In today’s post, we go back in time, to before Albert Gallatin conceived our nation’s first publicly-funded road, to a time before we were even a nation.

In the 1750’s, the British, the French and the six nations of the Iroquois Confederacy disputed the ownership of today’s American Upper Midwest. French traders and trappers pressed down on the area from Canada. The Iroquois hunted and farmed. And the British moved relentlessly westward from the Atlantic Coast, seeking land that could be settled and farmed. The three nations lived in a tense state between war and peace. The Iroquois Confederacy played off the two European powers against each other.

All three powers knew the location of the key to the Midwest. Southwestern Pennsylvania, where the Monongahela and Allegheny Rivers flow together to form the west-flowing Ohio. The vicinity of present-day Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania was about to be soaked with blood.

Monuments to the battle for the Midwest lie all along the National Road (present-day Route 40) between Uniontown and Farmington. If you want to see the important sites in chronological order, it’s best to see them travelling southeast from Pittsburgh on Route 40. Traveling in that direction, your first stop should be Jumonville Glen. This is where a young lieutenant colonel in the British colonial militia tipped the tense three-power balance into out-and-out war. His name was George Washington.

Jumonville Glen

On April 18, 1754, a British crew building a small fort at the site of present-day Pittsburgh was driven off by a larger French force. Lieutenant Governor Dinwiddie sent Washington from Virginia to Pittsburgh with a small contingent of troops to protect the site. British and French accounts differ about how the skirmish of May 28, 1854 began.

We do know for sure that Washington’s forces ambushed the French who were camped at Jumonville Glen, about forty miles southeast of Pittsburgh. In the brief skirmish, Washington’s troops killed the leader of the French forces, Sir Joseph Coulon de Villiers de Jumonville.

The future Father of our Country won that battle – sort of. Imprecise accounts indicate that as many as a dozen Frenchmen were killed and thirty taken prisoner, against only one Virginian killed and a handful wounded. But Washington was forced to withdraw, and he had not heard the last of the Villiers family.

The short, wooded walk from the parking area to Jumonville Glen is very pretty, even in the early spring when the trees are still bare. Bright-green moss lines the path, and when you reach the overlook it is very easy to see how Washington could have taken the French by surprise here.

Fort Necessity

Driving southeast on Route 40, the next monument is Braddock’s Grave (see below). But, if you want to see the sights chronologically, your next stop should be Fort Necessity.

While Washington was skirmishing with Jumonville’s troops, a larger force of the French kept busy replacing the fort that the evicted British had started. They called their new fort Fort Duquesne. From there Louis Coulon de Villiers – Sir Jumonville’s brother – led six hundred troops southeast to avenge his brother’s death.

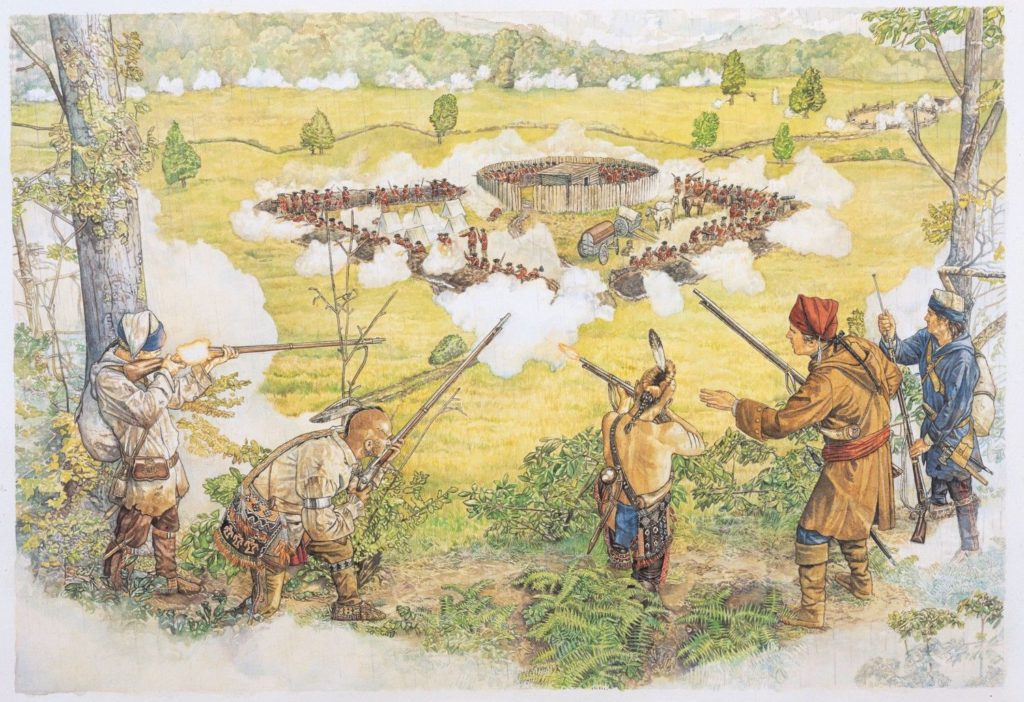

Washington expected the French to strike back and he made preparations. But he didn’t do a great job. He ordered his troops to rapidly erect a defensive fort at a site called Great Meadows. The location of the fort was a dream come true for the attacking French. It was flat and open, surrounded by trees that provided cover for attackers.

The ground was also swampy, and, as it happened, the coming battle would be fought in a driving rain. By the time Villiers offered surrender negotiations, thirty of Washington’s men had died in the flooded trenches, and seventy more were wounded.

Because he wasn’t sure when the British might be sending reinforcements, Villiers was surprisingly generous in his terms. The remaining Virginians, including Washington, were permitted to return to Virginia. But the light was poor, and the surrender document was written in French and poorly translated to Washington. So, he was unaware that he had just signed an admission to having assassinated Sir Jumonville.

Washington’s troops abandoned the fort on July 4, 1854.

The French had won – for the moment.

Fort Necessity National Battlefield Park

The national park at Fort Necessity has vastly improved since our first visit there. When we first visited in 1984, the park consisted of a reconstruction of the fort and a few signboards. Since then, the National Park Service has constructed a large new museum building with an ample parking lot, a movie theater, a fort-themed outdoor playground for children, and a gift shop. Excellent displays describe the history of the National Road and the fort. The grounds of the park also include Mount Washington Tavern. From the museum building, it is an easy walk to the fort reconstruction and a rather more strenuous walk to the nearby tavern (see below). You can also reach the tavern directly from Route 40. The grounds are lovely, dominated by stately pines, and knit together by well-shaded paths.

Despite its location just a few hundred feet from Route 40, the site of the fort was very hushed when we visited. It felt almost haunted to me in the stillness. I felt like if I stepped off the path onto the grass, I would step back in time and face the fort as it looked on that dismal July day in 1754, smell the wet gunpowder, and hear the cries of the wounded.

During the Depression, the Civilian Conservation Corps made some improvements to the Fort Necessity site. They built an especially handsome, sturdy bridge, which still stands.

Mount Washington Tavern

The tavern standing on the grounds of Fort Necessity National Battlefield dates to the heyday of the National Road. Built in the 1830s, it served travelers on the Good Intent stagecoach line. It was closed when we visited, but is normally open May – October from 10 a.m. until 4 p.m.

The Braddock Expedition

Backtracking northwest a little on Route 40, we come to the last chronological stop on our tour of the French & Indian War section of the National Road.

The battles at Jumonville Glen and Fort Necessity triggered the world’s first true world war. Western Pennsylvania was the starting point and epicenter of the nine-year conflagration known as the Seven Years War or the French & Indian War. But the war ultimately pulled in Prussia, Spain, Austria and other allies of both the French and the British.

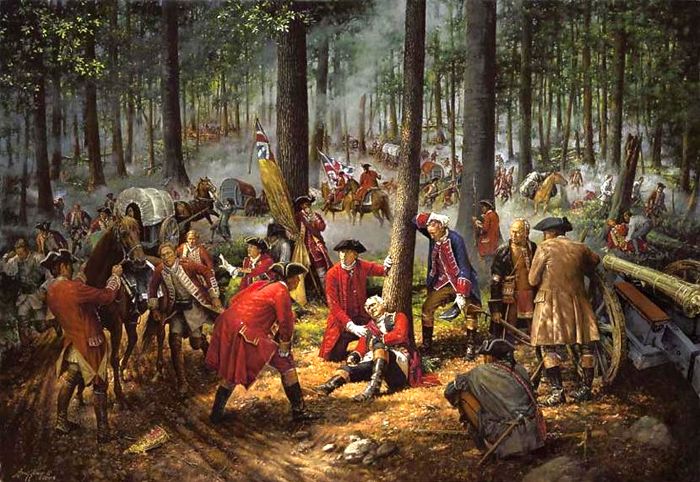

In the summer of 1755, early in the war, the British made another attempt to capture the all-important site of present-day Pittsburgh. General Edward Braddock set out from Cumberland, Maryland, with 2100 troops. How do you move that many men, along with their cannons, provisions and other equipment, through a heavily forested Appalachian wilderness? You build a 110-mile road, of course. And the road that you build becomes part of the route of the National Road six decades later.

The Braddock expedition included such future luminaries as Daniel Boone, Horatio Gates, and the 23-year-old bumbler who started the whole mess – none other than Lt. Col. George Washington. The presence of so many soon-to-be-famous men didn’t help Braddock much, though.

On July 9. 1755, soon after they had crossed the Monongahela about ten miles south of Pittsburgh, Braddock’s force was surprised by a much smaller force of French and their Indian allies. The terrain favored the French and Indians. After several hours of combat, Braddock was shot off his horse and killed, and the British began to withdraw. Only firm action by Washington prevented the withdrawal from collapsing into panic.

British victory at the forks of the Ohio would have to wait for the Forbes expedition, three years later.

Braddock’s Grave

The British originally buried Braddock on the road they had so laboriously built. In 1804, workers repairing the road discovered the body. They reburied it on a rise above the road, where it remains today under a granite monument.

A stop at the very-visible monument also gave us the opportunity to see a couple of hidden gems nearby: the original Braddock gravesite and some preserved remains of Braddock’s original road – mere feet from today’s Route 40.

Coda

In 1771, George Washington bought the land on which Fort Necessity had stood. He saw that the grounds lay along what would eventually be a well-travelled route west, and thought it would be a good investment. He visited the property in 1784, but sold it before his death in 1799.

The British won the Seven Year’s War and gained an empire. Ironically, their empire nearly bankrupted them just a couple of decades later, and it has since faded into history like all empires.

But the road that Braddock and his men started has survived, first as the National Road and now as Route 40. A traveler named Aldara Welby, quoted on one of the museum signboards, said it best in 1819. “The National Road is a work truly worthy of a great nation, both in its idea and construction.”

Next Up: I will be on vacation in early April, so Polly Hall will be my guest blogger. Polly is the author of The Taxidermist’s Lover, the most unique and imaginative book I’ve read so far this year.

And, finally, just for fun, here’s a picture of me on our first visit to Fort Necessity, in March of 1984. I was 8 months’ pregnant!

Sources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seven_Years%27_War

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Braddock_Expedition

Vivian, Cassandra; The National Road in Pennsylvania; Arcadia Publishing, Charleston, SC, 2003.

Also: the Pittsburgh Public School System. When I was student in the 1960s and 1970s, every Pittsburgh school child was taught this history and it is as familiar to me as a family story. I only needed my sources for exact names and dates.