Jane Grey Swisshelm held several jobs in her lifetime. Her father died when she was only 11 years old and her family was plunged into poverty. Jane had to produce paintings on velvet for sale as her contribution to the family’s income. She was at various times a writer, a newspaper publisher, a corset-maker, a quartermaster’s clerk, a street commissioner and a nurse. She was also a teacher in a one-room schoolhouse.

Wilkinsburg didn’t open its first public school until 1840. Before that time, there were private schools in the area of varying size and quality, including Edgeworth School, the ladies’ academy that Jane attended for a couple of years in her early teens. Following her education at Edgeworth, Jane opened a school of her own in her mother’s home in Wilkinsburg in 1830 – at the age of 15!

Jane bragged of being the first schoolmistress in Western Pennsylvania to teach without flogging. She taught seven hours a day Monday through Friday, plus Bible school on Saturday morning, for $2.50 per term per pupil. That would be about $67 in today’s dollars. Quite a bargain!

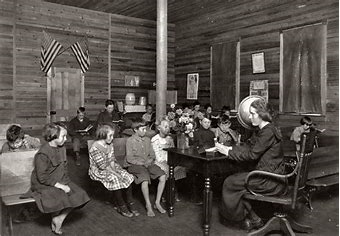

Jane probably taught students of all ages. Younger students would have sat in front, older in back. I’ve found no record of what she taught, but it most likely followed the general educational rubric of the one-room schoolhouse of the era.

A Typical Day in a 19th-century Schoolhouse

The students’ day usually started with the Lord’s Prayer. The first lesson of the day was in reading. Memorization was important in those time when books were in short supply and computers non-existent. Part of the reading lesson would include each child reciting a speech or poem from memory. After a privy break and perhaps a short recess, arithmetic and penmanship would be taught. Students practiced penmanship by writing their name, the date and a maxim or two in a copybook. The class might then discuss the moral meaning of the maxim.

Lunch and recess followed penmanship. After recess, children helped carry more firewood and water into the schoolhouse.

The teacher instructed her students in grammar and spelling in the early afternoon, followed by history. After another privy break, the class read and discussed a moralistic story. This was meant to both build character and develop elocution skills. The last class of the day was geography.

Behavioral Expectations

At dismissal time, children assigned for that day helped to tidy up the classroom. Chores for the next day were assigned at this time as well. Students who had misbehaved might have to stay late to sweep the floors and wash the tin drinking cup. Oher common punishments included whipping with a rod or ruler on the palms or buttocks, or spanking with a hickory stick. Since Jane was opposed to these physical punishments, she more likely stood her naughty students in a corner, or sat them on a stool wearing a dunce cap. She may also have had them memorize or copy long passages with moral messages, or write sentences over and over, while the other children were outdoors enjoying recess.

19th century parents and teachers placed a high value on good manners in children. “Making your manners” meant curtsying for a girl and bowing or nodding for a boy. An apple or some picked wildflowers was a kind way to make one’s manners to the teacher.

Jane as a Teacher

As I do my research, I find Jane to be a study in contrasts. She was certainly self-righteous; hence, the title of my book. She could be stubborn, demanding and unreasonable. But she was passionate about doing good, and she was very dainty and feminine in appearance when she was young. What would she have been like as a teacher? She describes herself as being so successful at non-corporeal discipline that “boys, ungovernable at home, were altogether tractable.” Were they charmed by her femininity? Or intimidated by her steely righteousness? I’d say it’s a toss-up. She is a complex character. I’m figuring her out as I write.

Sources

Half a Century – Jane Grey Swisshelm, 1880

http://www.heritageall.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/Americas-One-Room-Schools-of-the-1890s.pdf