-sized rocks bearded with black moss. Thin blades of light lent a white glow to a spot of fern-carpeted woodland floor. The army Jamie marched with had traveled the dim forest from Fort Cumberland, Maryland, to this dense, humid Monongahela River valley, claimed by the Penn family the Colony of Virginia, and, not incidentally, by King Louis, whose French soldiers and their Indian allies were sparsely entrenched in a small fort on a point of land where the Monongahela met the Allegheny.

This 1200-man army had been sent to dislodge that stubborn little outpost.

Jamie Grant, aged 18, short and broad-shouldered, scarred by smallpox, was the youngest son of a cottar family of the Scots lowlands and more recently the indenture of one Daniel Hamilton of Alexandria, Virginia. He knew little about the politics of the territorial dispute and cared less. Jamie marched toward the front of the column with the other blue-coated British colonial road-builders for a single reason: after two years’ service, and assuming that he survived and assuming that the French and their Indian allies could be dislodged, he would be entitled to fifty acres of land of his own. The British would allow him to keep his hatchet, his knapsack, his blanket and his gun, and whatever of his pay he could set aside, and start his own life as a land-owning man.

He had one year and eight months to go.

Jamie kept this thought firmly in his mind throughout the long days of clearing trees, hauling rocks to swampy patches of trail, and marching, marching, marching, mile after steep, forested mile. It kept him moving and it kept him from marrying about the Indians.

Ever since they’d entered the Monongahela valley, the army had been intermittently harassed by an enemy that seemed to emerge from nowhere, strike swiftly and then return to nowhere The column would find itself pelted by rocks for a few minutes. Supplies or horses disappeared in the night. Men learned not to stray from the main column, lest their scalpless bodies be found a few days later on the trail.

But Jamie resolutely turned his worries to something else. When he got his land, how would he know what to do? How did you make sure no other man could claim it? How did you commence taking down all the trees? Who cold tell you how to build a cabin? What did you do for…

“Jaysus Christ” screamed Ian MacIsaac in front of him, as an object dropped from a nearby tree, bounced off his shoulder and tumbled to the ground at his feet.

Distracted by the rustling above them in the tress, Jamie almost tripped over it before jerking back in horror, gasping. It was the scalped head of one of the unit’s stragglers, staring through crusted blood with still-panicked eyes.

Not death but capture

The mood was subdued when they settled down for the night. Jamie, MacIsaac, Mike Miller, and Dan Boone huddled near each other, sleepless.

“They want us to know they’s out there, that’s sure,” Boone remarked.

“Well, we know,” said MacIsaac.

Boone laughed. “You sure was a sight trying to wash that blood off your face and your jacket.” He imitated his friend, flapping at his face and squealing in a high-pitched voice, “Oooo! Oooo! Get it offa me!”

MacIsaac blushed and clenched his fists. “Easy for you to laugh! You wasn’t the one had a head fall on you!”

“Admit it,” Miller needled, “you’re scared of the Indians.”

“Hell, yeah, I’m scared,” MacIsaac replied, “and so’s anyone with any sense. I heard they cuts the eyelids off the ones they catch. And then you’re lucky if they kills you quick by hacking off your scalp. Some they burns to death, only they don’t do it quick. They takes their time, poking your skins with hot sticks, then when they finally sets you on fire, it’s a slow, roasting fire that kills you real slow. Hell, yeah, I’m scared.”

Miller enthused, “I’m ready for them. Remember that rabbit I shot back by the Yoxio Genhi? Right between the eyes at fifty feet! Just let some Indian try and get a jump on me.”

“That weren’t no fifty feet,” MacIsaac objected.

“And it weren’t right between the eyes, neither,” Boone pointed out.

“Okay, then, but I got it, and it was too fifty feet – or pretty near. You was there, Jamie. That was forty feet sure, weren’t it?”

“Yeah, I’d say forty,” Jamie agreed absently. He had avoided participating in the conversation because he didn’t want Boone and Miller to know that he was afraid. Secretly, he agreed with MacIsaac. The great fear that kept him awake at night was not death but capture. Thus far, the French and Indians had done no more than harass the long column and pick off a few stragglers. But everyone knew that the next day would be critical.

To avoid the obvious attack point of the narrow valley on the north shore of the Monongahela, General Braddock planned to make a double crossing: ford the river at a shallow point before the valley and re-cross at another ford to the west, beyond the dangerous cleft. The crossing points were the times when the army was most likely to be attacked.

Tension in the company had grown in the past few days, as the crossing neared.

“Yep, we’ll be crossing the Monongahela tomorrow,” Boone reminded them needlessly.

“Some’s saying the General’s making a mistake,” Miller whispered. “They’s saying we should take our chances with the ravine instead of taking the time to cross the river twice.”

“I think the General knows what he’s doing,” Jamie said.

Boone shrugged. “Maybe and maybe not.”

“We’d be sitting ducks in the middle of that river,” Miller whispered.

“Well, I don’t think the British Empire got made by idiots making bad decisions. We got an Empire because our Generals know how to fight, and I aim to do exactly what I’m told tomorrow and stay alive,” Jamie said. “And, now, I aim to get me some sleep.”

He lay down on his coat and turned his back to his friends. But he lay sleepless for a long time. He wondered if he would be brave tomorrow. He wondered if he would live.

This army’s in a panic

Miller was wrong. They made both crossings in complete safety the next day. Jamie felt a euphoric sense of relief, as if a huge burden had been lifted. His sodden wool uniform felt light and the road to the forks of the Ohio might as well have been ten feet wide and as flat as your little sister’s chest. He felt that he could run to Fort duQuesne.

Even the immense trees looked friendlier, like guardians instead of jailers. The splayed branches of hemlock and glossy leaves of mountain laurel reached into the trail like welcoming hands.

Jamie heard the ululating whoop and the crack of gunshot at the same second. The column stopped suddenly, clumsily, men tripping over each other as bodies fell in front of them.

Then the whoops and the gunfire surrounded them. Jamie heard a wet thud and a grunt, felt himself splatted with warm liquid and saw Miller fall to the ground beside him. He stared, paralyzed, for a mere second. Then, several of the blue-coated colonials run into the brush along the trail and Jamie’s instinct took him right behind them. He flinched and squeezed his eyes shut as a bullet cracked into the tree beside him.

Okay, okay, okay, just do what the officers taught you. Do what you practiced. Oh God, oh God, oh God, please help me.

With shaking hands, he groped in his box and drew out a cartridge. He brought it to his mouth and bit the end off. Trembling so much that half of it spilled, he poured a little powder in the pan and flipped the cover back over the pan, then hastily withdrew his ramrod and shoved the rest of the cartridge into the barrel of his musket. He tossed the ramrod aside, and pulled his musket up. But what to fire at? He could hear the attackers, but couldn’t see them. They were hiding, damn them! This was no way to fight. How could he get a shot if they wouldn’t show themselves? He squeezed his eyes shut again and blindly fired in the general direction o the high-pitched, staccato war whoops.

His heart was pounding and he was shaking from head to foot. He didn’t think he’d hit anything. He took a deep breath, reached back into his cartridge box and repeated his loading procedure. Damn! He’d thrown aside his ramrod! Where was it? He frantically scanned the fern-covered ground around him, then blindly groped through it. Where was that thing? He heard a cracking sound and felt a sharp stinging on his cheek. He raised a hand to his face and it came away covered with sticky blood and small splinters. The tree was shot again, then, not him. The narrow escape gave him courage. He twisted toward the trail, pulled Miller’s musket toward him, withdrew its ramrod and swiftly and firmly tamped it into his own weapon.

There! A bronzed body popped out of the brush only thirty feet from him, aiming a rifle. Jamie leapt up, raised his musket and fired without aiming, opening his eyes just in time to watch the body fall. I killed him! I killed me an Indian! he exulted and sank to the ground.

He felt a strong hand on the back of his coat and knew a second of panic before recognizing the voice of the British officer in charge of his unit. “Here, boy! Come out of there and fight like a man!” The officer shoved Jamie back onto the trail. “We’re forming a line about a quarter mile ahead. Get there on the double and don’t let me catch you skulking in the brush again or I’ll have you shot!”

Jamie leaned forward as he ran, trying to keep his head below the line of brush. The smell of gunpowder hung in the humid air, and shouted orders were drowned out by the crack of musket fire, the splintering of wood, the thwack-grunt of lead piercing flesh. He leapt over the occasional bloody body, but kept moving until he reached the line.

Incredibly, Colonel Waters was still mounted on horseback, shouting orders to the double line of blue and red coated soldiers, back to back on the trail, each line facing into the forest. Waters motioned him into a position at the end of the line.

“Fire!” Waters shouted, and the lines rose as one and fired into the dense woods. Immediately, fire was returned and Jamie watched several of his comrades sink to the ground. “Reload!” the colonel ordered and James joined his surviving companions in hastily reloading their weapons. “Ready! Aim!”

The men rose as one.

“Fire!”

Blinded by the smoke in the air and the sweat running into his eyes, Jamie pulled his trigger and quickly sank back to the ground. Another dozen or so men fell in a widening pool of blood.

Jamie already had another cartridge in his hand as the colonel raised his arm to begin the reload command. Suddenly, the colonel jerked backward and a burst of blood bloomed on his white vest before he fell, one foot still in a stirrup, body dangling under his panicked horse.

The men on the trail looked around nervously, waiting to be told what to do, but there were no other officers nearby. A few of the men glanced guiltily at their comrades before loping off down the trail. Others dropped their muskets and ran. Jamie held on to his musket and followed them, head down again, frantically butting anyone who got in his way. In his panic, he tripped over a body with its face blown to a featureless pulp, his chin hitting the rock-strewn ground. He picked himself back up and ran on.

He stopped only when he was blocked by a solid wall of read and blue wood coats. From a rise to their left, gunfire pelted down. The bodies were so packed together that men who were hit remaining standing, held up by the living. Jamie saw Boone and MacIsaac in the crush.

He grabbed hold of MacIsaac’s sleeve. “MacIsaac! Come on!” He dragged his friend into the brush along along the path. Boone followed them, swift as a hare.

The three crouched, panting.

“This army’s in a panic,” Boone shouted above the gunfire. “I think most of the officers is dead.”

Jamie wiped his sweaty, blackened brow with a sleeve. “Way I see it, we got only one chance, and that’s to make our retreat in this here brush.”

“But this is where the Indians is!” MacIsaac objected.

“Yeah, and can you see them?”

“No! That’s the trouble!”

“Well, then, they can’t see us neither if we stay along the side. It’s our only chance, MacIsaac.”

MacIsaac squeezed his eyes shut and nodded rapidly.

Boone gave Jamie a steady, appraising look for a second, then nodded once.

A clearing, a cabin and a man

It took the three men more than an hour to fight their way back to the Monongahela River, leaping from the shelter of one tree trunk to another, firing quick, mostly inaccurate shots when an enemy raised his head nearby. They seldom saw the enemy, but constantly heard him in the continuous crack of gunfire and the hideous, wailing war cries.

Finally, Jamie faintly heard the rushing and gurgling of the Monongahela over the waning din of the battle. He turned to MacIsaac and opened his mouth to shout to him, when the Indian came at him.

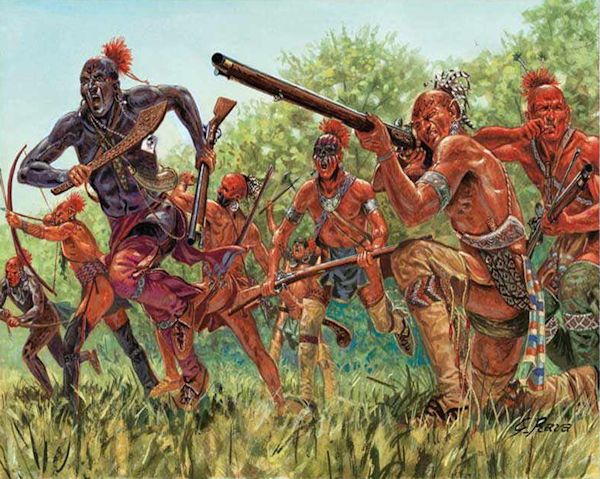

The moment seemed to last forever. Every detail of the man registered vividly in that instant: the hairless bronze chest, gleaming with an officer’s bronze neckpiece, the black-and-white face paint, the feathered earring, the rippling cable of arm muscle, lifting a tomahawk. I’m about to die, Jamie thought as he lifted his musket and fired. When he opened his eyes, the Indian was still coming, a blackened shoulder wound spurting blood, but still brandishing his tomahawk in the other hand. Heart pounding wildly, Jamie desperately shoved the butt of his musket into the man’s chin, then swung it the other way and hit the side of his head with the barrel. He heard a muffled crack as he made contact, and his enemy fell to his knees and then sank face down on the ground.

He glanced around for his companions and saw MacIsaac shoot down another approaching Indian. Boone was grappling desperately with a third. MacIsaac was frantically reloading his musket. Jamie scooped up the dead Indian’s tomahawk and ran at the struggling Boone. Without thinking, he swung the tomahawk down on the Indian’s neck and watched him collapse.

The three friends spun their heads around, but no more enemy approached. “Come on,” Boone yelled, already on the run toward the river.

Within just a few more yards, they slid down a bank to the river, snapping twigs and scattering small rocks ahead of them.

When they reached the river bank, they saw the remnants of the army splashing madly back across the river. Men fell and dropped their guns, scrambled back up and flailed forward some more, only to fall again. A few others dropped one foot in front of the other mechanically, shoulders sagging, guns long gone.

“Jaysus,” MacIsaac whispered.

“It don’t look like they’re being fired on,” Jamie observed.

“Well, then, you for it, boys?” Boone asked, and they began their own crossing.

Early in the dispirited, straggling retreat, few men spoke. Once they were safely away from the river and it was clear that there would be no pursuit, the army camped for the night.

Jamie, Boone and MacIsaac gathered as they had the previous night. They sat quietly for a few moments.

“I saw Miller fall,” Jamie said finally.

“He died right away?” Miller asked. “He wasn’t – “

“He died right away.”

MacIsaac sighed.

“Sure were a botch today,” Boone remarked. “I heard General Braddock’s mortal wounded.”

“So’s most of the officers: dead or wounded,” MacIsaac added.

The three friends were quiet again. I should be sad, Jamie thought. My friend is dead, our army’s beat and now I wonder will I still get my land after my two years is up. Instead, he felt something else. It wasn’t the euphoria he’d felt after the morning’s crossing, when he’d foolishly felt his way to the forks was clear. It was something harder and deeper. He was alive. He’d learned that he was no coward. But there was something else that he struggled to put a name to.

“Seems to me,” Boone said slowly, “them officers and regulars wasn’t much good anyway. The smart ones was the ones disobeyed orders like we did. And that thing we had to do by the river: nobody taught us that in no drill.”

Neither Jamie nor MacIsaac replied to this. But Jamie felt something opening up in his chest. It was a strange sensation, like fear and like excitement, and like seeing a clearing and a cabin and a man.